I.

The land had been theirs since long before any of them could remember. As a child in the fifties, Lawrence Smith grew up playing in its spring-fed creek and riding in a mule-drawn wagon driven by his father, who grew peanuts, sweet potatoes, and watermelons in its loamy soil. Once he’d grown into a man, Lawrence used its pasture for raising cattle and hogs, some of which he had butchered for his freezer, alongside the venison from deer he regularly shot as they bounded across its 36 acres. Lawrence tended the land for decades, as his father had before him.

But then the twin cities of Bryan and College Station, ten miles to the northwest, saw rapid growth. About twenty years ago land values began to greatly increase, which changed everything for the rural acreage Lawrence’s ancestors had held since a decade after the Civil War. Few understood this better than he did, after he was taken to court in the aughts by a cousin who tried to lay claim to the family tract. When his nephew told him, in the summer of 2012, that he was being sued by a real estate investor, Lawrence’s first thought was “Not again.”

His nephew, a College Station police officer named Brad Smith, found out about the lawsuit by accident. A colleague told Brad that someone was challenging her ownership of a small parcel she’d recently bought near the Smiths’ property, in an area known as Petersburg Settlement. She eventually decided to sell rather than continue to fight in court, which likely would have cost her more money than the land was worth.

Brad wondered whether the same man who had sued her, Curtis Capps, had also taken action against his family’s land. Sure enough, by searching county judicial records online, he found a case called Curtis Capps v. The Estate of Anna Hackney. Anna Hackney was Brad’s great-grandmother, who had left behind the tract in Petersburg Settlement. So he called his uncle Lawrence, then 65 years old and newly retired from his job as a department manager at a bookstore on the Texas A&M University campus.

The Smiths’ tract was heirs’ property, land handed down from generation to generation without the use of wills. This form of ownership is not unusual in Black communities, where access to attorneys—and often the funds to pay them—has historically been scarce. Much of the acreage held by Black families in Brazos County and throughout the South is heirs’ property, a legacy of the region’s poverty but also of the lack of trust in white attorneys and the court system during the Jim Crow era.

Heirs’ property tends to become more and more diffuse as new generations have children. Eventually any individual heir may own only a tiny percentage of the land, known as an “undivided interest,” not unlike holding a few shares of stock in a company. Lawrence’s cousin’s suit against him had demonstrated that heirs’ property was a tenuous form of ownership. But Curtis Capps was no rogue family member—he represented something far more formidable.

In the lawsuit Brad discovered, Capps was claiming ownership of almost the entire Anna Hackney tract. The opening pages listed sixteen heirs as defendants, but Lawrence’s name, strangely, was not among them, even though the property’s tax bill was mailed to his address every year. Lawrence, who has a compact stature and an easy laugh and is rarely without a Texas A&M hat atop his close-cut gray hair, knew almost everyone in the extended community of Petersburg Settlement landowners, most of whom are related in some way.

Reading through the list of defendants, he recognized some names, but others were unfamiliar—distant cousins who had moved away years ago or never lived in Brazos County. One man had a Delaware address; others were from Kentucky, Pennsylvania, or Tennessee. Why sue these people, Lawrence thought, and not the man who had dutifully paid the property taxes and lived in Brazos County all his life? The rest of the suit was a long and convoluted account of the ownership history of Hackney’s land, referencing deeds, surveys, and transactions from the distant past. Lawrence couldn’t make heads or tails of it, and he strongly suspected that he wasn’t meant to.

When Lawrence and his nephew showed up for a hearing on the suit, the judge recognized Brad from a criminal case in which he had once testified. “Officer Smith, what business do you have in court today?” he asked. Brad introduced his uncle to the judge and explained that he was an heir to the property at issue, even though he had not been named in the lawsuit. At the plaintiff’s table, a ruddy-faced man in his late sixties with elfin features and thinning hair turned and stared at the Smiths. “Mr. Capps,” the judge said, “it looks like we had better postpone until you get this sorted out.”

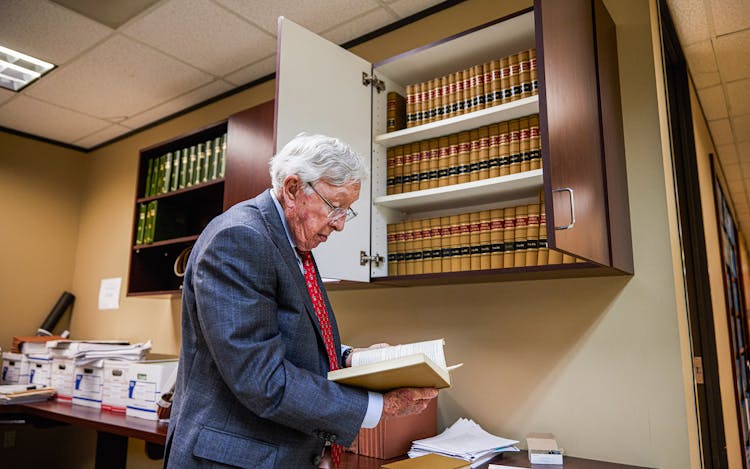

A few weeks later, Lawrence and Brad met Capps in Bryan, at the office of his lawyer, Bill Youngkin. A former yell leader at Texas A&M, Youngkin is roughly the same age as Capps, but with a more imposing carriage and a salesman’s easy manner. Youngkin has been a top real estate attorney in the Brazos Valley for decades. At the Brazos County courthouse, he is as well known as any judges he argues before, few of whom can match his experience or longevity. (Lawrence calls him “the tall hog at the trough.”)

