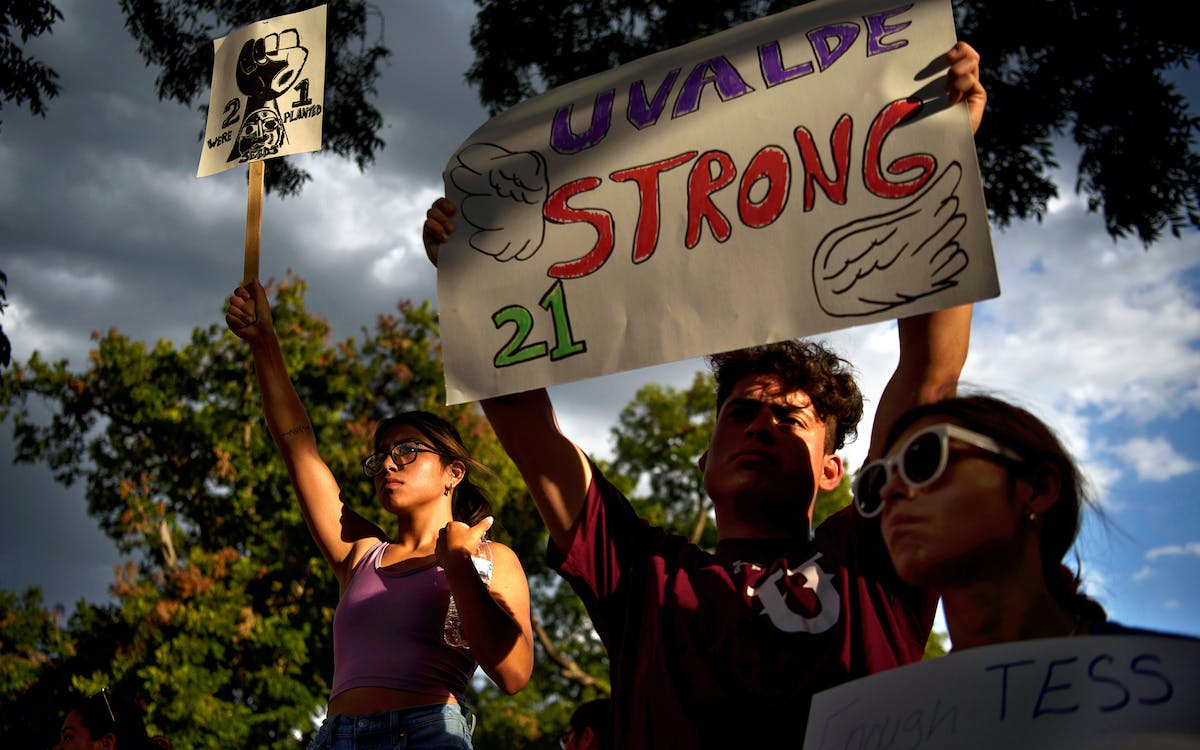

A carpet of color quivered beneath the sun, a baked garden of bouquets and stuffed animals, with crosses standing up intermittently from the fragrant heaps, each bearing a child’s name. A state trooper strode down a sidewalk, watching the crowd, standing between it and Robb Elementary School. It was July 10, at the start of the Unheard Voices March, a protest against weeks of silence and obfuscation by the Texas Department of Public Safety and local and state officials regarding the police response to the May 24 shooting at Robb Elementary, where nineteen fourth-graders and two teachers were murdered in the deadliest school shooting in Texas history. Women and men and children filled the street, packed in tight, holding signs, dabbing brows, quiet despite their anger—a flood behind a bulging dam. They surged into the square, where the makeshift memorial had stood for weeks, the grass trampled into oblivion by mourners and journalists and tourists. Members of the Brown Berets, a pro-Chicano social justice organization, mounted a platform with Jazmin Cazares, the teenage sister of nine-year-old Jackie Cazares, who was killed in her fourth-grade classroom at Robb. Jazmin led the rally. One at a time, the families spoke, calling for justice and transparency, for the firing of police officers, for political revolution in the city and state. As dusk descended, activists got in their cars and departed, perhaps never to return, while Uvaldeans made their way home, to sleep and rise again to the same intolerable stasis. James Baldwin wrote that once a people arise, they never go away. I wondered if that would be true here.

