Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google. Read the transcript below.

So we sat down and he says, “I need to let you know that your great-grandfather was massacred by the Texas Rangers.” And we said, “Uncle John, the Texas Rangers don’t go around killing people. They’re supposed to be helping people.” He says, “No, not our family.”

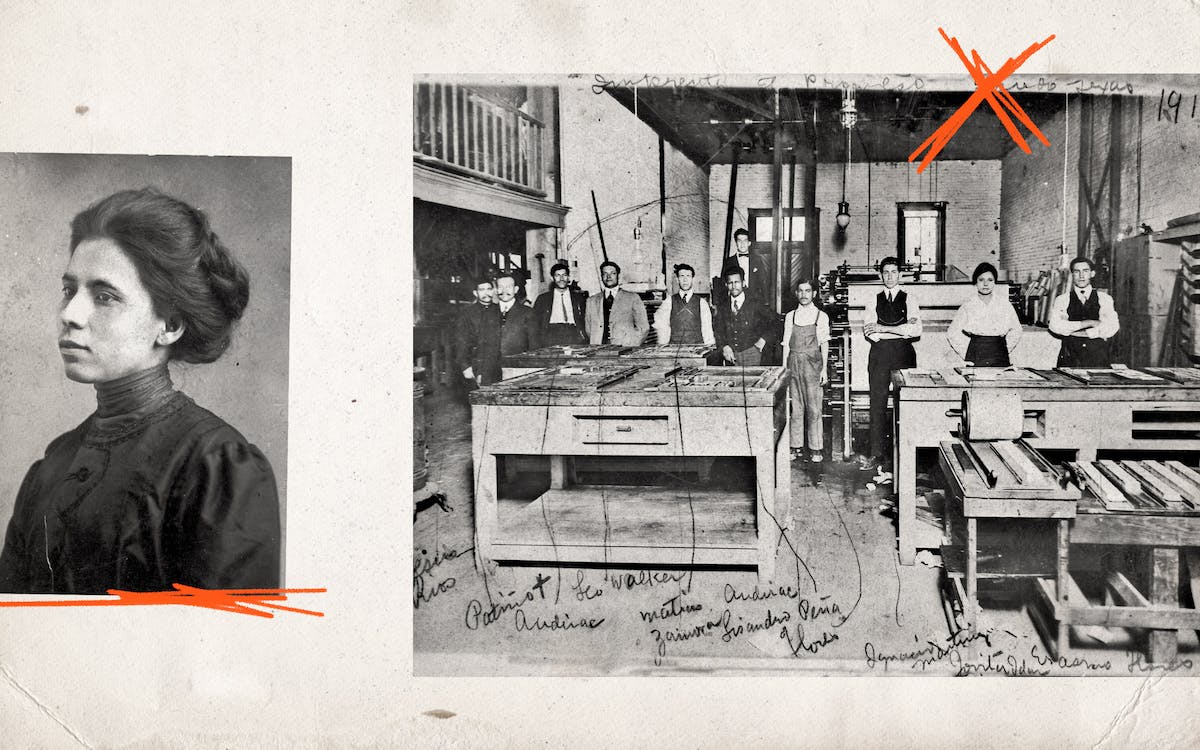

Arlinda Valencia

With the dawn of the twentieth century came the end of the Old West, and Texans began to wonder whether the Texas Rangers were still necessary. But after the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution, as fighters crossed into Texas to raid ranches, Texas hired hundreds more Rangers to defend the state—many with hardly any qualifications. The atmosphere of suspicion and fear between Anglo and Mexican Texans gave rise to an era of state-sanctioned violence by Rangers, vigilantes, and other officials. It reached its peak at a massacre in the West Texas town of Porvenir.

You can read more about the stories in this episode in Revolution in Texas, by Benjamin Johnson, and Redeeming La Raza, by Gabriela Gonzalez.

White Hats is produced and edited by Patrick Michels and produced and engineered by Brian Standefer, who also wrote the music. Additional production is by Isabella Van Trease and Claire McInerny. Additional editing is by Rafe Bartholomew. Our reporting team includes Mike Hall, Cat Cardenas, and Christian Wallace. Will Bostwick is our fact-checker. Artwork is by Emily Kimbro and Victoria Millner.

This episode features additional field recording by Zoe Kurland.

Archival tape in this episode is from the University of Texas at San Antonio Institute of Texan Cultures Oral History Collection. Special thanks to Arlinda Valencia, who provided tape of her conversation with her great-uncle, Juan Flores.

Transcript

By the end of the 1800s, Texas looked nothing like the rugged country Jack Hays and the early Rangers had first seen. The last Comanche holdouts had been forced onto a reservation in Oklahoma. Railroads crept across the state, turning frontier towns into bustling metropolises. The great cattle herds out on the range were fenced into feedlots; the first cars arrived in 1899. It was the end of the Wild West.

