Almost half of books challenged at school are returned to shelves, but titles with LGBTQ characters, themes and stories are most likely to be banned, according to a Washington Post analysis of nearly 900 book objections nationwide.

School officials sent 49 percent of challenged titles back to shelves, The Post found, a discovery some interviewed for this story hailed as proof the national alarm over book challenges has been overblown – although librarians warned of a severe burden on employees forced to spend months defending titles. The next most-common outcome, in 17 percent of challenges, was for a book to be placed under some form of restriction. Libraries might require parental permission or limit the youngest students from checking out a given title.

And school officials permanently removed 16 percent of challenged books, making that the third-most-common outcome. In the remaining cases, the books were either still under review as of late 2023, were never reviewed by the district or were unavailable before the challenge.

The Post requested the results of all book challenges filed in the 2021-2022 school year from more than 100 school districts, which The Post had previously identified as fielding formal objections during that time. In total, officials in those districts shared the outcomes of 872 challenges to 444 books across 29 states.

The Post analyzed the types of books challenged to determine what titles were most likely to be removed, restricted or retained. Books about lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer lives were 30 percent more likely to be yanked, The Post found, compared with all targeted books. By contrast, books by and about people of color, or those about race and racism, were 20 percent more likely to be kept available compared with all targeted books.

Amid a national debate over what to teach about race, sex and gender, book challenges surged to historic highs in 2021 and 2022, according to the American Library Association, which has tracked such objections for more than two decades. But little has been done to analyze the effect of these challenges — although a 2023 report from the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute found that 74 percent of books PEN America tracked as “banned” in 2021-2022 remain available, per public schools’ online library catalogues. (PEN America, a free-speech advocacy group, acknowledges that it defines a ban as any action taken against a book, ranging from removal to diminished access.)

There is no reliable national data on the outcomes of challenges to titles at public libraries, said Shannon Oltmann, an associate professor of library science at the University of Kentucky. But, Oltmann said, she and a colleague have just received a federal grant to investigate that question. She called the rate of books placed back on school shelves “a really promising statistic.”

“That is most welcome news to hear,” she said, although she cautioned that book restrictions can function as bans. And she lamented the finding about LGBTQ books: “We know from research that reading about people different from themselves helps youth develop empathy, compassion and broader understanding.”

Others hailed The Post’s findings as evidence that school districts are appropriately taking into account parent, staff or student discomfort with books offered to children in libraries or classrooms.

In interviews, librarians across the country said they were heartened by the rate of returns — but cautioned that the success can come at a high cost. Defending books from challenges is equivalent to a “second full-time job,” said Martha Hickson, a New Jersey school librarian who fought attempts to ban five LGBTQ books in the 2021-2022 school year.

Hickson, 64, worked evenings and weekends to coordinate a defense of the titles, recruiting the help of community members, authors and free-speech advocacy groups, she said. She also faced down allegations that she was a pornographer and a pedophile, shouted by parents at school board meetings and written into the book challenges, which named her personally.

Although her school board ultimately voted to retain the five books, the experience damaged Hickson. She had a mental, physical and emotional breakdown in fall of 2021 and had to take a month off work. She is “barely going at this point” and worries for other librarians throughout America, she said.

Books returned, books restricted

In February 2022, the superintendent of Pennsylvania’s Warwick School District wrote a six-page letter to a parent explaining the district’s deliberations over “All American Boys,” a novel about a Black teenage boy and a white teenage boy who witness an instance of police brutality. The parent had alleged that the book was offensive and would strip children of their innocence.

Superintendent April Hershey wrote in her letter, obtained by The Post, that school officials sought the perspectives of teachers and students as they weighed the title. Educators reported that the book spurred “interaction, engagement and discussion,” and a student said she related to its characters, Hershey wrote.

Hershey wrote that the parent could opt their child out of reading the text – but that “your objection to this material or any materials ends with your own child(ren). Other families have the right and responsibility to determine what is acceptable for their own child(ren). . . . The book ‘All American Boys’ will remain.”

