In the spring of 2018, Abena Marfo left her home in Garland and drove to the leafy campus of Southern Methodist University, a private school located in the upscale Dallas enclave of University Park. She was both nervous and excited to tour campus and meet professors who might be teaching her in the fall, when she would start at SMU as a freshman. But as she drove through campus, she saw the flash of police lights in her rearview mirror. The $180 ticket for failing to yield on a left turn stung, but what left her reeling was what the officer asked her:

What was she doing on campus? It felt like yet another “driving while Black” moment.

Though the incident didn’t stop her from attending SMU, it was a taste of her next two years. “That moment was my preview of what it was like to be Black at SMU,” Marfo said. “We’re seen as other. It’s made clear that we don’t belong and that some people feel like we’re intruding.”

Nonetheless, Marfo found safe harbor among a tight-knit community of Black students, especially those involved in the African Student Association, a cultural organization that empowers African students. Marfo is now president of the group. But she had been reluctant to publicly share her experiences until this spring, when the Black Lives Matter movement helped students at SMU find their voices. Within a week of George Floyd’s killing by police in Minneapolis, Black students and alumni began telling their stories under the hashtag #BlackAtSMU, part of a resurgence of racial-justice activism on the campus. Though the hashtag first circulated in 2015, it gained new currency in the spring as Marfo and dozens of other students and alumni came forward with accounts of their experiences at the private institution of just under 12,000 students, from being called racial slurs at fraternity parties to graduating without having been taught by a single Black professor.

The university has made strides in diversifying its student body; in 2019, minority students made up 29 percent of total enrollment, up from 26 percent in 2015, but that was almost entirely a result of growth in the number of Hispanic and Asian students. During that same time period, the Black share of undergraduates decreased slightly from 4.6 percent in 2015 to 4.4 percent in 2020. That share is roughly comparable with UT-Austin (5.1 percent), TCU (5.5 percent), and Texas A&M (3.3 percent).

Black students say they don’t fit into SMU’s “bubble,” a term they use to describe the feeling of being Black in a sea of affluence and whiteness. The SMU student body is unusually wealthy, even for a private institution. Nearly a quarter of the student body hails from families in the top 1 percent of income-earners—the third-highest among all private schools in the nation according to a 2017 study by a team of researchers. Only 3.3 percent of students come from families in the bottom income quintile. This casual affluence is reinforced by the campus’s location in University Park, one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in Texas. Marked by stately homes and winding, tree-lined streets, University Park is more than 90 percent white and has a median income of about $215,000. The “bubble,” Black students say, creates a safe space for privileged white students and an uncomfortable, sometimes hostile, environment for Black students, especially those from working-class backgrounds.

As the fall semester gets underway, students say #BlackAtSMU is central to their efforts to become more visible and to alert SMU’s administration to the university’s shortcomings. Many students say they finally overcame their reticence to speak out after President Gerald Turner issued a statement on May 30, during a period of the most intense BLM protest, that lamented the “continuing threat of racism” but also fretted over “the violence that often mars legitimate mass public protest.” Students quickly noted that the statement did not contain the word “Black.” Turner released a second statement on June 4 acknowledging that his original message did not sufficiently express his anger at another Black person’s death at the hands of police.

In the thread, students shared stories of feeling invisible and unwanted. They told stories of Black women being excluded from white sororities because they didn’t fit in with SMU culture, and of a makeshift “Make America Great Again” banner hanging from a fraternity house after the 2016 presidential election. Many students decried professors making insensitive remarks in class. Third-year law student Cole Davis said an adjunct professor, John Browning, compared himself to Dred Scott during the spring semester.

“He liked to start off class with a bunch of jokes,” Davis said. “He was like, ‘I almost feel like I’m Dred Scott: three-fifths of a full-time professor.’ I can’t remember what the topic of class was after that, but because I was so stunned by that I didn’t pay attention.” Davis didn’t confront the professor, but he mentioned the incident in an end-of-semester feedback survey. Browning, who is also a partner at Spencer Fane LLP in Dallas, disputed Davis’s account. Browning said he didn’t compare himself to Dred Scott, but instead was referencing the way adjunct professors aren’t treated the same way as full-time faculty under American Bar Association standards for law schools. “’How very Dred Scott of them’ was my exact statement,” he said.