Capps’s manner was brusque and, to Lawrence’s mind, arrogant. He had already secured most of the Anna Hackney tract as a result of a recent judgment in another lawsuit and was now suing Lawrence and his fellow Hackney heirs to clear up his title to the land. According to Capps’s research at the county clerk’s office, Hackney never owned as much of Petersburg Settlement as her heirs thought she did, and many of the deeds created in conjunction with the tract over the years were faulty. He offered $3,000 for Lawrence’s share of the land, plus $10,000 more if he would persuade the other heirs to sell their shares. “I’m going to get it all eventually anyway,” he said.

Lawrence was insulted. He had long assumed he’d sell someday; real estate agents perked up whenever he mentioned he owned property southeast of College Station, where new subdivisions—some with million-dollar homes—had been creeping steadily toward Millican, the old railroad town where Lawrence was born. Land in that part of the county was going for at least $5,000 an acre and in some cases twice that, which meant his family’s parcel was worth as much as $360,000. He knew he would have to share any sale proceeds with dozens of other heirs; still, he felt that his taking care of and paying taxes on the land had to count for something. “I wanted to get enough for it that all of us heirs in there can go down and buy a pickup truck without being broke,” he said later. Capps was offering him peanuts.

Lawrence didn’t have the money for a lawyer; he’d already spent thousands contesting his cousin’s lawsuit. That litigation had ended with roughly a third of the land in his cousin’s name, and Lawrence wasn’t expecting a favorable outcome this time either. Indeed, in May 2013 the judge ruled in Capps’s favor, finding that Lawrence and his fellow heirs owned only 3.6 acres of the 36-acre tract that had been in their family for generations.

It got worse. Capps asked the court for what’s known as a partition, a proceeding in which a tract is apportioned among its various owners. In this case, the judge determined there was no fair way to divide the 3.6 acres among Smith and his fellow heirs and instead ordered it to be sold, so that each heir could be compensated in cash. Capps then purchased the 3.6 acres himself, completing his takeover of the Anna Hackney tract. The district clerk’s office sent Lawrence a check for his share of the sale proceeds: $635.

Just like that, his land—representing a significant portion of his family’s wealth—was gone. Lawrence wasn’t alone. As he came to understand in the years that followed, Capps and Youngkin had targeted heirs’ property all over the Brazos Valley. Black land ownership was under siege.

But some of Lawrence’s neighbors in Petersburg Settlement decided to fight back, kicking off an eleven-year legal saga that has spawned half a dozen lawsuits, accusations of fraud, and a decision from the Supreme Court of Texas—along with a mountain of paper at the Brazos County courthouse. Those pages contain a road map for how Capps and Youngkin operate—as well as a troubling indictment of the justice system.

II.

Curtis Capps began his real estate career as a title examiner, a researcher who digs into the history and accuracy of ownership records to ensure that there are no surprises when properties change hands. In small-town county courthouses, he honed his trade by sifting through deeds, many of them recorded in longhand generations ago, when the Brazos Valley was sparsely populated cotton-farming country. He discovered there was gold in those dusty records, and he soon began building his own portfolio of real estate. Since the seventies, Capps has bought and sold hundreds of parcels—covering tens of thousands of acres and likely worth millions of dollars—in Brazos and in neighboring Robertson County. Like many investors, he specialized in “courthouse steps” auctions, buying real estate seized for unpaid taxes and flipping it for a profit.

Capps, who lives outside of Sutton, about fourteen miles northwest of Bryan, is a fixture in the records room of the Brazos County clerk’s office and at the tax office. There he spends hours conducting his research, looking for his next opportunity. He strikes an avuncular figure, known for bringing doughnuts for the mostly female staff at the tax office. The county government is a modern operation these days, but Capps, who does not own a computer, is still very much an analog person. “I know how to check a little title, but I’m not an attorney,” he says.

In fact he is something of a savant in the arcane world of real estate records. By virtue of a defect he claimed to have discovered in an 1881 tax deed, Capps once managed to persuade the Robertson County Commissioners’ Court to grant him a four-acre parcel that some of his neighbors had owned for more than 95 years. In a legal brief, Steve Rodgers, a veteran Bryan attorney who represented the neighbors, called Capps’s methods “devious, calculating,” but later grudgingly admitted he is skilled at using title documents to get what he wants. Youngkin comes up with the legal strategies, but the research—such as the befuddling history of the Anna Hackney tract—is all Capps.

