Editor’s Note: This feature is part of CNN Style’s series Hyphenated, which explores the complex issue of identity among minorities in the United States.

CNN —

From the outside looking in, Prachi Gupta’s family was the epitome of the American Dream.

Her father was a doctor, her mother was a caring homemaker and she and her brother Yush were high achievers. They had settled into a grand, five-bedroom home in the Philadelphia suburbs, and never wanted for material comforts. This success, Gupta was raised to believe, was a testament to their hard work and Indian cultural values.

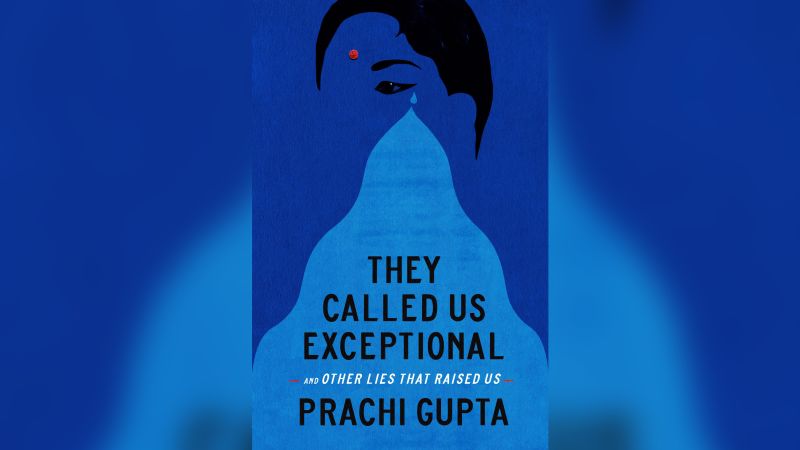

Beneath the surface, a different narrative was unfolding, she writes in her new memoir “They Called Us Exceptional.” Her father’s temper and strict rules created a turbulent environment at home, and Gupta struggled to reconcile her family’s dysfunction with the picture-perfect image they presented to the world.

“If you believe that success and achievement is part of your core identity and who you are, any struggle you have, any trauma you have, any hardships you face then are internalized as personal failure,” she said in a recent Zoom interview. “It forces us to hide anything that’s imperfect.”

As Gupta tells it, each member of her household responded to the turmoil at home differently. Her mother chose largely to tolerate her husband’s manipulative behavior despite his mistreatment of her. Gupta came to reject the toxic dynamics she had once accepted, estranging her from her family. Her brother learned to bury his emotions, leading him down a path that she said ultimately killed him.

In a deeply vulnerable book that combines personal narrative, history and cultural reporting, Gupta examines how the weight of the “model minority” stereotype led her family to unravel.

CNN spoke to Gupta about the tragedy that prompted the book, why she wrote it as a letter to her mother and whether the American dream was ever real.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What prompted you to write this book?

In 2017, my brother Yush died. We had been estranged for two years at the time but before our estrangement, we had been very, very close. He’s 18 months younger than me and we were best friends for most of my life. The way that he died (a blood clot after cosmetic limb-lengthening surgery) and the suddenness of his death really prompted me on this journey. I had to understand who he had become and why he made the decisions that he made that led him down this path.

Part of the reason that we were estranged was because I’m a very vocal feminist, and he began to espouse men’s rights views. When he died, I reported on who he had become and how he had died in an essay called “Stories About My Brother,” which ran on Jezebel in 2019.

When that essay ran, I heard from so many people in the aftermath. I heard from immigrant moms who said they had no idea what their kids might be going through and that they were going to start talking to them about their mental health. I heard from sisters who had similarly complicated relationships with their brothers and said this helped them understand their brothers better. I heard from Asian American men who said they were going down a similar path as my brother was and that this essay convinced them to think differently and seek help. Men from all races (told me) they had been struggling with depression and had never been able to admit it before.

When I realized how many people were struggling with such similar issues but felt alone, I felt that it was important to tell my full story. There was so much more to share about how the culture that we live in trains us to divest from ourselves and our communities by focusing on success and achievement.

I felt like if I had had this story when I was younger, if somebody had been able to piece this together for me and my brother, maybe we could have still had a close relationship. And maybe he wouldn’t have made the decisions that he made that led to his death.

Why do you think your and your brother’s paths diverged so starkly in adulthood?

We grew up in the same household, but we had really different experiences.

We had very traditional gender roles in my house. That became a divide between me and my brother, because I grew up seeing this injustice and how I was being treated differently because I was a girl. And I think he absorbed these messages about masculinity, about what it is to be a man. He learned that he couldn’t express emotion. He learned that it wasn’t okay to talk about your feelings and that there was this expectation to provide.

These different expectations on each of us, combined with the dysfunctional dynamic of my household, really began to push us apart as we got older. I began to push against the family system and wonder why things were the way they were, whereas he leaned into that traditional role. That became the source of friction between us, and we could never reconcile that.

You documented many of the painful events detailed in the book as they were happening. Did you know at the time that you wanted to write a book about your family?

There was always some part of me that thought this was important to document.

Writing was the way in which I made sense of the world. I grew up in a household that was very volatile, and reality could slip in a second. My dad would change the facts — suddenly, I’m being told that things didn’t happen, but I remember that they happened. I was always questioning my sanity, and writing was a way to help me remember. It always felt vital to my survival to write all of this down. But I never planned to write a memoir or write about this in a personal way. I wanted to use those observations to one day write fiction.