Many Black alumni are now speaking out for the first time, something many were uncomfortable doing as students. Kaleb Mulugeta, for example, was the only Black man to graduate from the advertising program this May. He says he was on a scholarship and couldn’t risk confronting his peers or professors. “I didn’t want to seem like I was biting the hand that was feeding me,” he said. “It was a testament to what goes on and how Black students have to be silent about these issues until they’re encouraged by other people telling their stories.”

So, instead, he began keeping a journal of things that happened to him on campus, like when he was called “my nigga” by a white student at a fraternity party and a student responded, “sorry about Paul, he gets a little racist when he’s drunk.” Mulugeta is turning his journal into a book, which he’s calling The Token Black Boy Playbook, a user’s guide to how to survive as a Black man in all-white spaces. “I kind of just wrote everything down because I didn’t have the energy to fight this day in and day out,” Mulugeta said. “For me, part of that was just coping.”

But Mulugeta said he found meaningful connection with faculty. “I had immense support from two or three professors in my field,” he said. “Creative advertising is a really tight-knit community. I found my place with the professors that basically ensured, for the most part, that I would come out of SMU successful.”

Throughout the summer, Black prospective SMU students reached out to Mulugeta via social media for advice. “I would recommend SMU to other Black people with an asterisk,” he said.

The flourishing of #BlackAtSMU stories felt like a moment of reckoning, but many students are also well aware that their stories and demands are not new or unique. There were “I, Too, Am Harvard” in 2014, Concerned Student 1950 at the University of Missouri in 2015, and #NotAgainSU last year at Syracuse University, to name a few. “The link is that all of these spaces were built on white supremacy and the problems are systemic,” said Joy Melody Woods, a PhD student in the department of communication studies at UT-Austin’s Moody College of Communication and cofounder of #BlackInTheIvory, a campaign of self-described “Blackacademics” who call attention to racism in higher education. “What happens when people share their stories is that white people and non-Black people of color can no longer say these protests are just one-offs. These people are all telling the same stories.”

SMU is where Anga Sanders learned what it meant to be Black. The Marshall native entered the university in 1966, fourteen years after the first Black students were admitted. Before classes started her freshman year, students from a boys’ dorm asked the girls in Sanders’s dorm to join them on a picnic in a nearby park. Sanders was the only Black person in the group. As the students coupled off and mingled, Sanders was left alone. Nobody spoke to her or brought her into their group. For two hours, she sat in the park alone, unsure of how to get back to campus. “That was the moment that I realized that although I thought I was like everybody else, everybody else didn’t think I was like them,” Sanders said. “I lost my innocence that day.”