That Capps and Youngkin have long targeted heirs’ property is not a secret, according to Judge Travis Bryan III, who shared a law office with Youngkin in the early aughts. Bryan has known Capps since they were both schoolkids in the sixties. “Curtis is a title guy. He’s sharp about defects in title, how to take advantage of things that appear on the record and the public doesn’t know about. And Bill was his lawyer. And they saw an opportunity to make money,” said Bryan, a descendant of William Joel Bryan, the prominent plantation owner for whom the city is named. “It’s not just ‘I’m a lawyer and he’s my client.’ They’re actually in it together.”

Less well known was the scope of their undertaking. Through public records and interviews with courthouse officials, local attorneys, and heirs who have lost property, Texas Monthly has, over the past five months, examined two dozen cases in which Capps—represented by Youngkin—has sued to acquire heirs’ property. The lots in these cases, all of which have been filed since 1999 in either Brazos County or Robertson, range in size from a few acres to more than a hundred. In some cases, Capps took ownership of entire tracts; in others he forced a partition and wound up with a substantial portion. In a few cases he came away empty-handed. Collectively, the land involved comprises more than a thousand acres, and the total dollar value of what Capps has acquired, while difficult to calculate precisely, is certainly in the millions.

Because Capps so often targets heirs’ property, much of the land he seeks to acquire is Black-owned. After the Civil War, a considerable number of the formerly enslaved settled in the bottomlands of the Brazos and Navasota Rivers, which form a broad V that borders Brazos County. Bryan and College Station are ringed by these so-called freedom colonies—many with little left besides a historic cemetery amid empty acreage, much of it heirs’ property.

That land has become more and more valuable. Over the past twenty years, the population of Brazos County has increased by more than 50 percent, to 242,000, driven by the growth of Texas A&M and by families relocating from the Houston area, drawn by the promise of good schools and the bucolic countryside. Old neighborhoods in Bryan and College Station are gentrifying, but the effect has been most pronounced in rural areas, where land is rapidly being cleared for new subdivisions. Pasture that once went for $1,000 per acre is now worth five times that or more. Robertson County, to the north, has also experienced significant growth and rising property values. The result has been a modern-day land rush, with Black-owned property at the center of the frenzy. According to data collected by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, from 2002 to 2017 (the most recent year available), the amount of land under cultivation by Black farmers in Brazos County fell by 2,377 acres, or 21.3 percent. (For comparison, total county land under cultivation fell by only 7.6 percent during roughly the same period.)

Brazos County is not an outlier in this respect. According to a 2022 study, the amount of land under Black ownership in the seventeen states that are home to almost all of the nation’s known Black-owned farms dropped by about two thirds between 1917 and 1997—a decline representing property with an estimated value today of $326 billion. How much of that was sold willingly and how much was lost involuntarily is difficult to quantify, but there is no question that the tenuous nature of heirs’ property, which makes up what’s estimated to be more than one third of Black-owned land in the South, continues to erode Black wealth. The USDA has identified heirs’ property as the leading cause of involuntary land loss for African Americans, making it a major contributor to the wealth gap between white and Black America.

“It’s such a problem that we can’t even identify the scope of it,” said Andrea Roberts, a professor at the University of Virginia and director of the Texas Freedom Colonies Project, which she began as a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. The project aims to map every historic freedmen’s community in Texas, part of a larger effort to protect historic Black settlements and assess the magnitude of Black land loss in the South. What may appear to be just empty acreage along a rural road is often the hub that holds a widely dispersed Black family together. “This is where their critical spiritual and financial assets are, which they’re handing down to future generations,” Roberts said.

In the Brazos Valley, much of that land has been lost to the work of just two men.

III.

A typical Capps case begins with contacting an heir, frequently one who is unaware that they have inherited an interest in the targeted tract. Carolyn Waldon, a retired Bryan ISD counselor, said a representative of Capps met with her elderly mother-in-law, Bertha, in 2016, inquiring about fifty acres not far from Millican. Bertha, who had been diagnosed with dementia, had no idea she was an heir to the property. “She was told her portion of the land wasn’t even big enough to park a car on,” Waldon said. Bertha signed away her interest on the spot for $1,200. Waldon worried her mother-in-law had been taken advantage of.

Brad Smith has heard similar stories from members of several other families, who received letters from Capps threatening suit over Petersburg Settlement land. “Capps tells you, ‘You know, your uncle has already sold his interest, and your cousins have all sold. We’ve got your check here too, and we just need you to sign these papers,’ ” he said. “You’re talking about someone who may only have $1,000 in the bank, and here is someone offering them a few thousand for some land they might not have seen since they were a child. It’s like they won the lottery.”

Irma Jones, whose mother was an heir to property near Millican, did not even know her family was being sued until the case was ready to go to trial in 2014. Plaintiffs in heirs’ property suits are required to serve notice on every heir they can locate. Heirs that can’t be found—along with so-called “unknown heirs”—can instead be notified through a newspaper ad. In Brazos County, that usually means the Bryan–College Station Eagle—a publication with a venerable pedigree but limited reach. Jones, who lives in Alabama, was alerted to her case by a distant cousin. She discovered mistakes in a family tree prepared for the suit that purported to list all of the heirs; her mother had been left off, and at least one name was not a relative at all. The judge required Jones’s mother to prove her relationship to the family in order to be let into the case. “But did everyone else on their list have to do the same?” Jones said.

