“Sometimes, it gets so hot down here,” Hattie McGill sang to hundreds of onlookers assembled before Waco City Hall. “It feels like my soul is on fire.” The recent Sunday afternoon ceremony had begun with a prayer and a haunting a cappella performance of McGill’s version of “Motherless Child,” the spiritual that originated among enslaved laborers in the American South.

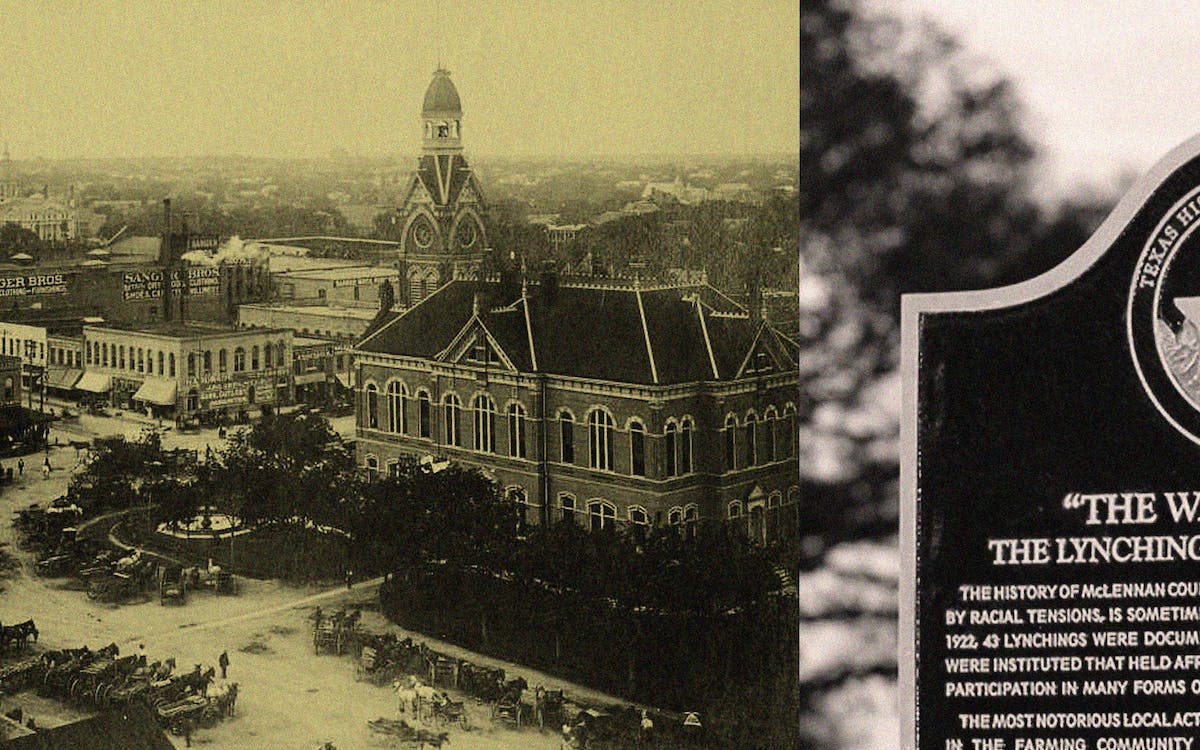

We had all gathered under a clear blue sky to witness the unveiling of a state historical marker commemorating a brutally racist incident. Many, like me, had been born and raised in Waco. Others had come from places as disparate as Houston and Wales. As the marker’s text noted, more than a century before, on these grounds, one of the most notorious lynchings in American history took place in front of a crowd of some 15,000.

On May 15, 1916, a seventeen-year-old Black farmhand named Jesse Washington stood trial for the murder of Lucy Fryer, a white farmer’s wife and a mother. Washington, who was illiterate and thought to suffer from an intellectual disability, had worked with his brother for the past few months on the Fryers’ cotton farm in Robinson, just south of Waco. He initially denied any involvement in the murder, but later, under questioning, is said to have confessed to the crime. He signed the transcribed confession with an X. Just one week after the murder, the evidence was hastily presented at trial, and a jury of twelve white men convened. After four minutes of deliberation, they issued a guilty verdict.

Chaos broke out in the courtroom. A mob of white men grabbed Washington, wrapped a chain around his neck, and dragged him a couple blocks toward the Brazos River, stabbing, beating, and stoning him along the way. On the grounds of City Hall, in full view of the Black part of town on the opposite bank of the river, members of the mob doused Washington in coal oil, mutilated him, then hung him from a tree and burned him to death. Later, a horseman dragged his body through the streets before young boys pried out Washington’s teeth to sell as souvenirs. As the horror unfolded, the thousands of spectators who filled the lawns of downtown Waco, including children who had been released early from school, ate picnic lunches and cheered. The events were documented in horrific detail in photos taken by Fred Gildersleeve, a commercial photographer who had set up his camera in a window at the mayor’s office.

