In Crystal City lie the remains of an enormous swimming pool. The circular structure, which stretched for 250 feet across and was originally an irrigation tank, was filled in long ago. Now all that remains is a field of cracked concrete, overgrown with grass and weeds parched by the South Texas sun, in this small town about two hours southwest of San Antonio. In the 1940s, the swimming pool was an oasis for the more than three thousand people of Japanese, German, Italian, and Latin American descent who were locked up at the Crystal City internment camp—up until the drowning of two Japanese Peruvian girls in 1944 imbued the spot with tragedy. I’m here, not far from a statue of Popeye guarding city hall, for the unveiling of a monument to honor this land’s story. In a town that still proudly owns its proclamation as the “Spinach Capital of the World,” even though the cannery has been closed since 2019, history is not easily forgotten.

On an idyllic afternoon last October, about 150 of us sit on metal folding chairs atop the former pool. Rural set design—a warehouse and a silo—stains an otherwise pristine view of a big live oak. Community members and former internees have gathered here for an interfaith ceremony that will unveil the monument and mark 75 years since the camp closed. The event was organized by the Crystal City Pilgrimage Committee, one of many such groups of descendants who return to the sites of internment camps across the country. Internees and their relatives, dressed in black T-shirts with the logo of a watchtower, sit and stand shoulder to shoulder with some of the six thousand townspeople, all holding paper programs. Everyone is silent as Buddhist reverend Ron Kobata, in a black robe, steps forward and strikes a bronze bell: Ding. Ding. Ding.

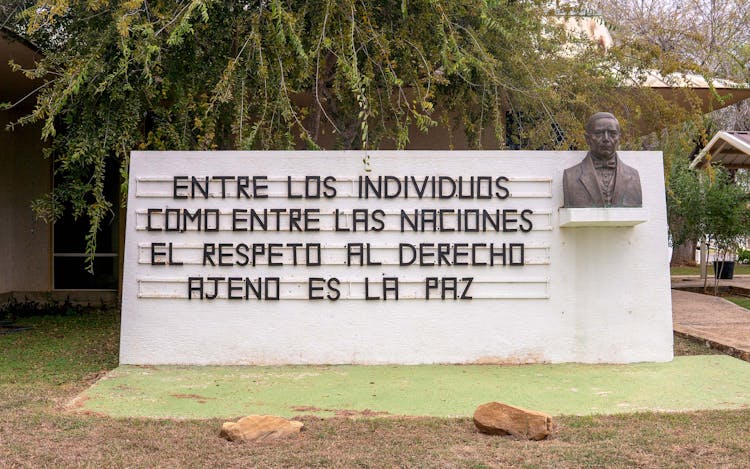

There is a strong and perhaps surprising sense of solidarity between the cristaleños, as the town’s Latino residents call themselves, and the former internees and their descendants. In a bitterly divided country that cannot agree on how to deal with Confederate monuments, lessons in textbooks, and literature in schools, the scene here is different. Both groups in Crystal City suffered systemic racial and ethnic discrimination and are now pushing for their long-overlooked civil rights history to be remembered. In 1969, more than two thousand students in Crystal City’s public schools walked out of class (some of them from the same buildings where internees had been educated twenty years earlier). They were protesting discrimination at school, where speaking Spanish was forbidden and Mexican American history wasn’t taught. That historic protest helped set the stage for a Chicano political revolution and the formation of La Raza Unida, a political party that changed the South Texas landscape forever.

Ding. Ding. Ding. Kobata reads the names of the 33 Japanese who died in the camp. Among them: the ten-year-old Japanese Peruvian girls, Aiko Oyakawa and Sachiko Tanabe, who drowned in the pool. Dozens of guests walk up and place marigolds on an altar. Then a former detainee named Hiroshi Shimizu comes forward. A slight man in his eighties, with a closely trimmed white beard and a radio voice, he carries a colorful garland of 33 tsuru, or paper cranes—a Japanese symbol of healing.

Kobata rings the bell again, at first slowly, and then faster, before chanting the Heart Sutra—a meditation on the impermanence of suffering and all human experience. As the words reverberate through the loudspeaker, ten or so former internees seated beside Shimizu behind the podium line up to place their flowers. At first the cristaleños hang back, waiting until all the Japanese internees and descendants have taken their turns. Then they, too, line up with bright orange marigolds in their arms. The bright blossoms remind me of two lines of a poem written by an internee in the camp: “Even in midwinter / flowers bloom in the yard.”