When a court orders heirs’ property to be divided, Capps seemingly has a knack for getting the most accessible portion. Geraldine Hester owned an undivided interest in 27 acres not far from the community of Wellborn, just south of College Station. Capps acquired an interest from other heirs and sued to force a partition. When the court apportioned the land, Capps ended up with the parcel closest to the road on which the tract sat, which meant that everyone else had to access their property through his.

“Landlocking” properties is a tactic that Capps and Youngkin use to induce other owners to sell, according to Bryan attorney Hugh Lindsay, who has faced the pair in a number of heirs’ cases. “They beat the people to death with those [suits],” said Lindsay. The 83-year-old was less reticent than some in his assessment of how Capps and Youngkin get what they want in court. “Some of it is experience, and some of it is—if you don’t mind me saying so—out and out bullshit,” he said. “I have seen them treat the truth a little roughly in some of these cases and try to ride right over people.” (Youngkin told Texas Monthly he and Capps do not employ such tactics.)

In Hester’s case, the court required Capps to provide access to the neighboring parcels, but her daughter, Faith Holland, still felt her mother had been cheated by being left with only twelve acres. “She paid the taxes all those years, and so that’s not fair,” said Holland. “That’s our family’s heritage and legacy that he took.” Capps offered to buy Hester’s land for $90,000. Holland eventually sold it for three times that, but not to Capps, whose name by then had become something of a dirty word in the Black community, the subject of grim whispering in church and in the aisles of H-E-B.

Royce West, a well-known attorney and state senator from Dallas, is representing a Brazos County landowner in a case involving Capps. West knows the issue well; he authored a bill in 2017 that reformed the way judges handle heirs’ property cases. “It’s a safeguard against unscrupulous investors coming in and just taking all of the property,” he told Texas Monthly. Among other provisions, the legislation ensures that if one heir (or purchaser of an undivided interest, such as Capps) sues to force a sale, the remaining heirs have the right to purchase the plaintiff’s interest at a fair market price before the entire property can be put on the market. It also strongly encourages judges to give preference to partitioning instead of a forced sale. West said he’s concerned that not enough heirs’ property owners are aware of the law’s protections. “There are families that have had land in their family for a hundred and fifty to two hundred years, and they want to hold onto it,” he said. “That’s the very reason I did this.”

Capps’s unflagging endeavors have also become a source of consternation for some Brazos County authorities, according to David Fitz, director of property information for the appraisal district. When someone presents a deed purporting to represent his purchase of an undivided interest, Fitz’s staff has no way of determining whether the seller is actually an heir to the property in question or how much of it he or she has the right to convey. They can’t record that deed. “We don’t have a paper trail,” he said. Fitz told Texas Monthly that years ago his office began setting aside such deeds filed by Capps, unless he also brings along a court judgment to back up his claims. The resulting pile has grown quite large. “We’ve got a stack of papers that’s probably eight inches thick,” Fitz said.

Like other county officials, Fitz was reluctant to say more on the record about Capps, who is known to be uncommonly litigious. In addition to the heirs’ property suits, he has filed dozens of unrelated actions over the years. He has sued the City of Bryan multiple times, along with contractors, neighboring property owners, and sundry other defendants in small-claims court. He sued the Texas A&M football booster club over a price increase for his lifetime season tickets. He sued his sister over the division of their mother’s estate. (At issue: how to divide 336 acres she had left behind.)

But it’s the heirs’ property suits that Capps and Youngkin have down to a science. They are not the only ones acquiring land this way in the Brazos Valley, but their track record is, by all accounts, unmatched. Or it was, until the pair set their sights on Petersburg Settlement.

IV.

