Illinois

Black women make up one in 4 crime victims in Chicago

Editor’s note: This is the first installment of Investigating Injustice, a series by the CBS 2 Investigators examining the disparate impact crime has on Black women in Chicago. If you were impacted by these types of crimes and would like to share your story, you can contact us here.

Crime.

It’s all Chicago talks about.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, headlines of violence and mayhem returned to the public gaze. Crime stats of those who were carjacked, robbed, shot or killed gave an overwhelming sense of a society unmoored.

But the spectacle of crime can evoke fear, often overshadowing those who are truly affected: the victims.

Victim identities are rightfully protected from public view, but data about a person’s race, sex and age can tell a great deal more than monthly figures of violent crimes.

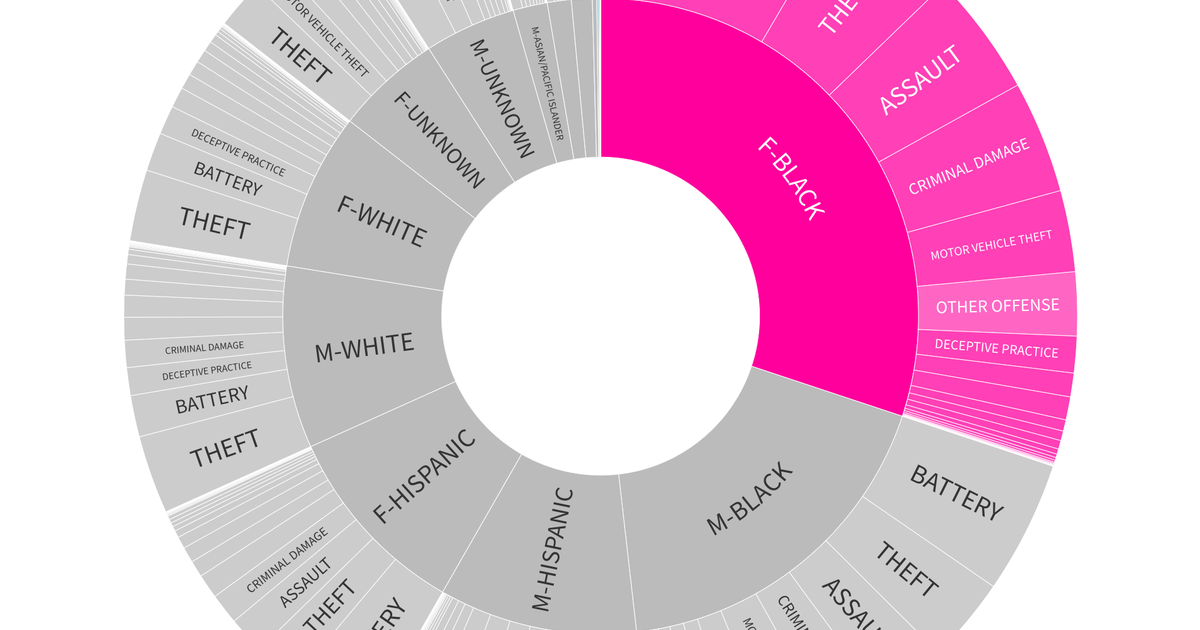

Through public records requests, CBS Chicago obtained police data that contains the victim profiles for every reported incidents in the city over the last two decades, accounting for more than 8 million victimizations, and one group consistently held the burden of crime: Black women.

In 2022, there were more than 26,000 violent crimes and more than 212,000 non-violent crimes in Chicago ranging from shootings and robberies to retail and motor vehicle theft, affecting roughly 260,000 victims.

About 67,000 people, or 25% of crime victims were Black women, according to a CBS Chicago analysis of police data.

Black women only make up 16% of the city’s population, but over-index in most categories of crime, accounting for 1 in 4 victimizations. That ratio is more pronounced – about 1 in 3 – when accounting only for reported crimes with race data, and excluding crimes without clear victims such as retail theft, FOID card violations or narcotics arrests.

