When the levees broke, submerging much of New Orleans under seven feet of brackish floodwater in the summer of 2005, Darresha George was seven months pregnant. She sought refuge on a narrow bridge overlooking the city, where she remained, without food or water, for two days until she was rescued by a military helicopter. Buses would shuttle her and thousands of other New Orleanians to Texas, where she has lived ever since, eventually settling in the town of Mont Belvieu, about thirty miles east of Houston.

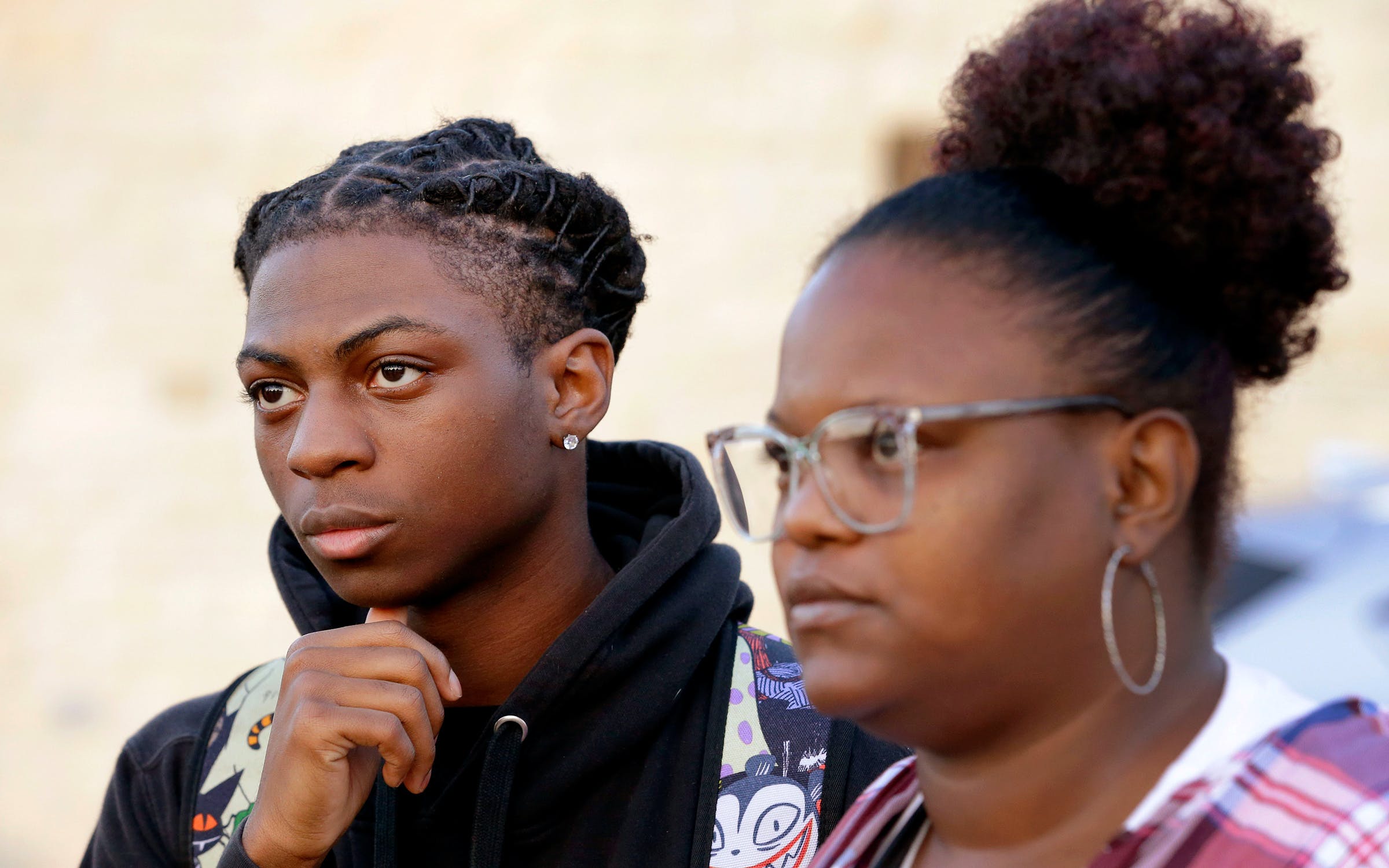

The baby she was carrying when she evacuated is now eighteen years old and at the center of a controversy that has garnered national attention after officials at Barbers Hill High School suspended the teenager for violating the district’s strict dress code by refusing to cut his locs, which he wears atop his head in a common style known as a barrel roll.

In August, at the beginning of the school year, Darryl George was forced into in-school suspension for having hair that was not earlobe length or shorter, as required for all male students. In suspension, Darryl was deprived of hot lunches and forced to sit on a stool for eight hours a day doing schoolwork without teacher instruction, his family says. But this month, because of his continued refusal to alter his appearance, the high school junior was removed from school entirely and placed in an alternative, disciplinary education program, where he spends his days in a classroom with students from various grade levels, according to his family. Though he’s been isolated from his classmates and teachers, the soft-spoken teenager appears calm and resolute in person, despite being treated, he says, “like someone in jail.”

Last month, Darresha and her Houston attorney, Allie Booker, filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against Governor Greg Abbott and Attorney General Ken Paxton for failing to enforce a new law barring race-based hair discrimination, as well as a formal complaint with the Texas Education Agency alleging that Darryl was being harassed by school officials. When her son’s in-school suspension began, Darresha thought the issue would be resolved within a few days. More than two months later, it drags on. “This is worse than Katrina,” she said, holding back tears during a recent interview. “When Katrina hit, we knew it would eventually be over and there was a light at the end of the tunnel. This time around, it’s been months and this storm doesn’t seem like it’s ever going to end.”