But by September, there were signs that Uvalde was reverting to equilibrium as the city’s institutions grew impatient with all the disruption. An August 14 Uvalde Leader-News editorial denounced the behavior of outside agitators—who attended city council meetings from as far as New York to denounce city leaders—and asserted that local officials would get it right in the end. Some church leaders criticized the protests; a deacon at a local Catholic church called activists “grievance hustlers” in the newspaper. Calls for “unity” multiplied across social media. Fewer and fewer people attended public meetings.

Just when it seemed as though those in power were ready to move on, Brett Cross, guardian of ten-year-old Uziyah Garcia, who was killed at Robb, began camping out in the parking lot of the school district’s central office along with his wife, Nikki, and a small group of victims’ relatives and supporters. Their demand: the suspension of the school district’s police officers who were working on May 24. For months, families had been demanding information about what happened that day—why nearly four hundred law enforcement officers waited more than an hour to act while a single shooter rampaged inside a classroom where children were dying. The school board had fired embattled district police chief Pete Arredondo in late August, but this had failed to silence calls for accountability. I visited the vigil on September 29, about two days after it began. Supporters came and went; the group seemed only a fraction of the July crowd. Even some of the most vocal advocates appeared to keep their distance. The administration played a waiting game, dealing with Brett passive-aggressively. He logged the hours on social media, making it clear that he wouldn’t leave until his demands were met, but his cause seemed forlorn.

Robb Elementary stands at the center of a Mexican American neighborhood in the southwest quarter of town. Before the shooting, the school had already had a dubious place in history as the flash point of a 1970 walkout, when hundreds of Uvalde school district students refused to attend class for weeks, protesting racial inequities in schools by marching and picketing while receiving instruction from activist tutors. The Mexican American community had been present in Uvalde from its earliest days, but over the years, deed restrictions and social pressure forced the barrios west and south. “Uvalde wants to portray that we stick together and we all care about each other, but it’s a facade,” Diana Olvedo-Karau, a native Uvaldean running a write-in campaign to replace Mariano Pargas as county commissioner, told me about a week into the Crosses’ sit-in. We spoke in front of El Progreso Memorial Library, which occupies the site of the old West Main School, whose plan it loosely follows. The foyer celebrates the school with depictions of students of all colors on a painted tile scene, a happy image belying the ugliness of de facto segregation. Olvedo-Karau grew up in the west side barrio, the child of migrant farmworkers. She was in elementary school during the walkout, but George Garza, whose ousting sparked the 1970 protest, was her teacher. “The division is [still] there, the unspoken, unconscious thought that some deserve and are better and others don’t: they live the lives they live because they don’t try hard enough,” she told me. “Those things are all there underneath the surface.”

The sit-in had begun to draw media attention within a couple of days; by October 5, eyes across the country were on it. That morning, Texas Democratic lawmakers and candidates met with victims’ families at the civic center. At the press conference that followed, families took turns making statements, but the Crosses were absent. Pastor Daniel Myers of Tabernaculo de Alabanza led a prayer, then pointedly asked the leaders if they would visit Brett in his vigil, which they did. Hours later came the bombshell revelation: Department of Public Safety officer Crimson Elizondo, who’d been caught on body-cam footage during the Robb shooting saying, “If my son had been in there, I would not have been outside,” had been hired by the school district a day after resigning from the DPS while under investigation. The board fired her on October 6, but the damage had been done. The next day, the district announced the suspension of the campus police department. “We did it!” Brett tweeted. “And we are going home!” After eleven days, the sit-in ended. But the protesting in Uvalde goes on.