The resulting analysis becomes the closest accounting (short of actual names) of who is directly affected by crime in Chicago.

“It’s not fair. To have to navigate through life knowing that you’ll potentially become a victim of a crime primarily because of your race and your gender… it’s not fair,” said Tonia Thomas, a 27-year-old resident on Chicago’s West Side.

Thomas’s views on crime against Black women are personal as she is a sexual assault survivor.

“I’m still angry that the thoughts don’t go away. What happened to me, it won’t go away.”

Thomas lives in the Austin neighborhood and works as an assistant store manager. At her home, she recounted being assaulted at a friend’s party in 2021.

“Some days, I could go maybe a week without thinking about it. But then I have that one random day… I’m driving home from work, or I’m driving somewhere, and suddenly, my mind just kind of goes off. It’s there reminding me.”

There were about 1,600 sexual assault victims in 2022, and Black women made up about 40% of the victims, according to victim data.

That trend held true for most violent crimes in the city.

Black women were the most victimized group in Chicago last year, accounting for 35% of assaults and 38% of batteries. Black women also accounted for 34% of 146 kidnappings and half of the 19 human-trafficking victims.

Black women were also over-indexed in non-violent crimes last year, accounting for nearly a quarter of property thefts and 28% of motor vehicle thefts, where race data is available.

The data show the challenges faced by women in high-crime areas.

“I wish I could say I’m surprised, but I’m not,” said Geneva Brown, a professor of criminology at DePaul University.

She said a combination of policing issues and government policies have contributed to Black women being victimized, such as working requirements for food assistance.

“[There’s] the perception and demonization of poverty and the feminization of poverty. So women have to work and so they get jobs where they can, sometimes it’s third-shift. Not everyone’s able to work in an office.”

“They’re targets because they’re easy prey,” Brown said.

“Because you’re in economically unstable times, and who is out on the streets? Who’s the most vulnerable? Officer Preston… was on her way home at 1:40 in the morning, and she was the target of a robbery,” she said, referring to Chicago police officer Aréanah Preston, who was murdered on May 6.

Brown said Black women are disproportionately working third-shift jobs and are in communities lacking a middle class and economic foundation that would deter this type of behavior.

“They’re out at times when there is not a lot of police presence…they’re out there alone on the bus stop, or they’re riding the Red Line alone.”

The data does support some of Brown’s assertions. Of the 455 victims assaulted on CTA buses, bus stops, trains and stations last year, Black women were the hardest hit, accounting for 181 victims, or 38%. Black men accounted for 30%, or 134 victims. Black women also accounted for more than half of the 27 sexual assault victims on the CTA.

“Personally, I mean, I love being a Black woman. I don’t have any issues. I go into the world and I feel respected,” Thomas said.

“But in terms of the fear, never knowing what’s going to happen to you, they’ll call it hypervigilance. But it’s not. It’s realistic.”

That reality is reflected in data. Black women were the most victimized group in Chicago not only last year, but almost every year for the last two decades.

“[There are] stereotypes that black women are not truly being victims because of being aggressive, being masculine, over-sexualized,” professor Brown said.

“All those things can take away from what may be considered the ideal victim. Consider a middle-class white woman versus a poor black woman. That’s like the idealized victim versus a working-class Black woman who may have to adopt a persona to protect herself. And maybe that persona is perceived as making her less vulnerable, less a person who is receptive towards the receiving services, or being seen as a victim.”

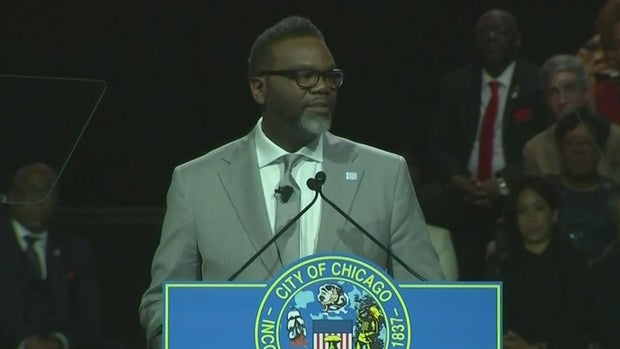

Addressing the root causes of violence such as poverty, is an issue that got Mayor Brandon Johnson elected in April. His opponent, former Chicago Public Schools CEO Paul Vallas, ran on a campaign of addressing crime with tougher policing.