The atrocity, which became known as the “Waco Horror,” was widely covered at the time. The nascent National Association for the Advancement of Colored People used it as a centerpiece of its anti-lynching campaign. Then it was largely forgotten for almost a century, at least outside of the Black community in Waco. For decades, the city’s civil rights leaders and organizations such as the Community Race Relations Coalition have been fighting for some kind of marker officially recognizing this event and others like it.

Finally, on February 12, before more than three hundred spectators, a row of news cameras, and several living relatives of Jesse Washington, the community dedicated a marker. As some of the state’s leading Republican politicians fight to suppress ugly aspects of Texas’s history by proposing bans on library books and diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, the marker’s advocates say it’s no small thing that this testimonial now stands for all to see, directly in front of City Hall.

Public-spectacle lynchings like Washington’s occurred throughout the country around the turn of the twentieth century. The Equal Justice Initiative, an Alabama-based nonprofit that provides legal representation for prisoners, estimates that between 1877 and 1950, more than 4,000 African Americans were killed in racial terror lynchings in the US, including 335 in Texas. During the same period, more than 1,000 white Americans were lynched, and extrajudicial killings of Mexicans and Mexican Americans raged throughout Texas.

Then, as now, images proved more powerful than words in catalyzing national uproar. Periodicals in Austin, Houston, and San Antonio denounced the horror, as did others throughout the country. The massive crowd, the horrific details, and Gildersleeve’s grotesque photos motivated the NAACP to send a young white woman, suffragist Elisabeth Freeman, to Waco to investigate. Using Freeman’s findings, W. E. B. Du Bois, writing in a July 1916 supplement to the NAACP’s magazine, the Crisis, said, “Any talk of the triumph of Christianity, or the spread of human culture, is idle twaddle so long as the Waco lynching is possible in the United States of America.”

Lynching violated Texas law, but none of the mob’s ringleaders were prosecuted. Many Waco residents who spoke to Freeman expressed regret at what had happened and at the fact that the city’s police chief, mayor, and other community leaders had stood idly by. “The feeling amongst the best people is one of shame for the whole happening,” Freeman wrote to her supervisor. “They realize it could have been stopped if they had had a leader—now they think they are right in trying to forget it & fancy the world will do so too.”

Of course, some never forgot the story. Yolanda Jones, whose great-grandmother was Jesse Washington’s niece, grew up in Waco in the seventies and eighties. The story of Washington’s horrific lynching had been passed down through the generations, and Jones said family members still feel the trauma of that terror today. “Being in the family that that tragedy took place with is like something you would only expect in a movie,” Jones said. “You wouldn’t actually expect for that to have been reality, but knowing that it is reality, my question is just ‘How?’ How could someone have so much hatred in their heart to do this to a human being?”

In 2006, the late Lester Gibson, then Waco’s only Black county commissioner, told NPR, “I had been hearing about [the lynching] all of my life.” Linda Lewis, who was born in Waco thirty years after Jesse Washington’s death and graduated as valedictorian of the segregated Black George Washington Carver High School, said her grandfather would sit on his front porch and talk with other old men. “One of the things they talked about was the hanging of Sank Majors on the bridge”—another of Waco’s gruesome lynchings—“and, of course, of Jesse Washington.” Fearing for Lewis’s safety, her parents told her she wasn’t allowed to cross the bridge into west Waco—white Waco—without an adult chaperone.

Still, the story remained relatively unknown throughout much of the city. I grew up in Waco in the nineties and early aughts and never heard about lynchings. The late Lawrence Johnson, Waco’s only Black city councilman for many years, also grew up in Waco but didn’t learn about Jesse Washington until he was in his mid-forties, around 1995, when he visited the National Civil Rights Museum, in Memphis, and saw a photograph of the lynching. “I felt the pain of that incident for my town,” Johnson told author Patricia Bernstein in 1999. In a piece written for Texas Monthly that year, Bernstein explained that Johnson was pushing for some kind of memorial of the lynching, but many in Waco were resistant to such a measure.

Bernstein published a book on the Jesse Washington lynching in 2006. That same year, William Carrigan, a Waco native and professor of history at Rowan University, in New Jersey, published The Making of a Lynching Culture, an academic exploration of the roots of such violence. Both books built on historical research from the first academic account of the Waco Horror, which James SoRelle, an emeritus professor of history at Baylor University and a Waco native, first published in 1983. The 2006 books caught the attention of many in the city, including Jo Welter and the Community Race Relations Coalition (CRRC), a grassroots organization that had formed in 2001 to promote racial and cultural awareness within Waco.