In the months following the Robb shooting, Jesse Rizo, a tio of Jackie Cazares, has become a prominent figure in calls for accountability, frequently speaking out at school board meetings and elsewhere. He grew up on a farm in Batesville, where he worked in the fields daily. He has a college education and now owns a ranchito, something he feels he owes to his parents’ sacrifices but also to those who protested in the 1970s. I spoke to Rizo the weekend after the Crosses’ sit-in ended; we talked about La Raza Unida, a political party that had advocated for Mexican American civil rights in the seventies; we’d both recently attended its fiftieth reunion conference in San Antonio. “I see a lot of parallels to what we’re going through right now,” he told me. “They say history repeats itself. You hear stories, you meet people that were in the trenches, that stood up to injustice, and you wonder, how did they overcome all this?” Hearing those stories gave him hope, he said.

“I feel like a lot of people may be thinking that we’re trying to divide or we’re trying to tear down the school system or the establishment,” he said. “But what we’re trying to do is fight for the little guy; we’re trying to fight for the people that lost their lives.”

“I think it’s going to get worse before it gets better,” Kim Rubio, mother of Robb victim Lexi Rubio and a journalist at the Uvalde Leader-News, told me two days after a disproportionately white crowd of residents gathered outside a school board meeting in support of superintendent Hal Harrell, whose retirement had just been announced on October 10. “There’s definitely a divide now, and those that can forget want to forget—they want to move on already—and there’s the rest of us who will forever be stuck on May 24.”

Rubio told me about her long relationship with Harrell. She’d never called for his retirement, but she thought it was for the best. She was angry but unsurprised at the backlash. “I think we all saw it coming and we were waiting for it,” she said. She described angry comments she’d seen since the retirement announcement, aimed at those who had called for it: “You have torn apart our town.” “Why can’t you just move on?” “Why are we listening to this small group of people and not the majority?” But when it comes to calls for accountability, she said, “I don’t care if we have to tear this town down and start building from the ground up. If that’s what needs to happen, that’s what needs to happen.”

For Rubio, current events also echo the past. She pointed to the way nearby Knippa ISD, which screens transfer students and makes them leave if problems arise, and Uvalde Consolidated ISD’s dual-language academy, which is similarly selective and has a heavy workload that working parents often find hard to deal with, seem to embody the very injustices the 1970 walkout protested against. The irony is that bilingual education was a demand of the walkout. Has it been turned into another enclave?

I recently came across an April 15, 1970, letter to the editor by Al Dishman, Uvalde school district board president, written in response to the ongoing walkout:

It comes to my attention that there is a small militant group of dissidents among our adults who have no regard for the harmony which is the strength of our community. Having tried and failed to divide the adult population and thus destroy our fine community spirit, they have turned to the subversion of our youth (a practice, I might add, that is used by known Communists all over the world) in hopes of using them to achieve their aims of disruption of the harmony which we now enjoy.

Through the use of half truths, distorted facts, out and out falsehoods, and an organization called MAYO (Mexican American Youth Organization) they have dressed those whom they have persuaded to join (a relative few, I might add) in a serape-type costume, given them a name—Chicanos, armed them with such poisonous and hate provoking slogans as “Chicano Power,” “Down with the Gringos,” “La Raza,” etc. (Sort of reminds one of the pre-World War II days and the Nazi Youth movement in this country, doesn’t it?) and set them about the job that they themselves could not accomplish through the adult community.

The letter concludes with an appeal to the students: “Think about it . . . wouldn’t You rather be a winner?” Most were not, in a material sense: the school flunked them. Some were drafted in consequence and sent to Vietnam. But they changed Uvalde.

Soon after reading this, I had lunch with one of Dishman’s “dissidents,” Uvalde native Abelardo “Lalo” Castillo, who has also worked for accountability in the aftermath of the Robb shooting. “The only difference between then and now is the color: among the elected leaders, there’s brown faces and there’s white faces, and back then it used to be all white,” he told me. “But the system is the same.”

MAYO was started by a group of students at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio in 1967. Castillo joined soon after, and in 1970 he helped organize the Uvalde walkout. José Ángel Gutiérrez was one of MAYO’s founding members, and he later helped establish La Raza Unida, winning political power in Crystal City—Uvalde’s neighbor to the south—and throughout South Texas. As a party, La Raza had a short life that ended when its charismatic gubernatorial candidate, Ramsey Muñiz, who ran and lost against native Uvaldean Dolph Briscoe, went to federal prison after a 1976 arrest on drug trafficking charges. But La Raza as a movement—and Muñiz as a leader—had a lasting effect on the political landscape and the lives of Mexican Americans. (Muñiz died on October 2, 2022, at 79.)