Johnson spoke of addressing these issues during his inauguration last month.

“We don’t want Chicago that has been overwhelmed by the traumatization of violence and despair that our residents felt no hope or no choice but to leave.”

On that point, Johnson and Brown from DePaul University would seem to be in agreement.

“You [had] the strong community that existed in the ’80s, or even before that in Chicago, that’s gone,” Brown said.

“100,000 Black people have left the South Side of Chicago alone, probably within the last 10 or 20 years. You have the middle-class community leaving Chicago in droves, and it leaves poor people. It also leaves people being preyed on and unfortunately, those who are the most targeted are Black women.”

Applying demographic data to Chicago’s crime victims allows for new questions and challenges assumptions on who’s affected by crime.

The data reveal that most common the experience Black and Latino residents have with crime in Chicago are batteries, while white residents experience crime mostly through property theft.

The data can reveal who’s getting assaulted on trains and whose KIAs were stolen, but also reveal some not so obvious trends, such as who suffers from domestic violence? How are seniors impacted by crime?

The most common crime affecting seniors was theft, and Black women were the most represented group in that category, while white women over 65 were the most represented group with deceptive practices, associated with identity thefts and scams.

When focusing on crimes affecting those under the age of 18, a clearer picture can emerge on violence against children in Chicago.

In 2022, for every white girl who was a victim of battery, there were 14 Black girls who were battered, according to an analysis of victim data.

Similar disparities existed for middle-aged and senior women, despite Chicago’s demographic makeup being roughly the same for white, Black and Hispanic residents.

“I was being bullied in high school, stalked by an ex in high school, and I didn’t really have any safe place to turn at that point,” said Aaliyah Phillips, who lives in Chicago’s Austin neighborhood.

She attended Little Village High School in South Lawndale.

Now at 26, Phillips works as a program director for a non-profit.

She recounted her experiences at school, where she fell victim to abuse.

“I ended up dating this young man… And when I wanted the relationship to be over, because I saw he had violent issues. He was very violent,” Phillips said.

“He was very mentally abusive. He begins to stalk me, he learned my location of how I walk home. He will steal pictures off my social media… All of that was very traumatic.”

Black women are the most stalked victims, according to victim data. Last year, there were more than 200 Black women stalked, accounting for almost half of the 437 reported victims. Hispanic women accounted for 17% of stalking victims, while white women accounted for 15%.

Phillips said she was punched and choked during an argument and had to bite him in self-defense.

“It was very common. I saw a lot of teenagers my age going through that… fighting the person they were dating, so it had become normal to me.”

This normal has been the reality of Chicago’s crime for years. Homicides, shootings and robberies garner the bulk of attention to crime. In 2022, there were more than 3,500 people shot, 638 of them fatally. Black men accounted for 65% of the city’s shootings. Black women accounted for 16%.

But for almost every other crime category, Black women accounted for the most victimizations, an issue that’s not often at the forefront.

“My reaction unfortunately is not unnerving. Growing up as a Black woman, I saw a lot of those statistics within my own family,” said Gabrielle Molden-Carlwell, a trauma therapist that focuses on recovery from sexual assaults.

“It’s disheartening. It causes self-doubt because something must be wrong with me.because these women that are survivors of crime whether it’s violent or not, are complex trauma survivors.”

Molden-Carlwell said more resources are needed. She equated the need for therapy services to that of food deserts, calling them therapeutic deserts.

“I feel like this is just as bad as the war on drugs, like everything [got] shut down for that, but what about these crimes?” Molden-Carlwell asked.

“Whether they’re violent, non-violent, sexual, where’s the support? Where’s the campaign?”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login