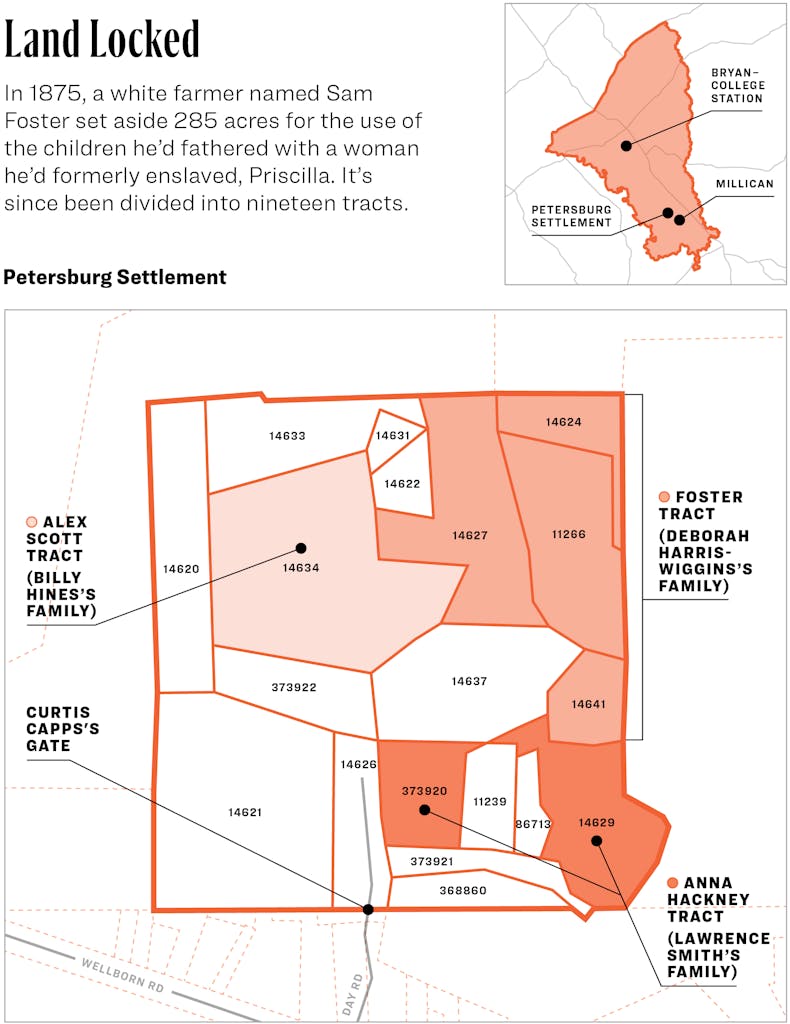

Petersburg Settlement holds a cherished place in the annals of Black land ownership in Brazos County. In 1875 a white farmer named Sam Foster set aside 285 acres not far from Millican for seven of his children, each of whom he had fathered with a woman he’d formerly enslaved, Priscilla. Some of the children settled on the land, where they farmed row crops, tended livestock, and raised their families.

Deeds were eventually issued to some of Priscilla’s heirs, making their ownership official. But none of the original deed holders left a will, which meant the land became heirs’ property, and its legal status got steadily murkier. Over the years it was divided into nineteen tracts, including the acreage that Lawrence Smith and his family inherited. These divisions were made either informally or, in some cases, through the issuance of deeds, not all of which described the tracts consistently or in sufficient detail. There are now hundreds of known heirs to the land Priscilla Foster’s children once farmed, though nobody lives there anymore.

In 2007 the Brazos County tax assessor filed suit to recover about $51,000 in unpaid taxes on a single forty-acre tract in the southwest corner of Petersburg Settlement. Two heirs paid $9,800 to forestall foreclosure by the county and sent demand letters to the other owners, asking each to pay them for their fair share of the bill. The letters came from Buetta and Rajena Scott, a mother and daughter in Oakland, California, who were related by marriage to one of the original deed holders in Petersburg Settlement. The pair hired Bill Youngkin to initiate what’s known as a Chapter 29 suit, claiming ownership of the delinquent tracts as compensation for paying their fellow heirs’ share of the tax bill.

But that wasn’t all the suit demanded: the Scotts argued that the taxes they had paid entitled them to a substantial interest in almost every tract in Petersburg Settlement, not just the forty acres the county had tried to seize. This included Lawrence Smith’s land and other parcels on which no delinquent taxes were owed. The rationale for this claim came from the Scotts’ silent partner: Curtis Capps. Because the county’s description of the forty acres was nebulous (“about the worst title job I have ever seen,” Capps would later call it), he reasoned that Buetta and Rajena were paying back taxes on the entirety of Petersburg Settlement.

The case, styled Buetta Scott and Rajena Scott v. The Unknown Heirs of Alex Scott, et al, was adjudicated in a 2010 hearing at the Brazos County courthouse. Youngkin appeared for the plaintiffs, who did not attend in person. Neither did the vast majority of the defendants. (Lawrence Smith, for his part, had no idea this case had even been filed.) Only one heir hired a lawyer to fight the suit. That heir was a preacher from Houston named Billy Hines, who owned an interest in 45 acres of Petersburg Settlement known as the Alex Scott tract.

Before formal arguments began, Youngkin proposed a settlement with Hines: If Buetta and Rajena gained an interest in the Alex Scott tract, they would agree to deed that to Hines, so that the Alex Scott heirs could continue to own and enjoy their 45 acres as they always had. In exchange, Hines would give up any claim he might have to the rest of the Petersburg Settlement land. Hines agreed, and Youngkin read the deal into the court record, making it official.

With Hines out of the way, Youngkin’s only opposition was an attorney ad litem, a lawyer appointed by the court to represent any heirs who may have had a claim on the land but could not be located. But that attorney, Michael Calliham, raised no objection to the lawsuit’s claims. (Calliham died in 2021.) Nor did he speak up when a real estate appraiser, under questioning from Youngkin, testified that the forty acres the county tried to seize was worth only $500 per acre because it had no public access, and that the rest of Petersburg Settlement was worth nothing because of the considerable title issues that would accrue for whoever took possession of it.

No one in the court that day mentioned that Petersburg Settlement’s various tracts were collectively appraised at more than $1.2 million by the county at the time. Even that figure likely understated the land’s value. As one of the largest undeveloped parcels between College Station and Millican, the entire 285 acres would likely be worth millions to a subdivision developer.