Around Uvalde, attitudes toward La Raza are mixed. A February 24, 2016, editorial in the Uvalde Leader-News, written in response to FBI arrests of Crystal City leaders on bribery charges involving city contracts, laid the corruption at the feet of La Raza for having “thrown out the baby with the bath water” in the process of “fomenting the overthrow of everything ‘Anglo.’ ” But Castillo—who was trained by famed Chicago community organizer Saul Alinsky and went on from MAYO and La Raza to help organize communities around the country and run several successful businesses—has credited José Ángel Gutiérrez more than anyone else for helping him learn how to organize. “If it had not been for the Raza Unida party and the mobilization of people, the masses,” he told me, “we would be in worse shape today than what we are.”

I met Gutiérrez over the phone in June. He called me at my office after I wrote my last Texas Monthly piece, “My Uvalde,” which explored the historical racial divides in the small Texas town that was suddenly the center of the world’s attention. “I am José Ángel Gutiérrez,” he barked. “Do you know who I am?”

“Excuse me?” I said, not having processed this. I’m autistic, and I tend to avoid talking on the phone. Rapid-fire, Gutiérrez rattled off his accomplishments. I’d known about him for a long time, though. He and my father were at St. Mary’s at the same time, but instead of going to Cotulla to organize and tutor protesting students, my dad volunteered for Vietnam. People had told me that Gutiérrez is abrasive and passionate. Both qualities were evident in our conversation. “We need to get these gringos out of office!” he said. I’ve been blunt about the role of race in Uvalde, but I wasn’t certain that I agreed with this approach. He later made some bold proposals for how we could help through community organizing and education. They never came to fruition, partly through lack of funding and partly, perhaps, through my own ineptitude and isolation. I can write, but my social abilities are limited.

At the Raza Unida reunion, I heard nostalgia for a movement that had burned bright but too short. I heard bold political strategies, such as dividing Texas into five states, that (to me) verged on fantasy. I heard some bitterness, some resentment. I heard criticism of today’s youth for their smartphones and indifference. But most of all, I heard the passion that had been ignited at the height of the civil rights movement and fueled by the deep disparities in South Texas towns, and a commitment to social progress whose effects are still felt today.

As for getting gringos out of office, the people you see on the news are not necessarily the most important people in Uvalde. I’m not saying anything José Ángel Gutiérrez doesn’t know. Somehow, the most “expendable” officials, like Pete Arredondo, tend to be Hispanic. Elected officials like Mayor Don McLaughlin are a little less expendable. But much of the real power is in the hands of people you’ve never heard of. They’d prefer to keep it that way.

As of today, the personnel page of the First State Bank of Uvalde shows only a board table surrounded by empty chairs. The internet archive indicates that it’s been that way since at least May 27. But the prior capture, from January 28, listed all of the directors and officers, including its chairman, Chip Briscoe, son of the former governor, one of the richest men in the county, whose family in September announced its donation of $1.5 million toward the construction of a dog pound; president and CEO, Chad Stary, captured on camera sitting front and center at the May 25 prayer vigil and later embracing Senator Ted Cruz while they prayed together; and Randy Klein, owner of Oasis Outback, where the killer acquired his guns. The aloof invisibility of these figures brings to mind a castle with its drawbridges lifted.

With a small, fragmented protest movement opposed by the inertia and growing hostility of an entrenched social order, how will change be effected? I keep returning to something Jesse Rizo said: “You don’t need hundreds and hundreds of people behind you. All it takes is one person that stands up for what’s right against the bullying. And that one person says, ‘Enough is enough.’ It’s really all you need. You’ve got the spirit of twenty-one people that are with you. That goes a lot further than having the whole town.”

- More About:

- Uvalde

You must be logged in to post a comment Login