A close-knit family that never longed for the spotlight, the Georges say they never imagined they’d be in a legal fight with a school district. They say they’re refusing to back down because their hair reflects their heritage and, at its core, is an expression of strength, courage, and freedom. The fact that Darryl’s locs are pinned to the top of his head, they say, is further evidence that his hair doesn’t violate the district’s dress code.

As the legal battle drags on, Darresha is consumed with worry about her son’s well-being. Without instruction from the appropriate teachers, she fears that he is falling behind his classmates, putting his graduation in jeopardy. She also worries about his mental health. Like so many parents raising Black sons and daughters in small-town America, she knew it was only a matter of time before her child was forced to confront racism. But she didn’t expect that racism to come from an institution that was supposed to support him. “I have to see the hurt in my son’s eyes and the fear that he’s experiencing every day,” she said, prompting Darryl to put his arm around his mother’s shoulder, pulling her close as she began to cry. “I try not to show how much it’s hurting me because I need to stay strong for my family. But for a mother, knowing your child is the victim of racism every single day and he’s in pain in a place where he’s supposed to feel safe—that’s torture.”

This school year was supposed to be different. In 2020, school officials at Barbers Hill suspended two other Black male students—De’Andre Arnold and Kaden Bradford—for refusing to cut their dreadlocks, drawing widespread condemnation from athletes and politicians around the country. The school district’s policy, which was eventually overturned by a federal district court in Houston that same year, spurred the Texas Legislature to pass of the CROWN Act in May. The law bans employers and schools from discriminating against individuals based on their natural hair texture or protective hairstyles such as braids, locs, and twists. Advocates hailed the bill’s passage as a step forward in uprooting systemic racism and protecting cultural diversity across Texas. But the law does not mention hair length.

“Barbers Hill, they’re very strong-willed,” D’Andre Arnold told KHOU last month when asked about Darryl. “They will do what they want to do, regardless of what anybody tells them, whether it be the CROWN Act, whether it be me, whether it be anybody.”

Tehia Starker Glass, a professor of educational psychology and elementary education at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, told CNN in 2020 that dress codes like the one implemented by BHISD have nothing to do with hygiene and behavior. Instead, she said, they are a way of requiring that Black students conform to white expectations. “They already envisioned what the ideal child should look like in school, and they wrote the rules based on that,” Glass said.

David Bloom, a spokesman for the Barbers Hill school district, said the dress code has nothing to do with race and is “not in conflict” with the CROWN Act because it’s focused on hair length, not the nature of the hairstyle. Most hair-code violations, Bloom said, have come from white students. In 2020, however, a lawyer at the Juvenile and Children’s Advocacy Project of Texas reviewed old Barbers Hill yearbooks and discovered multiple examples of long-haired white male students, according to the Texas Tribune.

Reached by email, Greg Poole, the superintendent of Barbers Hill ISD, said the BHISD dress code is modeled on the idea of replicating the attributes of a team, as part of an effort to unify students distracted by iPhones. “The student in question moved here from a neighboring district that allows him to wear his hair any way he wishes,” Poole wrote. “Shortly after he moved here we were contacted by a lawyer. You can deduce the rest.”

Candice Matthews, a civil rights activist who is serving as a spokesperson for the George family, called the insinuation that the family moved to the district seeking a legal fight a “typical racist response.” “The George family moved for personal reasons, as is their right as Americans,” she said.

In August, Darresha George submitted to the school a request for a religious exemption from the hair code, writing that men in her family wear locs to express their connection to their ancestry, which, in turn, maintains their relationship with a “Higher power.” The request was provided to Texas Monthly by Matthews, as was an email in which Lance Murphy, the principal of Barbers Hill High School, rejected Darresha’s request. In the email, Murphy wrote that Darresha had failed to provide evidence of any religious ceremony relating to the length of Darryl’s hair. “Additionally,” Murphy wrote, “you indicated that there is not a religious entity nor religious leader guiding your son’s study or practice other than his step-father who you said is not an ordained minister.”

Matthews said school officials—particularly white ones—have no right or ability to define a Black student’s spiritual beliefs or make judgments about their relationship with their ancestry. “Black culture is for Black people to define, not white school officials engaging in discrimination,” she said.

Asked what qualifies Murphy, who is white, to make judgments about ethnic hairstyles and their connection to someone’s spiritual life, a tradition that has been documented in cultures around the world for thousands of years, Poole said he was “appalled” by “such a racist question.” Poole referred to Murphy as “an exceptional leader of one of the highest-achieving schools in the state.” “We do not have an exception for not wanting to follow the rules,” he wrote. “We are currently in a federal lawsuit to determine if our policy is legal and we have every reason to believe the right of our community to set appropriate standards will be upheld.”

Even if the George family prevails, serious damage has already been done, according to Matthews. Darresha has long struggled with anxiety and suffers from epilepsy, which can result in her experiencing sudden, violent seizures. As is the case with many epileptics, Darresha’s seizures are triggered by stress, which she has spent years learning to manage. But in recent weeks, she says, she’s been inundated by a new wave of seizures that has left her feeling like she’s losing control of her body.

Several days after our interview, I learned that Darresha would not be able to respond to follow-up questions. She had been hospitalized, and Matthews had assumed power of attorney. Days earlier, when I spoke with Darresha in her home, she was overcome with frustration. “This is a kid who wants to go to school, who wants to learn, wants to do something with his life, and y’all [school officials] are pushing him back,” she said. “Y’all are telling him that, because of the way he looks and the way he wears his hair, he can’t be somebody in this world. For what? What is the point of all this?”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

You must be logged in to post a comment Login