And, in a lot of ways, the Texas Rangers had come to look like relics of that past. By 1900, professional law enforcement had sprung up, even in small towns. It was getting hard to see why Texans still needed Rangers—and the state was getting tired of paying their salaries. In 1901, the Legislature downsized the force to fewer than one hundred men. The glamour of the job had faded.

Then, one day in 1909, in El Paso, things began to change.

[street noise]

Max Grossman: Cross yet? Here we go. So this was the river in, uh—oh wait, no, we can’t cross. Sorry.

I’m in downtown El Paso, standing where the Rio Grande used to run. Today, it’s all pavement—and you’ve got to look both ways before crossing.

Max Grossman: I saw the red light there.

Jack Herrera: [laughs]

Max Grossman: I wasn’t thinking.

I’m here with Max Grossman, a professor at the University of Texas at El Paso. He’s an expert in the city’s historic architecture, and, as we walked, he consulted a map on his phone that showed what the city would have looked like around 1909.

Max Grossman: Well, this area that we’re standing in is part of the original historic core of El Paso. It would have been a mixture of adobe and brick buildings, a mixture of buildings from, really, the Victorian era—from the time of the so-called Old West. Brothels, saloons, hotels, and so on from that period.

But El Paso was transforming quickly.

Max Grossman: The first reinforced-concrete skyscraper went up in 1909, and there were another half a dozen of them under construction by the end of the year. The streetcars, of course, were everywhere and extended in all directions. It really felt modern, busy, crowded, multicultural, optimistic, forward-looking.

In the same year that those first skyscrapers went up, U.S. president William Taft planned a historic meeting with the Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz. It would be the first-ever in-person meeting between a Mexican president and his American counterpart. It would be a way to bury the hatchet on the Mexican-American War and support growing U.S. business investment in Mexico. And they agreed to meet here, right on the border, in the sister cities of Juárez and El Paso.

For Díaz, the Mexican president, it was a risky trip. He had ruled for decades with an iron fist, but his grip was slipping—and many of his strongest critics lived in Juárez. Díaz decided that the hostility presented an opportunity: if the trip went well, the positive press could help him win over his opponents in northern Mexico.

Max Grossman: Because Mexico was becoming unstable quickly. The conditions for an armed revolt were in place, and there were already a lot of rumblings across Chihuahua state.

Tourists flooded into El Paso to watch. The streets and buildings were decorated with colors of both countries. But behind the flags and flowers, there was tension. Both Díaz and Taft brought thousands of troops with them. The friendly summit looked a lot like a war zone.

One member of Taft’s entourage was an old friend from Yale, the globe-trotting mining engineer John Hays Hammond—who was the nephew of Jack Coffee Hays, the legendary Ranger captain. Hays Hammond was worried that an assassination attempt on either president could imperil the new friendship between the two countries. For additional security, he hired a famous adventurer named Frederick Russell Burnham. Burnham led a security team with hundreds of men, including Texas Rangers.

As the presidents paraded through the city, the security team cleared a space around them and probed the crowd for threats. Burnham’s partner for that day was a young Texas Ranger named C. R. Moore. Taft and Díaz had almost reached their meeting place when Burnham looked into the crowd of reporters. He saw one man writing in his notebook who seemed suspicious.

In his autobiography, John Hays Hammond described what happened next: Burnham, he says, quote, “gave the secret signal to [Moore], and they closed in. [Moore] slipped his arm through the arm of the suspect, [and] at the same moment Burnham grasped his wrist. Quickly flipping over the busy scribbler’s hand, Burnham discovered that the pencil sticking out between the first and second fingers was actually the muzzle of a pistol especially designed to be hidden in the palm of the hand.”

Hays Hammond said: “Although the man with the gun declared he was a newspaper reporter, he was obliged to finish his story in jail.”

John Hays Hammond wrote that, quote, “Trouble was already brewing below the Mexican border. . . . If Díaz had been killed on American soil, all of Mexico would have been inflamed.”

The next year, though, Mexicans rose up against Díaz anyway. It became one of the most important, and chaotic, revolutions of the twentieth century. And it transformed the Texas borderlands.

Terrified at the prospect of Mexican insurgents raiding Texas towns, Texans did what they’d done many times before: they raised new Ranger companies.

The Mexican Revolution gave the Texas Rangers a new calling. But it also became the darkest chapter in Ranger history.

From Texas Monthly, this is White Hats: a story of the legendary Texas Rangers and a struggle for the soul of Texas. I’m your host, Jack Herrera.

This is episode three: “La Hora de Sangre.”

Across the borderlands, the chaos of the war in Mexico began to spill into Texas. Hundreds of thousands of refugees fled into the state. And revolutionary fighters passed back and forth across the border. Where Rangers had once protected Anglo settlers from Comanche raids, now they patrolled the border looking out for Mexican raids.

The atmosphere of fear and suspicion meant that anyone who looked Mexican could be accused of being an attacker, a revolutionary crossing the border to raid for supplies. The word Anglo Texans used for this sort of person was “bandit.”

