San Antonio Missions outfielder Joe Durham was leading the Texas League in hitting with a .391 batting average through fifty games in early June 1957. Here’s guessing no one then would have known what it meant that Durham’s OPS was 1.101. The minor-league club’s parent organization, the Baltimore Orioles, certainly knew it was time to get Durham into the majors and called him up on June 10.

Yet there were entire series played earlier that season when Durham was benched for lesser teammates. He sat neither because of a slump nor for any disciplinary reason. The 25-year-old standout knew beforehand he would sit out those series. When the Missions played road games against the Shreveport Sports, Durham didn’t play. He wasn’t allowed to play.

Joe Durham was Black, and in October 1956, Louisiana enacted a law banning interracial athletic competitions (as well as dancing). The Texas League’s first brush with the statute came in the 1957 season, ten years after Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color line on April 15, 1947—a date that MLB has celebrated as Jackie Robinson Day since 2004.

Shreveport was the only Louisiana franchise in the eight-team Texas League back then. Five teams were located in Texas—Austin, Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, and San Antonio—and two in Oklahoma City and Tulsa. Shreveport was also the league’s only independent team, without a major league affiliate feeding it players.

When Louisiana governor Earl Long signed the sports segregation bill, he said he was simply following the will of the people, estimating that 80 percent of the Louisianians he’d heard from favored it. State senator Willie Rainach, described in The Shreveport Times as a “legislative segregation leader,” said of the law: “This will help the Texas League get rid of its Negro players.”

Texas League president Dick Butler held the opposite view. “I can see no hope that Shreveport can remain in the league after this year,” he said. “Because the other Texas League clubs use Negroes and they will not agree not to use Negroes when playing in Shreveport.”

But they did.

In a 1990 interview in the Oklahoman, Butler referred to the Texas League of the 1950s as “the show.” It was. Major League Baseball wouldn’t arrive in Texas until 1962, when the Houston Colt .45s joined as an expansion team (it became the Astros three years later). Before then, Texans couldn’t even watch the big leagues on TV. The Texas League was the state’s highest level of professional baseball and probably the second-most popular sports organization after Southwest Conference football.

The Texas League integrated in 1952, when Dallas Eagles owner Dick Burnett signed pitcher Dave Hoskins, who led the league in wins that season with 22. Within three years, every team in the league except Shreveport had added Black players to its roster. Willie McCovey, the six-time All-Star and first-ballot Hall of Famer who played nineteen seasons for the San Francisco Giants, spent one season with the Eagles on his road to the majors. When Dallas visited Shreveport for a game in May 1957, the local morning newspaper described the heroics of the Eagles’ Mickey Sullivan, “who plays first base when regular Willie McCovey can’t play.” Any readers in northwest Louisiana surely recognized why McCovey wasn’t on the field.

Afro-Latino players from the Caribbean and Central America were also affected by the ban. One of the other Eagles who didn’t play in Shreveport that season was infielder Tony Taylor, a 21-year-old Cuban who went on to play nineteen major league seasons. Future big-leaguer Rubén Amaro, born in Mexico to a Cuban father, was in his second year playing shortstop for the Houston Buffaloes, an affiliate of the St. Louis Cardinals. When the Buffs opened the season in Shreveport, they moved Fred McAlister, an outfielder who would hit .214 that season, to shortstop.

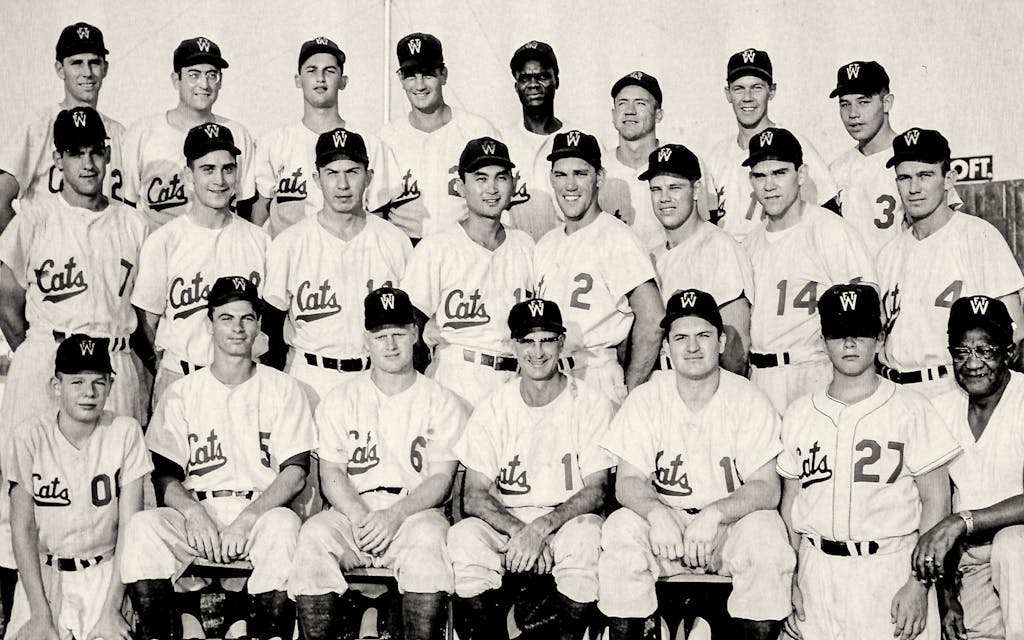

Lorenzo “Piper” Davis, then 39 years old, was an infielder for the Fort Worth Cats in ’57, winding down a career that began with the Birmingham Black Barons in the Negro Leagues in 1942. “All the towns in the Texas League were the same,” Davis told Bruce Adelson, author of the 1999 book Brushing Back Jim Crow. “Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antone—You were a n— anywhere you went. I’ve been called ‘Black boy,’ ‘rastus,’ ‘coon,’ ‘snowball,’ ‘alligator bait.’ I can’t tell you how many times I heard, ‘Stick one in that n—’s ear!’”