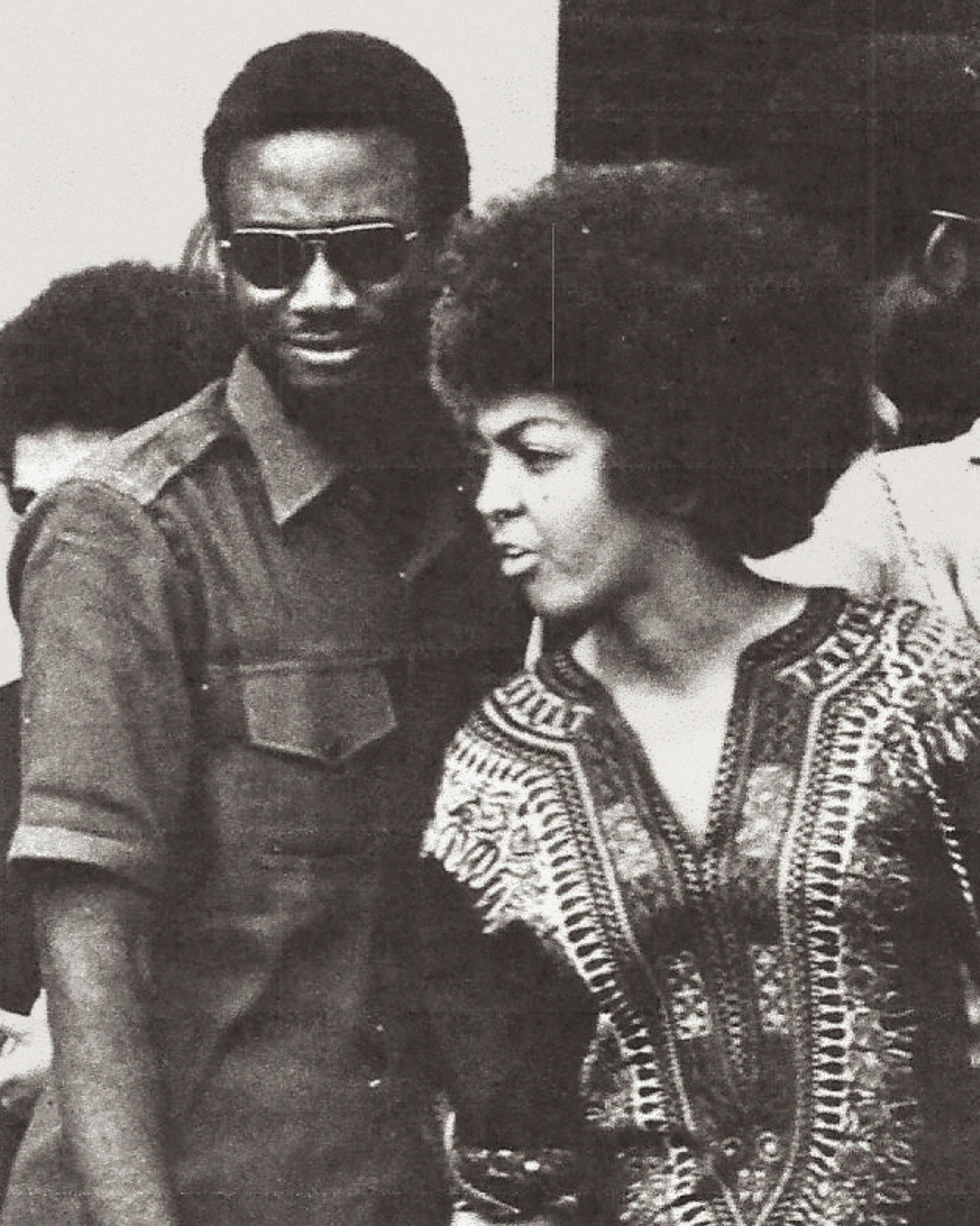

According to Sanders, there were 10 Black students on campus her freshman year. That number rose to 35 by her junior year, but Sanders said they felt isolated and had to create community to survive. Most were involved in the Black League of Afro-American and African College Students, an organization formed in the fall of 1968 that fought for racial equity on campus. “Our existence was one of benign neglect. They mostly didn’t bother us, and we didn’t bother them. But in 1969 we bothered them.”

In April of that year, Sanders and 32 Black students occupied SMU president Willis Tate’s office. The action had been building for some time. For months students had been combing through class syllabi, looking in vain for Black scholars. In classes, they saw no Black professors. And on campus, they couldn’t help but notice the scarcity of Black students. In Tate’s office, the activists presented a list of demands: targeted recruitment to increase the number of Black students to 500; the inclusion of Black scholars’ work in the school’s curriculum; better working conditions for Black staff; a gathering place designated for Black students; and hiring Black professors with the goal of making the Liberal Studies faculty 20 percent Black. Some of the demands were met: the students got a central gathering place on campus, called the BLAACS house, Black cafeteria workers’ wages were increased, and Black students were hired to help with recruitment.

Forty-six years later, in 2015, Black students referenced these demands as a new era of activism flourished under the #BlackAtSMU banner. That year, Black students led protests on campus after a culturally insensitive fraternity party flier invited partygoers to “bring out your bling, jerseys and inner thug.” Non-Black students used Yik Yak, an anonymous social media platform, to taunt Black students, post racist comments, and criticize pushback against the party flier. #BlackAtSMU became a rallying cry.