Benjamin Johnson: But that’s such a prejudicial term that that implies that they’re guilty of crime and that they’re inherently law-breaking people, right?

That’s Benjamin Johnson. He’s a historian at Loyola University in Chicago, and he studies how the Mexican Revolution affected the Texas borderlands.

Ben told me that Texans weren’t just scared about armed revolutionaries crossing the border: they were worried about revolutionary ideas crossing the border.

Benjamin Johnson: There start to be land redistributions in Mexico, including basically right across the river from Brownsville, where formerly landless peasants are assembled in a kind of military-style ceremony and awarded certificates of a former hacienda. So a lot of people in South Texas start to think, “Wow, maybe we need something like a Mexican revolution, or at least a land redistribution.”

Anglos worried that Mexican Americans might even begin their own insurgency in the U.S.

Benjamin Johnson: And so in January of 1915, a guy named Basilio Ramos is arrested. And he has this incendiary manifesto called the Plan of San Diego that calls on a liberating army of all races to rise up and kick Americans out of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, and Colorado. In other words, to undo the U.S.-Mexican War, right? To undo 1848. And, you know, no one quite takes it seriously at first. But then, that summer, there starts to be a series of raids on irrigation works and prominent ranches and railroad infrastructure in South Texas, by what looks like a kind of guerilla army.

These rebels, called sedicionistas, were killing innocent people, even some people of Mexican descent. Panic spread through Texas. To respond, the Texas Legislature undid the law that limited the size of the Rangers, and instead raised new Ranger companies. Over four hundred “special Rangers” were commissioned, without any training requirements. It seemed like any man with a gun could get a Ranger commission. Eventually, the Ranger force was the largest it had ever been.

This is how the last great Ranger War began—against rebels on the border. In the Rangers’ history, it’s called the Bandit Wars. But Tejanos have another name for it: La Hora de Sangre, the hour of blood.

Benjamin Johnson: And particularly after the Plan of San Diego is unveiled, they round people up, drive people off their ranches. They torture people, kill people, who either they took into custody or who were turned over to them by other law enforcement officers.

Rangers who had captured prisoners would release them, and as they ran away, the Rangers would shoot them. They’d then record their deaths as suspects who tried to flee. In South Texas, townspeople would warn each other about “la ley de fuga”: “the law of escape.” It even alarmed local police.

Benjamin Johnson: Both a local Anglo sheriff, W. T. Vann, objects, and at one point draws his gun to prevent prisoners from being taken by the Rangers, and Frederick Funston, the general who was in charge of U.S. Army units dispatched to the border, threatens to put the border region under martial law to constrain the Rangers and vigilantes.

This is La Matanza, when hundreds of Mexicans were murdered along the border. Trinidad Gonzales talked about it in episode one. Benjamin says it’s important to understand that it wasn’t just Rangers doing the killing. Vigilantes and local cops killed more people than the Rangers did.

Benjamin Johnson: You know, I think what’s more complicated is, you know, when a governor says “These people are really dangerous,” and newspaper editors and prominent politicians say, you know, “We need to clear Mexicans out of here. We need to put them in concentration camps until this thing is taken care of,” and then private citizens go out and kill people—that’s not state-sanctioned as unambiguously as the Rangers, but it’s also not done in opposition to state authorities. And, you know, that stuff is not prosecuted either, right? People aren’t held accountable.

My Tejano family has roots in Texas that go back centuries. But this was a history I never knew: that hundreds of Mexicans were lynched in Texas.

Anglo newspapers described many of these dead Mexicans as bandits. But there were some who had the bravery to call the killings what they actually were.

Isabella Van Trease: So the headline here says, “Barbarismos.”

Jack Herrera: Like “barbarism,” or barbaric acts.

Isabella Van Trease: Yeah. The article’s about the lynching of a young Mexican American man named Antonio Rodríguez. The sub-header here says, “A Mexican was burned to death in Rocksprings by a horde of angry savages who do not respect either the law or human rights.” Then it goes on to call for unity among Mexican people, on both sides of the border.

This is Isabella Van Trease. She’s part of our production team on the show. And she’s been digging into the story of a family of journalists and activists in Laredo. Jovita Idár and her brothers and sisters and parents. In the 1910s, the Idár family ran what might’ve been the most fearless printing press in Texas. They exposed oppression and violence against Mexican people and called for change. They recorded life as it was for Mexicans in the borderlands.

Laredo is where my family roots go back, and it’s one the cradles of Mexican American identity. As a war lay waste to Mexico, and Rangers and lynch mobs attacked Mexican Texans, the Idárs called for solidarity.

Aquilino Idár: Out in the yard, my father used to sit right there, and all of us used to form a circle around him.

This is Aquilino Idár—who went by “Ike”—speaking to an interviewer in 1984. He’s talking about his father, Nicasio Idár, who ran the family printing press.