After Yush died, I didn’t want to turn him into a hypothetical. I wanted to honor his memory and use that to talk about the real harms that these ideas caused. We talk about them in the abstract, but they took my brother’s life. These pressures are real, and they do real damage on our bodies, on our lives, on our relationships. And I want people to know that.

In the book, you don’t often use the terms “abuse” or “domestic violence” to describe what was happening in your household. Was that intentional?

Yes, it was intentional. I’ve drawn a lot of empowerment from naming these dynamics as abuse, as toxic, because it helped me escape them. But at the same time, they can sound so black and white and cut and dry. I wanted to show that being in the throes of this is not cut and dry. It’s not black and white. When a person that you love deeply also hurts you deeply, it’s a very disorienting experience, and it’s not so easy to just name it “abuse” and walk away.

I also wanted to show what it feels like. When we use the word abuse or domestic violence, everyone has a different image of what that is. A lot of people focus on physical abuse as abuse, but there’s a whole spectrum of psychological and emotional abuse. We don’t really have a great way of talking about that and the effects of that.

The book is written as a letter to your mother. Why did you choose to address her?

After Yush died, I wanted to reconnect with my parents more than anything. I wanted to keep the memory of Yush alive through our relationship. But this was really hard to do.

I was thinking about mortality a lot after he died and I didn’t want something to happen to my mom or me without her knowing who I really am on my terms — without having a chance to explain to her why our relationship remains so distant and why that has nothing to do with how much I love her.

I didn’t know how to tell her that, so I felt like I had to write to her.

Do you know if she’s read the book?

I don’t know. I did write (my parents) a letter before I sent it. But I don’t know if she has read it or not.

I agonized a lot over whether to do this, but ultimately I decided that I had to. After my brother died, I had to find meaning in his death. I had to use that suffering to find a way to both heal myself and help other people heal. I don’t think we’re the only family in America who’s struggling with these issues.

I felt like I had to use my story to help warn other people about what can happen when we prioritize achievement — as we’re taught to and as a lot of immigrants especially are pressured into doing — and what the cost of that personally can be.

Your book is titled “They Called Us Exceptional.” Who is “they” in that sentence?

“They” refers to White America, and the exceptional part is a reference to the “model minority” myth.

There can also be a reading of it where “they” is our own (Asian American) communities and how many of us self-identify with that myth as a survival strategy, as a means to assimilate and belong.

How did the “model minority” stereotype affect your own family?

Growing up Indian American, I didn’t know Asian American history. We didn’t learn that in schools, so I didn’t really understand where I fit into America’s racial hierarchy.

What I did know are the stereotypes — and the immediate world around me confirmed all of those. I saw this story as if it were my identity, because I didn’t really see an alternative. I didn’t understand the historical and political forces that shaped why my community looked the way it did. My dad is a doctor. A lot of our immediate family and friends who were Indian were doctors and engineers, and they all came from that professional class. I didn’t understand that immigration history and laws really shaped a big part of that.

I just identified with this perception of who we were as something innate. It was limiting and flattening belief, especially because I didn’t always fit into that. I wanted to be an artist and a writer. I was a runner. In my household, though, there was so much pressure to conform to these expectations.

You also write about the stigma around mental illness in Indian American communities. Where does that come from?

We’re taught growing up that success solves all your problems. So if you work hard and you achieve, you won’t have mental health issues. I thought that all these rules I followed were to create stability, happiness, unity. I actually saw success as an antidote to suffering and an antidote to mental health issues. Now I know that that’s not true.

In fact, the focus on external validation and success in America causes a lot of mental health issues because we’re so focused on what others think of us and how others value us rather than learning how to develop our own sense of inner peace. We lose the ability to be vulnerable with each other when we’re focusing on how to project the right image to each other instead.

Traditionally, we’re not really supposed to be seen this way. To be seen this way is to incur violence and to be surveilled as brown people in America. We also have a strong colonial history of mental health being used to surveil, dominate and control colonized people. That’s what the British did in South Asia. They would round up any South Asian who didn’t adhere to Victorian social norms and put them in what they called “lunatic asylums.” They turned these asylums into for-profit labor camps and called it therapy.

So there’s also a lot of skepticism and wariness around mental health. And the mental health system here often doesn’t have the cultural competency to address issues like racism and cultural confusion that so many children of immigrants deal with.

Do you still believe in the American Dream?

The American Dream is really only accessible for a small number of people. It’s not accessible for most people, especially most people of color. While my family did succeed, the part of the American Dream that we forget when we talk about it is that (we’re taught) all of this stuff leads to happiness. We’re taught that if you work hard, you will achieve. And if you achieve and you succeed, you will be happy. You can do all of those things and still be really unhappy.

How many people can relate to getting that dream job or getting the grades that they want or getting into the right school, and then they get there and they’re miserable? We are taught to equate success with happiness in this country. But the thing is that success and achievement is so often more focused on productivity and labor, and it’s not really about our mental health or our wellbeing or our relationships or our ability to be our true, authentic selves.

What kind of behaviors do we associate with success? Does that mean that person is kind or good or compassionate or loving or caring? We have a lot of ideas wrapped in the idea of success that are not necessarily true. And we make a lot of judgments on people, both good and bad, just based on how much they’ve achieved or what status they have in society.

I hope that this book can help people re-examine some of those myths, and also help take off some of the pressure to aspire to do these things.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login