Kazumu Julio Cesar Naganuma was born in Callao, Peru, the child of Japanese immigrants who came to Peru in search of work and eventually opened a laundry business. He was not yet two years old in 1944, when FBI agents arrested his father, who was a community leader, at gunpoint. They gave his family three days to pack their belongings. Kaz, his parents, and his six siblings were put on a ship that sailed through the Panama Canal over a weeks-long journey, docking at New Orleans on March 21, 1944. The Naganumas and other detainees were then loaded onto a train and later a bus to Crystal City. Kaz and his family were among hundreds of victims of a coordinated effort between the State Department and Latin American countries such as Peru and Costa Rica codenamed Quiet Passage. The secret prisoner exchange program, which lasted from 1942 to 1945, involved arresting people of Japanese, German, and Italian descent who were living in Latin American countries; they were swapped for American prisoners of war in Axis nations, including businessmen, diplomats, soldiers, and missionaries, as former Texas Monthly staffer Jan Jarboe Russell explains in her book The Train to Crystal City. In all, the Crystal City family internment camp jailed first- and second-generation Japanese Americans, German American citizens, German nationals, Italian nationals, and residents of Peru, Bolivia, Honduras, Panama, and ten other countries, including a small group of Indonesian sailors.

Ten-foot-tall barbed-wire fences confined one hundred acres that previously served as living quarters for migrant farmworkers. Dotted along the perimeter were six guard towers. They looked over a small village complete with 103 tiny family homes, known as “Victory Huts,” German and Japanese schools, a German biergarten, warehouses, a clothing store, latrines, a Japanese sumo wrestling ring, basketball courts, playing fields for football and baseball teams, and a citrus grove. Children and adults locked up at Crystal City passed the time by forming Boy and Girl Scout troops, putting on sumo wrestling competitions, and staging plays. The Japanese internees even created their own newspaper, Jiji Kai (other papers at the camp included the English-language Crystal City Times, the Spanish Los Andes, and the German Das Lager) and gathered to write poems—some about the lives they missed back home, others about their days in the camp—in their tanka club, Tekisasu Shisha, or the Texas Poetry Society.

Hiroshi Shimizu was three years old when he was sent to Crystal City with his parents. He’d been born in another internment camp, the Central Utah Relocation Center, and together with his mother, Fusako; father, Iwao; and grandfather Iwajiro, was shuffled between five such facilities before ending up in South Texas. He was three and four years old during his time in Crystal City. I asked him if he knew that he was living in an internment camp. Shimizu was quiet for some time before replying. “I don’t think I had any concept of incarceration or freedom at that time.” Then an even longer pause. “But I realized also that we were confined, as opposed to incarcerated.” He and the other kids found ways to play and normalize their experience. What were intergovernmental prisoner exchanges and the suspension of civil liberties to a kid who had just “discovered the joy of sliding down poles”?

Maurice Yamasota, who lived at the camp for two years as a little kid, vividly remembers watching an officer who patrolled the exterior of the barbed-wire fence on horseback. Instead of wishing he could escape, Yamasota said, “I felt sorry for the mounted guard. They couldn’t come in because of the fence.” José Luis Balderas, who lived not far from the camp as a boy and later became the city manager of Crystal City, remembers bringing fruit to the internees, separated from them by barbed wire. “We used to have an orchard downtown, all the way for about seven, eight blocks, and nobody was allowed to pick the oranges,” said Balderas. “We used to come in when the police weren’t watching us, and we’d pick a few oranges. We’d go over to the camp, and the guard knew us. We had a little sack, five or six oranges, and the guard would turn around and look the other way. And we would roll the oranges, and they would throw back some stuff, candies.” Yet as Alberto Gonzales, a close friend of the pilgrimage committee and the former superintendent of Crystal City ISD, said, “There’s a saying in Spanish: Aunque que la jaula sea de oro, sigue haciendo jaula.” A golden cage is still a cage.