Aquilino Idár: And he would talk to us about Mexicans, about Mexican Americans, how to fight for the Mexican people, what to do for the Mexican people. How to think. “Don’t let anybody tell you how to think, because you are a freethinker. You are standing on the face of the earth on your own two feet.”

Ever since Trini Gonzales told me that the Rangers killed his great-grandfather, I’ve been trying to understand how men tasked with protecting Texans could commit such awful acts. And in the article Isabella showed me, I found an answer. Nicasio Idár understood what was happening.

Isabella Van Trease: So, this is another lynching, of Antonio Gomez, who is actually a fourteen-year-old boy. The headline here reads, “Cowardly, Infamous and Inhumane Lynching of a Young Mexican Man in Thorndale.”

Jack Herrera: You know, I’m realizing that this is the first time I’ve seen the word “lynching” in Spanish. “Linchamiento.” And so at this point in 1911, the Idárs are not mincing words.

Isabella Van Trease: Yeah.

Jack Herrera: And there’s this other line: Nicasio describes this animosity towards Mexicans as “la serpiente,” like a serpent that has poisoned Texans. So he’s saying that this hysteria, and this fear towards Mexicans—Nicasio understands that it goes beyond the Rangers. That it’s turning the Texans around him violent and aggressive. And it’s destructive to what he describes as the Texan organism—like, it’s destructive to the Texan spirit, the American spirit.

The Idárs’ work speaking up for Mexicans earned them enemies—including the Rangers. But they didn’t back down. It all led to one of the more inspiring moments in La Hora de Sangre: the moment when one Idár literally stood up to authorities trying to shut down the free press.

Jack Herrera: So you have another article here. The headline is “Debemos Trabajar.” So, “We Should Work.” And it talks about the modern woman.

Isabella Van Trease: It’s written by Jovita Idár, who is the daughter of Nicasio Idár. And in my research, I’ve discovered she really was a force of nature—an early Mexican American feminist. Her writing goes on to manifest in things like this, where she’s calling for gender equality.

Jovita wrote for La Crónica under pseudonyms: Ave Negra—Black Bird—or Astrea, the Greek goddess of justice. But today, she’s probably the best-known member of the family—in my mind, she’s one of the bravest American journalists of the twentieth century, along with Ida B. Wells and others who reported on segregation and lynchings.

Isabella Van Trease: In her life, Jovita called for women’s education and liberation—she was fearless. And her fearlessness was really captured in this one story.

At the time, Spanish-language newspapers were frequent targets of harassment from law enforcement. According to Jovita’s brother Aquilino, Jovita was working for another paper in town, called El Progreso. And, as he remembers it, El Progreso ran an editorial criticizing President Woodrow Wilson.

Aquilino Idar: It wasn’t a dirty editorial. It was just criticizing Wilson for his action of sending troops to Mexico. Says, “You didn’t have to do that, Mr. President.” He says, “That’s against justice, against law.” And the Rangers in Laredo didn’t like it. So they went to El Progreso, and they were going to destroy everything.

There’s some debate today about how and when this happened—and, importantly, whether it was Rangers or federal marshals who showed up. But this account from Aquilino is the one that’s taken hold:

Aquilino Idar: But it so happened that my sister was standing at the door. And she stood at the door and says, “Where are you going?” Says, “We want to go inside. Would you please step aside?” And my sister says, “No. You have to come through this door, and I’m standing here, and you cannot come in here because it’s against the law. If a woman stands at the door, you can’t go in.”

For me, and I think a lot of other Mexican American journalists, this is an incredible moment. Jovita Idár stands her ground, stares the men in the face, does not flinch in front of their guns, and tells them that they will not pass.

But it’s not how Aquilino’s story ends.

Aquilino Idar: Well, they did . . . next morning, real early, about five o’clock in the morning . . .

This was the next day.

Aquilino Idar: My sister wasn’t there, so they broke the door. And they broke the linotype machine, kicked the keyboard, kicked the press, all the type. They threw it on the floor like that. The loose type that was on the stands, they pulled all these boxes and emptied it on the floor. They broke the press with the sledgehammers and everything.

If authorities and vigilantes weren’t afraid to attack newspaper offices in a crowded city like Laredo, Mexicans living in remote villages were even more vulnerable—villages like the one on the bank on the Rio Grande, far west in the mountains of the Big Bend: a town called Porvenir.

Arlinda Valencia: Yeah. Well, I grew up with the Lone Ranger and Tonto. And every Saturday morning, I think we’d get up to watch the series—I mean, he was supposed to be the best lawman. And so I grew up thinking the Texas Rangers were just heroes.

This is Arlinda Valencia. I met her at her home, just outside of El Paso. We sat in her living room. Photos of her two children were up on the walls. Every inch of the place was impeccable and organized.

Jack Herrera: From what I can guess, there’s a moment that your impression of them began to evolve, or adapt. And can you tell me about how that happened?