Later that afternoon Judge J. D. Langley found for the plaintiffs. His order effectively awarded Buetta and Rajena outright ownership of 59 acres, plus a significant share of another 212 acres, instantly giving the pair a commanding interest in almost all of Petersburg Settlement. Because of the appraiser’s testimony, meanwhile, the judge ordered that Buetta and Rajena need not pay any compensation to any other heirs for the land they’d been awarded, as would ordinarily be required in a case such as this. (Langley, who has since retired, told Texas Monthly he did not recall the case.)

Heather Way, a UT-Austin law professor whose work has contributed to heirs’ property reforms, said recently that Langley’s ruling to award Buetta and Rajena interests in parcels on which no taxes were in arrears seems “very troubling.” But she understands how the appraiser decided that most of Petersburg Settlement had no market value, given the tiny size of other undivided interests and some of the wording in Chapter 29 of the state property code. This “ludicrous” outcome, she said, points to the need for changes to the statute. “There is unfortunately validity in where the court came out on that issue.”

With a suit that runs just eight pages long—roughly six of which are taken up by a list of heirs—along with $9,800 in back taxes and a brief appearance in court, Youngkin had wrested hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of property from dozens of families who had held it, in some cases, since Reconstruction. Within two months of Langley’s ruling, Rajena Scott began deeding all of the property to Curtis Capps.

In order to sell the land himself—most likely to a subdivision developer—Capps needed clear title to all of it, eliminating any other claims that might stand in his way. So he filed a series of suits against the heirs of several large tracts within Petersburg Settlement. These included his 2012 suit against Lawrence Smith and the other Anna Hackney heirs, which resulted in the judgment he anticipated. Another such action—concerning 63 acres known as the Foster tract—did not.

V.

Nettie Clay was the type of woman who read the newspaper thoroughly from front to back, which is how she came to spot her name in the Bryan–

College Station Eagle in the summer of 2012. A classified advertisement informed her that she was being sued by Capps. Clay was one of the last descendants of Priscilla Foster to live in Petersburg Settlement, though she had moved off the land some years before. She called her sister Nancy, who in turn called her daughter, Deborah Harris-Wiggins, a 45-year-old program specialist at the Texas Juvenile Justice Department in Bryan.

Perhaps because Harris-Wiggins has two master’s degrees, or perhaps because of her stature—she stands six feet four inches—her extended family tended to defer to her. She convened a meeting to discuss how to deal with the lawsuit. Like Lawrence Smith, Harris-Wiggins had no idea a portion of her family’s land had been deeded to Capps thanks to the suit filed by Buetta and Rajena Scott.

Harris-Wiggins had always known about her West Coast relations; her grandmother had seven siblings—two sisters, who had both stayed close to home, and five brothers, who had all moved to California. Harris-Wiggins had grown up with her great-aunts and their many children, a host of cousins now spread around Texas. Every year they gathered on the family’s land for a reunion, where they listened to stories about the history of Petersburg Settlement from the older generation. The family decided to pool their resources and hire Steve Rodgers, the attorney who had crossed paths with Capps in the case against his neighbors. “We knew that other families had given up and sold to Capps,” she said later. “But we felt that the Lord would sustain us.”

The case was heard in the summer of 2013 in the court of Judge Travis Bryan III. It was Harris-Wiggins’s first time seeing Capps in person. “Just strutting like the big rooster in the henhouse,” she said later. She had never met Youngkin either, but she discovered that they had a connection: Youngkin’s wife had once worked at the same elementary school as Harris-Wiggins’s mother, Nancy. The two women were so close that Nancy was in the delivery room when Youngkin’s children were born and later was a fixture at the Youngkin home, where she babysat. But Youngkin did not know Nancy’s family—which is why he was surprised to learn his wife’s old friend was a party to the case. Harris-Wiggins remembers Youngkin coming over to say hello to her and her mother in the courtroom.

“I love your mom,” he said. “She was so helpful to me over the years.” Harris-Wiggins was dismayed by his nonchalant demeanor; it was as if they had just run into each other at the grocery store, not in a court of law battling for her family’s heritage. (“Just a total gaslighter,” she said later.) Her mother said nothing; she had been crushed when she learned it was Youngkin representing Capps. “Well, I love her too,” Harris-Wiggins finally replied.

Rodgers’s case hinged on the legal doctrine of adverse possession, in which a party can establish ownership even without clear title by proving that they have continuously used the land and paid taxes on it for a substantial period. Rodgers laid out the history of Petersburg Settlement, beginning with the freedwoman Priscilla Foster and her seven children, and then moving on to her heirs, so many of whom had gathered for the case that the courtroom resembled a family reunion. Rodgers called them to the stand one at a time, until he had established that the family or its hired caretakers had continuously occupied or tended the land for at least ninety years. “We’ve always known our history,” Harris-Wiggins said.