The Texas Poetry Society, and, more specifically, the act of writing, gave internees a rare opening to express their feelings. In the home of Dr. Motokazu Mori, a highly educated physician and prolific tanka poet in Honolulu, the thirty or so Japanese internees who made up the Texas Poetry Society met regularly to write together, and they completed an anthology of more than three hundred poems titled Nagareboshi (Shooting Star), which now resides in the Hawaiian & Pacific Collections at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Library. The poems in the book are tanka, a form of lyric poetry similar to haiku but slightly longer. For Texas Monthly, Eri Yasuhara, a retired professor of Japanese language and literature and dean emerita at California State University, San Bernardino, recently translated some of the poems into English for the first time. “Traditionally in Japanese culture, there weren’t that many avenues for expressing emotion, and tanka was one of them,” Yasuhara said. (Her grandfather was interned, at Tule Lake, in California, and almost never spoke of the experience.) “And so what are the emotions that are going to be expressed by people who are in a prison camp unjustly?” The answer: shame and the pain of day-to-day survival.

For the internees, the poetry was a means to pass time. “One of the hardships that we don’t often think about is enforced idleness. There’s not a lot to do,” Yasuhara said. “The plain, the vast space that expands where there’s nothing, comes up again and again in these poems.” One writer notes that “the loneliness of space / closes in on me.” Others find solace in the natural world; “Through dusk’s darkening sky, / Pointing southward, / A shooting star!” Stargazing is a recurring theme. “We’ve moved here / to Texas / where we see stars of such mysterious beauty.” Some lines reflect on the slow passage of time and on the experience of raising children. In one poem, a parent misses “a child / who answered the call” of the military draft. Another seems to express pride for “the children I taught / to become the bond / between Japan and America.” And one more mentions “the happiness of being a mother.”

Two months after the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the camp began final releases, and the group was “shocked into action,” quickly finishing the book while they were still together, explains Sojin Takei, executive secretary of the poetry club, in the afterword. “This collection is our ‘beloved child’ conceived in camp,” he wrote. “It is thus a humble product that just barely saw the light of day.” Eventually, three years after the bombs dropped and the poetry club finished its work, the camp closed, on February 27, 1948.

“I have a real strong memory of leaving the camp,” said Shimizu, who was four and a half at the time. “We got to the gate, I remember, and there was a truck waiting for us. And they loaded our luggage into the truck. I think my mother and two sisters sat in the front with the driver, and my father and I sat in the bed of the truck. On that day, as a departing gift, my parents had bought a little cap for me. I loved that cap. It was a real favorite of mine. But as the truck started moving away, the wind caught it and blew it off, and my father tried to yell out to the driver to stop. But he didn’t hear and just kept on going. And I could see the cap laying in the road.”

Shimizu’s father, Iwao Shimizu, was the spokesperson for Peruvian Japanese and U.S. citizenship renunciants at Crystal City. Like father, like son, Shimizu is now helping lead the pilgrimage committee, not just here but also as president of the one for the Tule Lake site, in northern California. There and at the sites of other former camps, pilgrimage efforts have sometimes sparked controversies and even lawsuits with locals. At Tule Lake, survivors and descendants are still arguing with the Federal Aviation Administration over the agency’s plans to restrict access to parts of the site, which is a working airfield. But not in Crystal City. Here, the committee and the cristaleños “broke tortillas,” as one participant put it, and shared solidarity.

In March 2019, roughly eighty people gathered in Dilley, 45 miles east of Crystal City, to protest the detention of migrants at the South Texas Family Residential Center. Among the activists, many of whom wore T-shirts that read “Stop Repeating History,” were Naganuma, Shimizu, and other internees and their descendants. Following that trip, three former internees, Naganuma, Shimizu, and Victor Uno, decided to file the paperwork to establish a 501(c)(3) nonprofit and officially form the Crystal City Pilgrimage Committee. There had been a pilgrimage to Crystal City in 2002, with a larger coalition of German internees, for the sixtieth anniversary of the camp’s opening, but this newly reenergized committee had bigger plans. It applied for (and received) a $150,000 grant from the Takahashi Family Foundation to help pay for the memorial at the swimming pool and for a study into the feasibility of someday creating a museum here. And the group gathered once more before the big pilgrimage this past October.

In 2022, Shimizu, wearing a Crystal City High School football shirt and a matching Javelinas hat, traveled with two others from the pilgrimage committee to attend the town’s annual Spinach Festival. Held each November, the community event includes live tejano music, a beauty pageant, a parade, a car show, food, and carnival rides. In a speech on the first night of festivities, Mayor Frank Moreno Jr. honored the pilgrimage committee, as he had in previous years. The public acknowledgement followed a roundtable meeting earlier that day between members of the pilgrimage committee and community leaders—Moreno, school board members, the superintendent, teachers, the city manager, and others. For the Japanese American pilgrims and Tejanos in the room, common ground was easy to find.

