Canada

Chinese Exclusion Act Shadows Linger In Canada A Century Later

Chinese Exclusion Act

On The 100th Anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Stories Of Isolation, Perseverance, And Bigotry Resound Through Generations In Canada’s History.

Yeung Sing Yew, Henry Yu’s grandpa, fell in love with a Chinese streamside lady in 1937. He had no idea that the harsh 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act would keep him from his family for over 30 years.

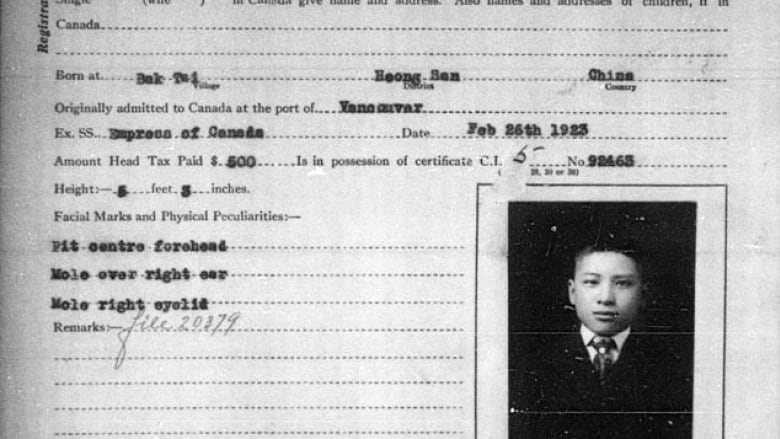

As an increase to the 1885 head tax on Chinese immigrants, the Exclusion Act restricted practically all Chinese immigration to Canada. Chinese people were denied the ability to vote, hold public office, own property, and labor-specific occupations in addition to financial constraints.

Anti-Chinese prejudice persists despite the end of overt discrimination. Asian Canadians still face bigotry, according to University of British Columbia historian Henry Yu. Economic challenges and municipal and provincial discrimination separated families after the Exclusion Act was repealed in 1947.

Yu’s family was separated by the Exclusion Act for years, which fostered his scholarly interest in legislating anti-Chinese racism. The Act shattered family structures and drove many Chinese men into “bachelor societies,” preventing them from starting children.

In 2006, Stephen Harper formally apologized to the Chinese Canadian community for the Exclusion Act. Landy Anderson’s grandpa, Ralph Kung Kee Lee, who paid the head tax and worked on the Canadian Pacific Railway, attended the event aged 106.

Some relatives feel the government’s apology and redress is inadequate. Gillian Der, whose great-grandfather paid the head tax, says money can’t fix past wrongs. She views it as a symbolic effort to hide structural prejudice that persists today.

Anti-Asian bigotry increased during the COVID-19 epidemic, complicating the story. Asian Canadians continue to endure racism, as a 2021 study found a 47% rise.

During World War II, Japanese internment added to Chinese Canadians’ feeling of being seen as perpetual foreigners due to historical scapegoating. This history of exclusion still affects this sense of otherness.

On the 100th anniversary of Chinese-Exclusion Act, Burnaby reviews past prejudice against Chinese Canadians. The Senate held a national memory ceremony to acknowledge and reconcile this tragic past, and the Chinese Canadian Museum opened in Vancouver.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau acknowledges the Exclusion Act’s ugly record and pledges to learn from past errors to create a more inclusive and equitable Canada. However, Henry Yu disputes the labeling of the Exclusion Act as a “mistake,” arguing that they were white supremacy-based actions that still haunt the present.

As the Chinese Canadian Museum opens and the country commemorates this melancholy milestone, the hope is that awareness and recollection will lead to a future without historical prejudice.

History Of Racism In Canada: The Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act shows racism’s legacy in Canada. The 1923 law banned practically all Chinese immigration, expanding the 1885 head tax. The Act saddled Chinese immigrants with debt and robbed them of fundamental rights, establishing a starkly unequal society. Chinese Canadians were deeply affected by institutional discrimination that denied them voting rights, public office, property ownership, and career possibilities for years.

Despite being abolished in 1947, discriminatory measures persist today. Decades of family separation drove many Chinese men into “bachelor societies,” denying them the ability to have children. This history of racism continues to shape Canada’s racial inequities.

Apologies And Redress: The Complex Path To Reconciliation

Stephen Harper apologized to Chinese Canadians in 2006 for the Exclusion Act’s harm. The government’s apology and reparations, although necessary, create difficult problems. The apology was seen by Landy Anderson’s grandpa, who had paid the head tax and worked on the Canadian Pacific Railway, but several families were dubious.

Gillian Der, a descendant of a head taxpayer, emphasizes that money cannot fix past injustices. Some see the reparations as an effort to ignore history and ongoing structural racism. How to confront past racism remains a significant concern for Canada as it works toward reconciliation.

Read Also: “Anti-Racism Group Forms To Monitor UK Police Amid Scandals”

Modern Challenges: Rising Anti-asian Racism

During the COVID-19 epidemic, anti-Asian prejudice increased. Asian Canadians continue to endure racism, as a 2021 study found a 47% rise. Some Asian Canadians struggle with internalized racism, like Toronto lawyer Kate Shao. Shao’s father tried to adapt by denying his Chinese background in Winnipeg, but pandemic-related scapegoating defeated him.

The rise in anti-Asian prejudice on the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act highlights the need to confront deep-seated biases. Asians have been blamed for social issues since Japanese incarceration, contributing to institutional racism. An inclusive approach to fighting racism in Canada is needed more than ever.

Recognition, Remembrance, And Progress

As Burnaby reviews historical prejudice and the Chinese Canadian Museum opens, Canada confronts its history to create a more inclusive future. Justin Trudeau’s battle against bigotry and intolerance acknowledges previous errors. The real problem, Henry Yu says, is acknowledging that the Chinese Exclusion Act was planned, purposeful, and founded on racial racism.

The 100th anniversary of Chinese-Exclusion Act is a sobering reminder of Canada’s prejudice and a call to action for equality. Recognizing and remembering past errors is intended to liberate Canada from historical prejudice.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login