The Buffs’ Amaro told Adelson of being denied service at restaurants in Austin, Dallas, and Fort Worth: “After they said, ‘No service’ [in Dallas],” everybody on the team said, ‘We’re not going to eat,’ and they all got up.”

While African Americans weren’t the only players affected by the ban, they were definitely its primary target. The Louisiana legislature began considering the sports segregation law after the state’s premier athletic event, New Orleans’s Sugar Bowl, was first integrated, on New Year’s Day in 1956, by the University of Pittsburgh Panthers.

News of the Louisiana law was far from welcomed by the other Texas League team owners, who urged Shreveport owner Bonneau Peters to defy it. Peters, an oilman known as “Mr. Baseball” and “Mr. Pete,” had no such intention. Nico Van Thyn, a retired sportswriter for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram who grew up in Shreveport, pointed out a related passage about Peters from former Sports player Ed Mickelson’s 2007 memoir. According to Mickelson, Peters said his team would never have Black players.

Three of the Texas League teams—Dallas, Houston and the Austin Senators—approached Butler before the 1957 season with a compromise offer. If visiting teams were forced to bench their Black players for games played in Shreveport, the Sports must bench the same number of players of equivalent value. The proposal was given a nickname: “an eye for an eye.” Peters didn’t see eye to eye with that and flatly rejected it.

Butler did approve adding an extra roster spot for teams that would be forced to sit players—but only one. The Dallas Eagles went to spring training considering six Black players for roster spots, with manager Salty Parker expecting at least three—McCovey, Taylor, and right-fielder Bobby Prescott—to make the starting lineup.

According to C. Paul Rogers III, president of the Dallas–Fort Worth chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research and a professor at SMU’s Dedman School of Law, the Texas League team owners besides Peters believed Butler could find a way around the Louisiana law. But, Rogers added, Butler had no choice but to acquiesce unless one or more of the teams challenged the law in court. None did.

There was also speculation that the Texas League might swap the Sports for the Little Rock Travelers, a minor league team in Arkansas. The Travelers played in the eight-team Southern Association, which remained all-white under Jim Crow segregation. If the trade had come off, teams visiting Shreveport wouldn’t have faced the competitive disadvantage of sitting star performers, and Texas League teams would have been able to field their integrated rosters on the road in Arkansas. But Butler called the rumored exchange “difficult,” and it never occurred.

Texas League teams in 1957 played a schedule identical to that used then in the majors—154 games, 11 home and 11 away against each of seven opponents. The Louisiana ban would affect about 7 percent of the games played by each Shreveport opponent. Even though the league’s Texas and Oklahoma franchises remained integrated, it’s likely that the Louisiana law limited the number of Black players other teams could carry on their rosters. “The Missions have nothing against Negro players, but you can’t have more than one in your regular lineup,” wrote San Antonio Express sports editor Dick Peebles early that season. “Otherwise, the club will be weakened too much on visits to Shreveport.”

Whatever advantage the Sports may have gained from Louisiana’s sports segregation law, it wasn’t enough to keep the all-white team out of last place by the time the All-Star break rolled around in 1957. Shreveport, with a record of 39–64, trailed the first-place Eagles by 33 games. That’s when Peters informed the league’s other owners that he was selling the Sports, saying he had grown tired of seeing empty stands at games. A boycott organized by Black fans in Shreveport that season likely contributed to the poor attendance numbers, although Peters refused to admit it. “I don’t believe that Negro attendance in any Texas League city is enough to make the difference between success and failure,” he said.

Failure accurately described Shreveport’s season on and off the field. The Sports finished last at 59–95, with a cumulative attendance of 40,919 in the franchise’s 77 home games. The team attracted fewer overall fans that year than any other AA or AAA club in the country.

The Louisiana law turned out to be a one-season ordeal for the Texas League. Peters couldn’t find a local buyer to take over the Sports, and the team was moved to Victoria, Texas. Mark Presswood, a Texas League historian from Fort Worth, said that if Butler and the other team owners had wanted to preserve the franchise in Shreveport, they could have figured out a way to achieve that. They didn’t.

In November 1958, a federal court in New Orleans found the law unconstitutional after a Black boxer named Joseph Dorsey Jr. sued the state for preventing him from competing there. Louisiana appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld the lower court’s ruling in May 1959.

By then, the Texas League’s status as “the show” in the Lone Star State was near its finish. After the 1958 season, the league’s Dallas, Fort Worth, and Houston teams moved up to AAA. By 1962, Houston had a major league franchise.

Shreveport eventually returned to the Texas League in 1968, as an affiliate of the Atlanta Braves, and its roster included San Antonio native Clarence “Cito” Gaston. The Shreveport Braves were the city’s first integrated ball club, and Gaston would eventually go on to manage the Toronto Blue Jays to titles in 1992 and 1993, becoming the first Black manager of a World Series winner in MLB history.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login