“We know exactly how you felt. We felt the same kind of racism that you all felt when we were growing up,” Ruben Salazar told the group. Salazar is a history teacher at Crystal City High School and a member of the pilgrimage committee. “I felt like a prisoner there too,” said Arturo “Turi” Gonzales, president of the Zavala County Historical Commission.

Salazar and Gonzales grew up in the 1960s, a period of dramatic political change in Crystal City. Mexican Americans, many of whom were migrant laborers, had made up more than 80 percent of the town’s population since the 1930s, but the white minority kept a tight hold on city government. A battleground formed in the schools, also dominated by white administrators. Mexican history, culture, and literature were not taught or included in textbooks.“You would get whipped for speaking Spanish,” said Gonzales. “Whites had an advantage over us on everything, including corporal punishment, where physically we were beaten with paddles for just about anything. . . . We finally said we’re going to put a stop to it.” Starting on December 9, 1969, about two thousand students in Crystal City, ranging from elementary schoolers to high schoolers, held a weeks-long walkout. About a month later, three hundred young activists met in Crystal City and formed La Raza Unida. Though the political party was sometimes described as radical, “I didn’t feel that it was a radical, militant party,” said Gonzales. “To me, it was just a tool that we needed to get into office. And that’s what we did.” With it, according to one of the cofounders, José Angel Guitérrez, “we created a Chicano middle class in Crystal City” and across South Texas, igniting a period of winning local elections and empowering Mexican Americans.

After the roundtable finished, we headed to the high school for a dedication service at the site of the camp. Just in front of Crystal City High School, next to slabs of concrete that were once the foundations for internees’ Victory Huts, the five-hundred-person high school student body gathered around a granite block monument erected in 1985. Members of the class government stood next to it and came forward, presenting Shimizu with a large wreath adorned with ribbons in green and yellow, the school colors.

One year later, sun-faded, it hung in the same spot—on an oak tree next to the granite monument. Less than half a mile away, after participants passed through a flower-covered arbor next to “Welcome Back!” signs at the entrance to the former swimming pool, the ceremony began.

Mayor Moreno spoke, as well as the Zavala County judge and the city manager. We honored the young Spinach Festival Queen and her court, who stood in front of the arbor in dresses and tiaras, handing everyone marigolds to be placed on the altar. Then the ding, ding, ding of the Buddhist service began, and Shimizu laid down the paper crane garland. The unpredictable rhythm of the chant continued as two columns of guests—a motley of green polos and black T-shirts, cowboy hats mixed in with San Francisco 49ers and University of Hawai‘i ball caps—shuffled closer to the table. Once the names were read and everyone sat down, Tommy Dyo, a nondenominational Christian minister with gray hair and a childlike smile, gave a sermon.

“I love my country, with all its bumps and bruises, flaws and mistakes. I can get angry at things. But I am also quick to forgive,” said Dyo, whose grandfather was interned in the camp. “The central theme of the Christian faith,” he went on, “is not good work. It’s not clean living. But it is forgiveness.”

After the oohs and aahs at the memorial’s unveiling, the events of the day ended with a tour around town to various sites from Crystal City’s history. The first stop was about two hundred yards from the entrance to the swimming pool, where a new street sign had been erected in memory of the Japanese Peruvian girls who drowned. The street is now called Calle Aiko y Sachiko.

All the while, making each stop with no fuss, no tantrum, and not even a wail the whole day was a two-year-old named Zoe, the youngest of the pilgrims. She was there with her mom, Jan Karadimas, and her grandmother Rosa Yomogida. Yomogida, an eighty-year-old Japanese Peruvian woman who later lived in Hawaii, was around Zoe’s age when she was interned at the camp. Three generations stood together on a site of spoken history and unspoken emotion. When I asked Yomogida what it meant for her to bring her family to this spot, she said, “I think I’d be happy as her,” gazing at her granddaughter as she played with her mom’s sunglasses. “Look how happy she is,” Yomogida said, “just being a child.”

- More About:

- Texas History

You must be logged in to post a comment Login