Welter, the chair of the organization, saw that her group was uniquely situated to help gain broad support for an official recognition of past wrongs. The CRRC came up with a resolution that year, on the ninetieth anniversary of the Waco Horror, that recognized and apologized for lynchings, particularly that of Jesse Washington. It encouraged both the city council and the county commissioners’ court to adopt the same resolution or to craft their own. The governing bodies wrote statements expressing regret, but the commissioners’ court, in particular, resisted the stronger language the CRRC had proposed. County commissioner Ray Meadows told NPR, “It’s a very ugly part of history, I will say that, and I regret that it happened. But as far as me coming out and [apologizing], I didn’t have anything to do with it.”

Efforts to meaningfully recognize Washington’s lynching resumed in earnest in 2015, as the hundredth anniversary approached. Malcolm Duncan Jr., who was Waco’s mayor from 2012 to 2016, grew up in Waco in the fifties and sixties and never heard the story growing up. He did not enter the mayor’s office with any intention to recognize and apologize for lynchings, but he lent an ear when citizens like Welter urged him to consider bold action. “I think there was a lot of dissatisfaction with what happened at the ninetieth [anniversary], and it kind of guided towards the hundredth,” Duncan said.

The year 2016 was a major turning point. The CRRC hosted a memorial at which Duncan, on behalf of the city, apologized unequivocally. “If you’re wrong, own up to what you didn’t do right,” he said. “That’s how you learn and earn respect.” Duncan also emphasized that “Waco is not that place today.” He pointed to the residents gathered in the standing room–only community center as an example of a diverse group working together for a common goal. “We have relationships built on trust, and we have partnerships that bind us in overcoming our obstacles,” he said.

Meanwhile, the CRRC and former city council member Toni Herbert had begun pursuing a state historical marker through the Texas Historical Commission’s Undertold Markers program. In the discussions leading up to the hundredth anniversary, the coalition met with Jesse Washington’s family, including Yolanda Jones’s mother, Shirley Bush, and Bush’s sisters Mary Pearson and Denise Mitchell. They asked how the family would like to commemorate the anniversary. “Their adamant response was: ‘We want to do the historical marker,’ ” Herbert says.

According to Welter and Herbert, by 2016 there was no fierce resistance to this effort, as there has been with historical markers in other parts of the state. That it took seven more years to finally erect the plaque had much more to do with bureaucratic delays, the sometimes slow-moving nature of volunteer work, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the shuttering of the Texas foundry that had produced the metal signs for the state. For about a year, Herbert poured herself into researching and writing a lengthy and detailed narrative of the lynching, which the historical commission used to create the text of the marker.

Welter and others insist that the racial terror of the past isn’t just an unseemly fact of history. Waco remains a city with vast inequality along racial lines. More than 35 percent of Black Wacoans are living in poverty, compared to about 21 percent of white residents. (The statewide poverty rate in Texas is roughly 14 percent.) As the city experiences economic growth and benefits from the positive publicity of Chip and Joanna Gaines’s media empire, it’s also seeing some of the gentrification that plagues historically Black communities throughout the country. “The truth for me as a Waco native is that my hometown remains not just racially segregated, but there remains a psychological and therefore economic segregation,” Lewis said. But both Lewis and Peaches Henry, the president of the Waco NAACP, applaud the city for efforts it has made to recognize and attempt to reconcile inequalities. “I’m very proud of Waco,” Henry said. “I do think that we are working in a very public way to do better in terms of not just race relations, but in terms of actual racial equity.”

After the performance of “Motherless Child” at the marker’s dedication ceremony, several speakers thanked those who had made the commemoration possible. Waco’s current mayor, Dillon Meek, was not able to attend the ceremony, but he had prepared an earnest video address. “We repent from the lynching and the darkness in our past with deep regret for the suffering it caused,” Meek said. He noted that the city council had formally adopted race equity as a priority.

All the speeches led up to that of Shirley Bush, Jesse Washington’s relative and Yolanda Jones’s mother. One could easily argue that this acknowledgement was too little, too late, but that’s not the attitude Bush and her sisters brought to the unveiling ceremony. Wearing a pink dress and floral leggings, Bush walked cautiously up to the microphone. She explained that she was nervous being onstage in front of such a large audience, but she proceeded to deliver a confident address. “He was lynched, but he became a legend today,” Bush said. She told the audience that the effort wasn’t over, but it was time to move on. “Let’s get out of this hole and get on the mountaintop and shout, ‘To God be the glory for this blessed day.’ ”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Texas History

- Waco

You must be logged in to post a comment Login