Arlinda Valencia: Well, it wasn’t over time. It was just—boom.

Arlinda is an educator, and now a union leader for teachers.

Arlinda Valencia: It was at my dad’s funeral.

Jack Herrera: What year was that?

Arlinda Valencia: Nineteen ninety-six. And my uncle, John, my dad’s brother, he’s the one who came up to us, and he said, “You know, I have to tell you guys a story.” So we sat down, and we were listening to him, and he says, “I just need to let you know that your great-grandfather was massacred by the Texas Rangers.” And that’s when all of us just looked at each other and said, “Yeah, right.” And he goes, “No, no, it’s true.” And we said, “Uncle John, the Texas Rangers don’t go around killing people. They’re supposed to be helping people.” He says, “No, not our family. And they lived in fear all these years and they never said anything, but I think it’s time that you guys knew.”

Arlinda says she didn’t really believe him. How could something like that have happened, and she’d never heard about it?

Arlinda Valencia: And so, we just said, “Let’s start looking for evidence. If it happened, there’s got to be something out there that’s going to prove it.”

One day, she was reading an article on a Texas history site. It told a story about the village of Porvenir.

Arlinda Valencia: And I started reading about it, and I was shocked, because it said that these people from Porvenir had attacked the Texas Rangers. And that they had been defending themselves. And that’s why they ended up killing them all. But as I kept reading, they named all the men that had been murdered. And my great-grandfather’s name was there.

But not only did I see his name. At the very last paragraph, it named a wife that had said that if she were to see the murderers again, she would recognize them. And it was my great-grandmother. And so, you know, I was thinking, “Okay, but it says they were bandits.” So, that’s not what I had heard, that my great-grandfather was a bandit.

Jack Herrera: Had you heard stories about him, growing up?

Arlinda Valencia: No. No. My dad died and never knew the real story.

Jack Herrera: Really?

Arlinda Valencia: Yes, he didn’t know about it.

At her dad’s funeral, her uncle said he’d heard the story from her great-uncle, Juan Flores. They decided they needed to hear it directly from him.

Arlinda Valencia: So we traveled over there from Monahans to Odessa. That’s where he lived.

[greetings, sound of farm animals]

Arlinda and her sister recorded the conversation.

Arlinda Valencia: I’ll tell you this. When he lived in Porvenir, all his job was to take care of the goats. Every morning, he’d get up, go take care of the goats. And then after school, he’d come back and he’d take care of the goats.

Jack Herrera: How old was he?

Arlinda Valencia: He was in his nineties.

Jack Herrera: Wow.

Arlinda Valencia: Yeah. We were very lucky to have gotten to talk to him. My sister and I said, “Hey, we know the story. We want to hear it from you.”

[sounds of roosters and goats]

Arlinda’s sister: Eso que dice aquí. Tío, dice que cuando pasó esto, ¿Narciso tenía quince, dice que usted tenía once?

Juan Flores: ¿Cuándo pasaron qué?

Arlinda’s sister: Cuando mataron al abuelito . . . Longino Flores.

Arlinda Valencia, in interview: So anyway, we all sat outside. He was in his porch, outside, surrounded by goats. I thought that was just . . . I don’t know. It just gave me a good feeling that he still had Porvenir in his heart.

[Juan Flores speaking Spanish]

In Spanish, “porvenir” means “future.” Deep in a hostile desert in the mountains of the Big Bend, a group of about forty families settled on the northern bank of the Rio Grande. For generations, the river had flooded over the fields along the banks, and now the soil was rich and ready for farming. In the mornings, Juan Flores and the other children would attend a school run by a man named Harry Warren. It was a small miracle, the life they built there. Today, the river often runs dry.

Arlinda Valencia: It’s all just dead, desert. But when they lived there, they had corn; they had all types of vegetables. And people would come in—the soldiers’ camp would come in and buy the vegetables from them. And I believe that there was a little jealousy there, [toward] the farmers. The ranchers did not like the fact that they were doing well. They wanted them gone.

[rooster crows]

Arlinda Valencia: Pues, dicen que todo lo que pasó era por el Brite Ranch?

Juan Flores: Huh?

Arlinda Valencia: El Brite Ranch?

On Christmas Day, 1917, a group of Mexicans had raided a prominent ranch—the Brite Ranch—to the east of Porvenir, killing three men, including the local postman.

Arlinda Valencia: Dice el libro que robaron—los villistas robaron a un ranchero, era un gringo que se llama Brite.

JuanValencia: Brite.

Arlinda Valencia: Brite. Y que tenía una tienda, y ellos robaron . . .

Juan: ¡No!

Arlinda Valencia: ¿No?

Juan Flores: . . . Ahí llegaron los villistas.

Woman: Sí. Aha, okay.