In January 2014 Judge Bryan ruled for the defendants. Capps still had a claim to much of Petersburg Settlement, but not the Foster heirs’ 63 acres, which would remain theirs. For Bryan, who retired in 2020, heirs’ property cases exemplify a conundrum judges often face—the tension between what is legal and what is right. “We see the law every day being used for an unjust purpose,” he said. “A judge has a responsibility in those matters,

because you’re supposed to consider equity as well as the law. Fortunately in my case the law was on the side of the people.” Capps took the loss personally. After the ruling, he began referring to the Foster tract as “Travis Bryan land,” a bit of spite that the judge considers “a badge of honor,” he said.

Harris-Wiggins and her family were elated. “We thought we had won,” she recalled. “We thought it was over.” But Capps was just getting started.

VI.

When Lawrence Smith heard that Harris-Wiggins had won her case, he knew that if he had been able to afford a lawyer, he could have proved his own family’s long history on the Anna Hackney tract and likely held onto the land.

On a sunny afternoon last spring, Lawrence and Brad took a drive from College Station toward Petersburg Settlement along Wellborn Road, once a country lane and now thoroughly developed on both sides with strip malls, apartment complexes, and new subdivisions. Along the way, Brad pointed out parcel after parcel that used to belong to acquaintances and relatives: the new apartments on land where his former employer R. B. Butler once ran cattle and the Koppe Bridge burger joint next to a plot once owned by another Black family named Smith. What was once a pasture now hosted a row of “Aggie Shacks,” the large multibedroom houses built as student rentals that have sprung up like mushrooms in old neighborhoods all around the A&M campus, which now boasts close to 75,000 students.

The story wasn’t a new one. “Black land ownership in Brazos County was under siege from day one,” said retired Texas A&M historian Dale Baum, an expert on the Brazos Valley in the nineteenth century. In 1867 freedmen began acquiring lots on the northern edge of Bryan, in an area known as Hall’s Town that has long since been incorporated into the city and today is Bryan’s predominantly Black neighborhood. It turned out that Hannibal Hall, a white man, had sold the freedmen properties that were encumbered by debts he had incurred or to which he had no lawful deed. As a result, some lost their land in Hall’s Town or were forced to buy it a second time from the lawful owner.

Baum wrote a book about the tragic story of a Bryan resident named Azeline Hearne, who briefly became perhaps the wealthiest freedwoman in the South after her former owner died in 1866 and unexpectedly bequeathed his entire estate, which included a large Robertson County cotton plantation, to the son he had fathered with her. When her son died, in 1868, she received the inheritance. By this time, Hearne was already a member of Brazos County’s small but vital Reconstruction-era Black middle class. But her new wealth was her downfall. Speculators filed bogus claims on the plantation, citing among other things old Spanish land grants that allegedly preempted her deed. She died penniless.

Wellborn Road eventually opened up into rolling green pasture, and entrances to new subdivisions began to appear on the left and right as Lawrence and Brad approached Millican. The tiny town has a violent chapter in its history, though few outside of Brazos County’s older generation of African Americans are aware of it. As the northern terminus of the Houston and Texas Central Railway, Millican on the eve of the Civil War was a bustling cotton-farming town of three thousand, more than a third of whom were enslaved. By 1868, however, a yellow fever epidemic and the extension of the railroad north to Bryan left a much smaller community, now mostly populated by freedmen. The white minority, many of whom were financially ruined by the war and Reconstruction, grew restive—and some grew murderous. A Northern soldier assigned to Millican described it as a “miserable cutthroat hole.”

That was the year the Ku Klux Klan came to town. A local Black pastor and Union army veteran named George Brooks had been helping freedmen in Millican register to vote. In retaliation, a gang of Klansmen marched through the Black part of town on June 7, firing their guns and terrorizing the population. Brooks responded by organizing an armed posse to drive them off. Rumors of a Black uprising brought a mob of whites on the train from nearby Bryan, and days of indiscriminate violence against Millican’s Black population ensued.

An accurate number of the dead was never tabulated, but newspaper reports from the time indicated it could have been as high as 150, which would make the Millican Massacre one of the worst incidents of racial violence in American history. Brooks was tortured and killed, his body discovered in the Brazos bottoms and identified only by the hand missing a finger he had previously lost. In the years to follow, the Brazos Valley would become infamous for lynchings, as whites reclaimed control of the region’s politics and economy.

For Lawrence, the story of the massacre has always been personal; he grew up attending the church that Brooks founded. Not far from Petersburg Settlement sits a new development called Millican Reserve. Its website has a distinctly Chip and Joanna Gaines look—the celebrity couple’s Waco headquarters is about a hundred miles upstream on the Brazos—with pages devoted to a farmers market and hike-and-bike trails and such an emphasis on lifestyle that it is difficult to find any direct reference on the site to what the “Reserve” actually is, i.e., a subdivision with palatial homes on enormous lots. If marketing is where memory goes to die, Millican is well on its way from “miserable cutthroat hole” to Magnolia Farm.

VII.