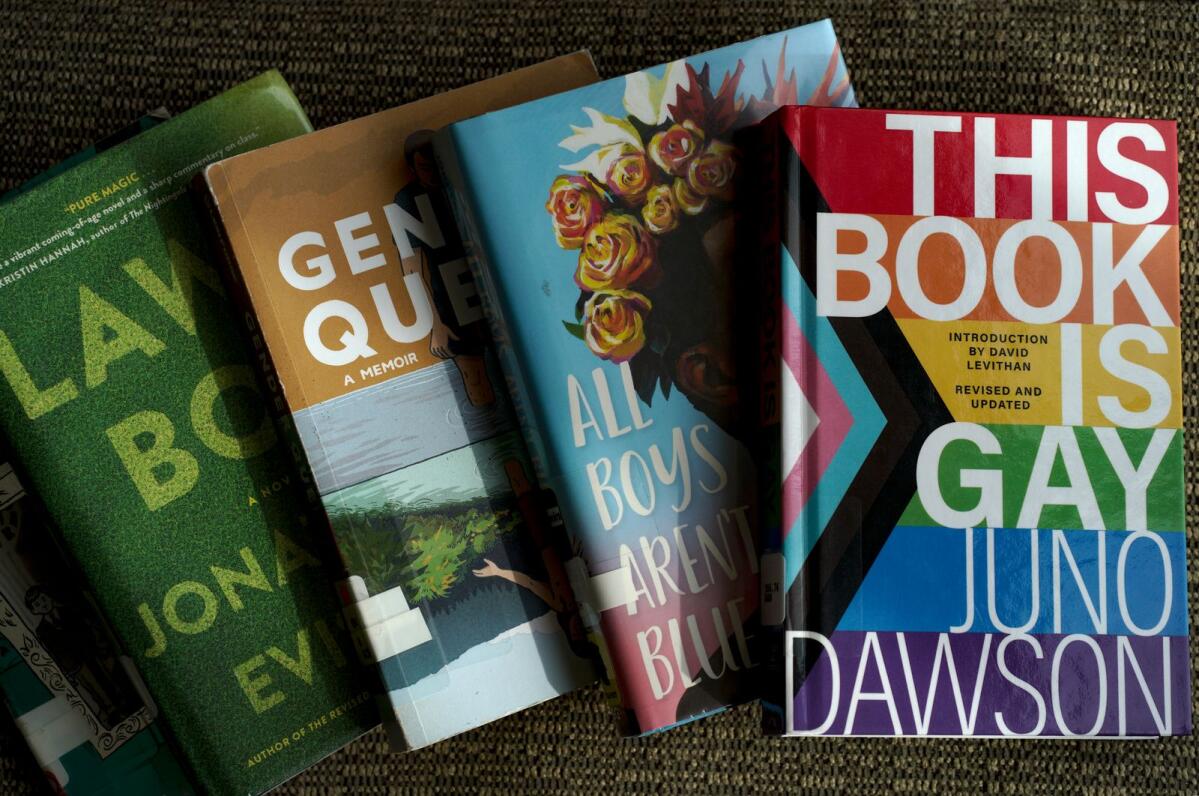

In many cases of book returns studied by The Post, administrators conducted thorough reviews. The reviews often involved weeks of discussion by committees of librarians, teachers, parents and sometimes students. The panels produced detailed arguments for keeping the titles. A committee in Iowa’s Urbandale Community School District, for instance, decided to retain “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” which chronicles growing up Black and queer in the South, in part because it “could create empathy for others who are different.”

Requiring parental sign-off is one of the two most common forms of book restriction, The Post found. The most common is limiting access to high-schoolers: That was the case in 46 percent of the 151 book restriction cases The Post tracked. Twenty-six percent of restricted titles were made available only with the permission of parents. Additionally, 9 percent were limited to middle-schoolers and above.

These types of restriction can function like bans, experts warned. Oltmann, the University of Kentucky library science professor, called age restrictions “a way of de facto removing access, because no middle-schooler is going to go to the high school library” to find a restricted book. She added that some students will not feel safe asking their parents for permission to read a restricted book.

What happens after a book is banned?

Of the 140 fully banned books in The Post’s analysis, 41 percent featured LGBTQ individuals or storylines. Books by and about people of color, or dealing with race and racism, made up 10 percent of banned books.

LGBTQ titles also made up a sizable percentage of books that were restricted but not banned: nearly one-third, or 28 percent. Books with authors or subjects of color made up 31 percent of restricted books. And LGBTQ books were 20 percent more likely to be unavailable before drawing a challenge. (The Post previously found that 43 percent of 2021-2022 school challenges targeted LGBTQ books, while 36 percent targeted books dealing with race.)

The overrepresentation of these books in challenges and removals means that LGBTQ students and students of color will suffer, said Sam Helmick, president of the Iowa Library Association.

“And all students will learn that ideas and speech are things to fear and avoid,” Helmick said.

The Post’s analysis of challenge outcomes fails to account for informal book removals, which do not stem from objections but which are also soaring, said Kathy Lester, a board member of the Michigan Association of School Librarians. The Post previously reported that school administrators nationwide are secretly yanking books before they can be challenged.

Lester said that, starting in the summer of 2022, she began hearing from librarians in dozens of districts about formal book challenges — and from dozens of librarians elsewhere about more insidious, surreptitious book culling.

“A similar number of people have been reporting some level of soft censorship from administrators telling them they cannot purchase certain materials,” she said, “or quietly pulling things from the shelves.”

What happens to books after they are banned varies. The Post asked every school district about the fate of eliminated titles, but the vast majority did not answer. One district in Iowa said books taken out of circulation are “stored in a secure location by the school librarian.” A Texas school division said banned books are “taken to our district’s warehouse.” A Wisconsin district reported that “copies were recycled.”

School librarians tasked with getting rid of unwanted titles said they will never forget it. Of hundreds contacted nationwide, only a handful agreed to speak, all on the condition of anonymity for fear of losing their jobs.

A school librarian in a Michigan district said an assistant superintendent told her last year to nix several books with LGBTQ themes. She pulled down one book from the shelf, placed it in her bag and carried it to the administrator’s office, where it remains. She had to ask a teacher to pry a second book, “The Magic Misfits” by Neil Patrick Harris, from the hands of a student busy reading it.

“I just felt so terrible,” the Michigan librarian said. “This student was enjoying it and now they’re going to question: What was in that book that isn’t appropriate?”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login