The U.S. Cavalry chased after the men and exchanged fire, but some of the raiders escaped into the mountains in Mexico. Porvenir might have looked like a convenient scapegoat. A rumor spread that the villagers were harboring bandits—or had maybe even helped carry out the raid.

On a cold morning in January, a few weeks later, villagers in Porvenir awoke before dawn to loud knocks on their doors and men shouting outside. It was a group of Rangers from Company B. The Rangers told the residents of Porvenir that they were under suspicion and began searching the houses, as the families stood shivering in the dark.

When they had searched all the houses, the Rangers discovered just two guns: a Winchester hunting rifle, and a pistol that belonged to John Bailey, one of the only Anglo residents of the town. Nonetheless, the Rangers still took three men prisoner. They released them two days later.

For four days, the villagers lived like normal. But early on the morning of January twenty-eighth, the Rangers rode back into town, accompanied by a group of U.S. soldiers and some local ranchers.

Juan Flores and his family were awakened around 2 a.m. Across the village, families were forced outside. The Rangers began taking the men—including some of the boys, as young as sixteen.

The Rangers marched Longino and the fourteen other men down a path and out of sight. The women wept, and young children screamed; some of the villagers began praying. Suddenly, from where he stood in the village, Juan heard gunshots—dozens of them, again and again, and the sound of screaming.

Arlinda Valencia: And those men went in that night, and they killed fifteen men and boys. They left the wives crying for their husbands and for their children. And they went back home and got into bed with their wife, and kissed their children good night, and didn’t think anything of it. Who could be that way? I just don’t understand, how can they live with themselves, knowing that they left all these orphans?

As the sun rose, Harry Warren, Juan’s schoolteacher, arrived in town. And Juan joined his teacher in the grim work of identifying and collecting the dead.

Arlinda Valencia: I mean, he was one of the very few that actually saw all the bodies.

Jack Herrera: Really?

Arlinda Valencia: The next morning.

Jack Herrera: Did he talk about that?

Arlinda Valencia: Well, yeah. He said that they were all in pieces. Because after they shot them, they cut them up. And so, he said it was just horrific.

Some of the villagers stayed there and rebuilt their lives in Mexico. Arlinda’s relatives moved to Colorado City, Texas, three hundred miles away. Porvenir was abandoned almost overnight.

Arlinda Valencia: Their wives, I mean, come on. They had stuff in their homes. They should have had them come back and gotten all their stuff, but they didn’t. The wives said, “No, we won’t ever go back.” And so then, what do the soldiers do? They burn it down.

But even after that fire, and a century of wind and rain, some things still remained. Out in that desert, evidence of the horrors of Porvenir still sat, waiting for someone to find them.

I wanted to see that evidence for myself. And so, from El Paso, I drove through a rainy sunset, headed to an address in the small town of Alpine. I pulled up at an old saloon that looked right out of the 1800s. I didn’t see any lights on inside, but a dog was standing there and came up to me. She didn’t have a collar on. When I bent down to pet her, a man’s voice said, “Are you Jack?” It was David Keller, the archaeologist who excavated the massacre site.

David wore an outdoorsman’s shirt tucked into tactical-looking khakis. He led me into the saloon, which he explained had once been the Hotel Ritchey, which had stood there since the 1880s. We stood in a wood-paneled room over a heavy wooden bar.

David Keller: Now, this was the hotel that the cowboys came to—not the ranchers, not the high-heeled ones, but the blue-collar cowboys and that kind of . . .

Jack: On the range.

David Keller: They were the ones who came here. And the loading pens, the cattle-loading pens, were right across the street. [train horn blows] And there’s the train, right on time.

David told me about the night he learned of Porvenir. He didn’t quite understand it at first. He and some other archaeologists had gone to meet a West Texas historian named Glenn Justice.

David Keller: And we sat down and visited with Glenn, and that’s when he kind of started to reveal the story.

Glenn Justice told Keller and the archaeologists the story of Porvenir. And he took them to the exact site of where the town once was.

Years earlier, Glenn had gone with a documentary crew, who asked Juan Flores to show them where Porvenir had been. This was after Arlinda had finally pulled the story from her uncle Juan. Now David was being invited to come help examine the site.

David Keller: . . . And got out, and Glenn had some metal detectors. And fortunately, you know, because we’re archaeologists, we do our thing. We made a sketch map; we point-plotted the artifacts that we found; we took GPS coordinates. And that was the kind of stuff that hadn’t been done yet, you know.

Eventually, David decided to conduct a more detailed survey of the site. He pulled out a folder of detailed diagrams and maps and pictures of artifacts.

David Keller: So basically, what I want to say about this too, just in a broad sense, is that this was the first scientific investigation of this century-old crime scene. And it didn’t really dawn on me that it was a full-fledged massacre. But once we were out there on the site and doing the work, it started to kind of really sink in. I mean, these bullets that we were picking up off the ground had gone through human flesh. They had been used to kill people. And it was really an eerie feeling.

David remembers one he picked up in particular—metal embedded with something else, white.