As #BlackAtSMU spread, the Association of Black Students drafted a list of demands—many of them echoing the 1969 manifesto—and met with Turner, who has been president of SMU since 1995. In response, Turner scheduled monthly meetings with an advisory board of Black student leaders and instituted a cultural intelligence initiative, known as CIQ@SMU, that guides all diversity and inclusion training at the university. Turner also created a Greek Life Diversity Task Force to review the diversity of fraternities and sororities and made a three-hour diversity course mandatory for all students.

“I felt like the onus was on us to educate administration on what was going on and also hold them accountable,” said D’Marquis Allen, president of the Association of Black Students from 2014 to 2016. “SMU counts on students graduating, because once you figure things out, it’s time for you to leave. President Turner has been here for twenty years but not much has changed. It can be demoralizing.”

Sure enough, five years later, students say not enough progress has been made. The changes sought by students in 2020 go well beyond sensitivity trainings and task forces. In demands presented to Turner in June, students called for each minority group to have a separate presidential advisory board, no fewer than one-third of first year seminar classes to be dedicated to cultural education, more on-campus Black mental health professionals, and the end of a student organization system that they say privileges large, community-wide events over events held by minority-led student groups. Students also requested a $7 million endowment for need-based scholarships for Black students and want the university to hold students and student-led organizations accountable for racially insensitive conduct in accordance with the Student Code of Conduct.

After meeting with student leaders Black faculty, staff, and alumni, Turner released a letter pledging a “commitment to action.” Turner also pledged to give each minority group its own advisory board and to do more to recruit Black students by using same-race recruiters starting in the fall. But he argues that rapid change is not easy. As an example, he points to the difficulty of increasing the percentage of Black professors from the current 4 percent to 10 percent, which would require hiring at least 44 new Black professors.

“Students want more Black professors, especially those that are tenured, on campus, and I understand this demand,” he said. “But the number of Black people receiving PhD’s has stayed the same over recent years. That makes the hiring pool small and our job more challenging.”

For Turner, the top priority is creating a “culture of civility” at SMU. “We have to make a blitz in the fall,” Turner told Texas Monthly. “There will be meetings in the first two weeks of starting on campus. This is not an issue that minority students must solve. It’s up to every member of this community to create this culture.”

Turner said that the university’s online bias reporting tool will serve as the primary method for measuring success in improving the campus culture. Created as a result of the 2015 #BlackAtSMU movement, the website allows students to alert administrators to harassment, threats, discrimination, intimidation, or assault and name the parties involved and the nature of the bias. “We review each case that is reported,” said Turner. “We need students to keep reporting incidents, so we can see if the number of cases goes down.”

In mid-August, Turner appointed Maria Dixon Hall, an associate professor of corporate communications, to the newly created position of chief diversity officer. Now that students are back on campus, Dixon Hall believes that the conversations and strategizing that took place over the summer will need to be translated into change that students and faculty can see. “Everyone knows that there is an expectation of action,” she said. “What makes it even easier is that I have a president who wants action, who expects action, and is not going to take anything less than action.”

In her new role, Dixon Hall is tasked with creating a new strategic plan for diversity, convening a newly formed committee made up of diversity officers from each college, and supervising a new position, university ombudsperson, who will confidentially counsel students, faculty, and staff who experience conflicts based on race, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and religion.

Student body president Molly Patrick, who is white, wants to bolster support for Black students by requiring cultural sensitivity training for members of the Student Senate and revising the Student Code of Conduct so it better reflects an intolerance for hate speech and racism on campus.

As they wait for Turner’s plan, Black students say they are trying to keep their spirits up as they begin a fall semester that will take place against the backdrop of the pandemic, a crucial election year, and the Black Lives Matter movement.

“Our fight isn’t over,” Marfo said. “We have to keep holding the administration accountable, so all of the Black students after us don’t face what we face. It’s bigger than us.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login