David Keller: And when we saw that, I think I called all the other guys over, and we all just kind of stood there and looked at it. And, I mean, we were just kind of shocked and horrified by that.

Jack Herrera: Yeah.

He showed me the photo. The bullet was folded open like a flower.

Jack: Oh wow. Yeah. Oh, and is that—

David Keller: That’s the bone fragment.

Jack: Geez. Jeez. It’s horrible to look at.

David Keller: It is horrible to look at, when you think about it in the context. When we found this thing, it was just like, “Holy s—.” You know, it really brought it home.

The slow, methodical work of excavation continued. The execution site beyond that invisible village became a grid. Every bullet and every casing, a point on a map.

Things tend to move over one hundred years. But the Rangers had corralled the victims against a bluff to keep them from running—and against that same bluff, a century of dust had collected and kept the artifacts in place. On Keller’s map, I looked at the diagrams he had drawn of exactly where they’d found the bullets and shell casings.

David Keller: So what you’re looking at is the victim area and the shooting area.

Jack: Oh, my goodness, and where they stood. Wow.

David Keller: That’s what these circles represent. This is a concentration of bullets.

Jack: I’m getting gooseflesh from that. You can see where the firing squad was lined up.

David Keller: I know. It’s intense.

Then he told me about another discovery he’d made. Along with the .45-caliber bullets from Colt pistols—like the Rangers would’ve used—he found others. Casings from .30-06 rifle rounds, which the U.S. Cavalry would’ve used.

David Keller: And that was one element of the story that was never really part of the prevailing narrative. And so that was a kind of a huge “Oh, s—.” Soldiers don’t act on their own, you know what I mean? They don’t. They just don’t. They were told to do this by their superiors. And so what that implicates is that this was much more systematic and thought-out.

David said this didn’t prove that the military was involved, but it does show that military weapons were likely used.

This finding touched off a controversy when David announced it in 2016. Rangers boosters said maybe it was the soldiers, not the Rangers, who shot. The placard about Porvenir I saw in Waco at the Ranger museum implied that same thing.

Jack: When you say that implicates the military, it doesn’t let the Rangers off the hook.

David Keller: Oh, no, no. Absolutely not. The Rangers were known to—everybody knew the Rangers were there. They admitted to being there. The problem is, what was the military’s role?

The story before then went that the military rode out to escort the Rangers but didn’t take part in the executions. David says that’s not what this evidence suggests.

The next morning, I drove up to the university in town, the same one where David works. And I’m greeted by a familiar name on the sign out front: a huge brick sign reads, “Sul Ross State University.” Sul Ross—the former Ranger, hero of Pease River, Confederate general, and governor of Texas—and namesake of the state university in Alpine.

Jack Herrera: Victoria?

Victoria Contreras: Yes.

Jack Herrera: Hi, I’m Jack. . . . My colleague Zoe.

Victoria Contreras: Hi, nice to meet you.

Zoe Kurland: Nice to meet you too.

Sul Ross State University is the home of the Archives of the Big Bend. And I’m here to meet with its archivist, Victoria Contreras. She tells me that she just started here recently, and it’s a big job—there’s new stuff coming in all the time that needs to be cataloged.

Victoria Contreras: ’Cause I’ve worked with collections before, but not to this extent, and not to this extent of, like, I’m the sole archivist.

Jack Herrera: Yeah.

Victoria Contreras: Or, quote, unquote, “lone arranger.”

The Archives of the Big Bend are full of primary records from this tumultuous time in West Texas. Victoria told me their collection includes things that a lot of Texans would probably rather forget.

Victoria Contreras: How do I phrase this? Primary sources have a way of showing us the truth, whether we want to see it or not. And that can be uncomfortable for a lot of people. And especially for archivists who are trying to be a lot more honest about where we are and what we have, and what’s really happened in our area. That can get a little complicated.

Victoria led us into a reading room, and then back into the stacks.

Victoria Contreras: Okay. [door creaks] It’s sometimes a maze in here.

All around us were rolled maps and boxes stuffed with documents and photos. The air was thick with the smell of old paper. One of these old books is a journal of Harry Warren—Juan’s old schoolteacher, who had accompanied him back to Porvenir after the massacre.

In the Big Bend country, he’s remembered today as an important local historian. His notebooks dutifully record much of this place’s history from the early 1900s.

In the archives, I’m holding tall, slim pieces of lined paper covered in Warren’s handwriting.

Jack Herrera: And so, then, this is the earliest written account that we know about, I think, of what happened. I’m gonna do my best to read the [laughs], the cursive pencil handwriting.

Victoria Contreras: And if you need a magnifying glass or anything . . .

Jack Herrera: Oh, thank you. Yeah. I was one of the last years in school where they still taught cursive. [laughs]

When I started to read, I suddenly got goose bumps.

Jack Herrera: “On Saturday, January twenty-sixth, 1918, the state Rangers visited the small village of Porvenir . . .”

Warren writes about the Rangers first visiting Porvenir, when they had searched the houses. Then he writes about the night they returned.

Jack Herrera: “That day, the fated January twenty-eighth, 1918, sometime in the night, the Rangers again made their appearance at Porvenir, accompanied by four ranchmen: Buck Pool, John Pool, Tom Snider, and Raymond Fitzgerald, and twelve U.S. soldiers, with their captain, Anderson.”

It struck me, as I read this, the risk Warren must have been taking. He’s naming names.

Jack Herrera: “. . . While the Rangers went in and took the men and boys out from their warm beds, they making no resistance whatsoever. Having the men and boys in their possession, the Rangers started off down the river.”

He writes that the soldiers rode off, but then they heard the gunshots.

Jack Herrera: “One of the soldiers rode back, saw what the Rangers had done, cursed them, and told them, ‘What a nice piece of work you have done tonight.’ The killed were fifteen, as follows.” And then he lists the names of everyone who died.

In his account, Warren includes a detailed description of every victim. He says their names, who they were, who they’re survived by. I was struck by what loving detail he seemed to put into recording this event. And then Victoria told me something I didn’t know: she said that that morning Harry Warren saw the bodies, he recognized Tiburcio Jácquez, his wife’s. His father in-law. This event, his attempts to record what had happened—it was personal for Warren. And his work had a huge consequence.

Victoria Contreras: Part of it is, like I said, it’s probably the only account of what happened, and it’s one of those things that, based on the time period, based on the population in the area, I don’t think others would have been believed, anyway.

In other words, if not for this account by Warren—an Anglo settler who was friends with the villagers—the official history would’ve come down to the word of the women and children from Porvenir—if they had dared to speak up—against the Rangers’. And a cover-up was already underway.

Victoria Contreras: Ranger correspondence . . . this is folder seventy-three. Ranger J. M. Fox.

Right after Warren visits Porvenir, another account of the massacre is sent to Austin, this one by Ranger captain J. M. Fox. Fox was the commander of Company B, the Rangers who rode into Porvenir.

Jack Herrera: This is, this is pretty astounding. So this is a letter he writes on the thirtieth about what he describes as a skirmish on the night of the twenty-eighth. He’s lying about what happened at Porvenir. “I want to make report of a fight with Mexicans on the night of the twenty-eighth. Eight Rangers in company with four ranchmen was searching on the river and found several Mexicans . . .”

In this letter, a report to his boss, Fox claims that the Rangers were then fired upon by a group of Mexicans, and a, quote, “general fight” ensued.

Jack Herrera: And next morning, fifteen dead Mexicans were found there. He doesn’t even say, “We shot the fifteen dead Mexicans.” He just says, there was a bunch of shooting started.

Zoe Kurland: It’s all passive.

Jack Herrera: It’s all passive.

Fox’s telegram arrived in Austin just days after the massacre. An El Paso newspaper featured headlines about Mexican bandits and squatters who had been stopped in Porvenir. But the truth was set to come out: Warren’s account would make its way to the Texas capital. And, in Mexico, survivors of the massacre were telling their stories to soldiers and government officials. The Rangers were about to face the greatest existential crisis in their history.

[road noise]

Jack Herrera: Just passed a sign that said “Hazardous road; travel at your own risk; four-wheel drive only.” And reminding me that there’s no gasoline, no lodging, no food, no water. It’s gonna be a long fifty miles.

A little over a hundred years ago, this is the same country that a group of Rangers and soldiers rode through, headed for the same place I’m looking for. I wanted to see Porvenir for myself—whatever was left.

Jack Herrera: The landscape I’m driving through is beautiful. On each side of me, there’s low-laying brush and mountains that rise up, made angular from millennia of erosion.

I took some time walking along the creek, trying to walk out my frustration.

Jack Herrera: It looks like I’m less than half a mile away from Porvenir. And the Rio Grande has entirely jumped its banks.

It had been raining in the desert all week, and now the river was flooded. It seemed like the end of the road. But then I noticed something: a herd of cattle walking up the stream bank, on a trail they must have padded out themselves. There were some truck tracks, so I decided to try my luck.

Jack Herrera: I might as well give it a try. Wish me luck. Come on . . . got it! Woo!

I drove further along the river.

As I got to the edge of Porvenir, I felt the hair on my arm stand up. There was a break in the rain, and a huge ray of sun shone through the orange-and-purple clouds. Then I skidded to a stop in the mud. The road had disappeared into what looked like a huge lake.

I was struggling to comprehend what happened here—how to understand this violence, and what its legacy means for me, as a Mexican American.

I looked out at the floodwaters, covering the site of Porvenir. They reflected the mountains, the sky lit up with all the colors of the rainstorm. I thought: That’s what it’s like to look at this history. When I look at Porvenir, I see a murky outline of what was really there—and then my own reflection staring back at me.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login