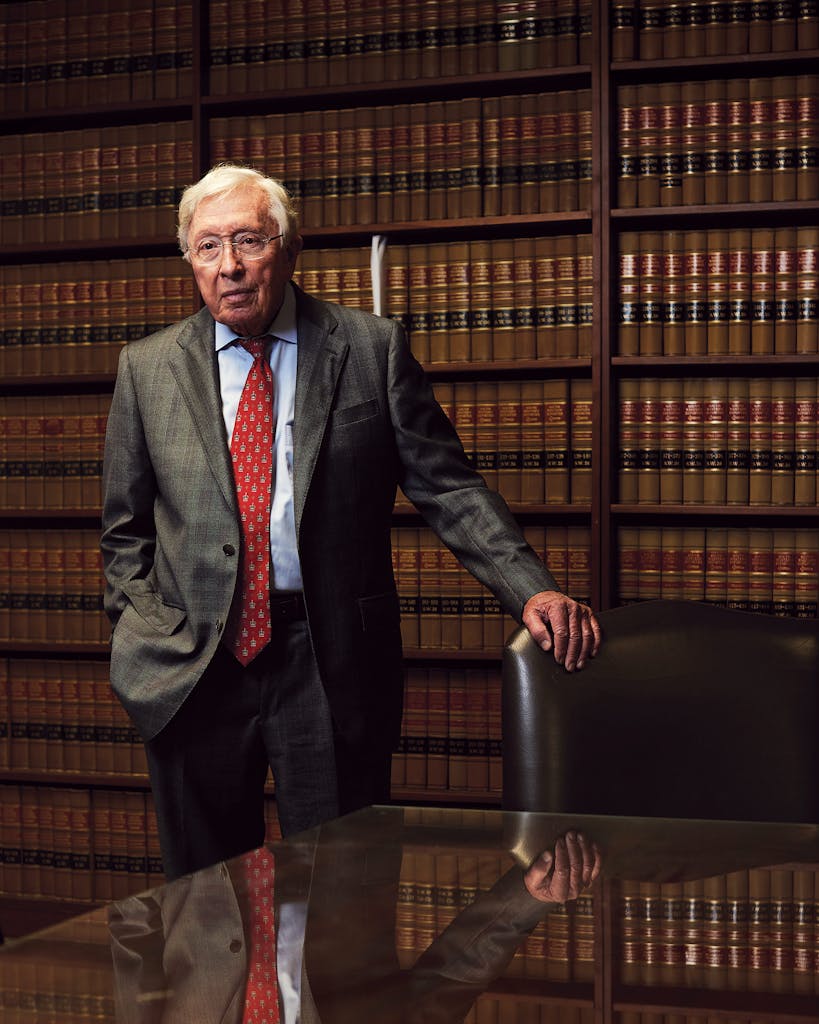

When Capps appealed Judge Bryan’s ruling in the Foster heirs case, Deborah Harris-Wiggins hired an appellate attorney from Houston named Karl Hoppess to defend their victory. Hoppess grew up in Bryan in a prominent family; his dad was a lawyer and part owner of one of the city’s two banks. His great-grandfather was the state land commissioner in the thirties and famously supported the University of Texas in a dispute with Texas A&M over land revenues for the pair’s competing endowments, a decision that subjected Hoppess’s family to (mostly) friendly ribbing for supporting the “teasips” over his hometown team.

Then 75 years of age, Hoppess, who has white hair and a grandfatherly smile, had long ago become something of a legend in his field. “Karl knows more real estate law than probably any lawyer in the state,” Steve Rodgers said. “When he goes into the Supreme Court to argue, the judges are just mesmerized.”

When Hoppess first laid eyes on Youngkin’s 2010 suit on behalf of Buetta and Rajena Scott, he was astounded. He wasn’t surprised to see that the ad litem attorney hadn’t objected to the suit’s leaps of logic or the testimony from the appraiser. It was far from the first time he’d encountered a case in which the ad litem, and the judge for that matter, did not seem well-versed enough in real estate law to intervene.

But there were other significant red flags. Of the dozens of heirs listed as defendants, only eight were served notice individually, even though records showed that Youngkin had correct addresses for at least eighteen of them—addresses to which he’d sent letters demanding compensation for Buetta and Rajena Scott’s tax payments. Hoppess also discovered that eight defendants had in fact made the payments requested, only to have them returned, accompanied by letters from Youngkin alleging that they were sent too late. Curiously, not one of those eight—each of whom seemed motivated to protect their interest in the land—was notified when the suit was filed. Despite having recently written to each of them personally, Youngkin told the court that he did not have their addresses and that he included their names in a list of defendants who had to be notified through the newspaper. To Hoppess, it all seemed calculated to keep the suit under the radar.

Rodgers told Hoppess something else alarming. It seemed that the only defendant who had shown up when the suit was heard—Billy Hines, the heir to the Alex Scott tract who had settled with Youngkin—never got what he was promised. Hines had kept his part of the deal, surrendering his interest in any of the land outside of his family’s long-held 45 acres. But Buetta and Rajena, instead of deeding their interest in his family’s property back to Hines, as the settlement required, had transferred it to Curtis Capps, along with their interest in all the other tracts they had acquired in the judgment.

Hines told Hoppess he had never received a deed from Youngkin. When Youngkin eventually submitted a deed to the county clerk’s office, the terms had changed. Capps had deeded back only Hines’s small undivided interest in the Alex Scott tract and kept the rest for himself. Youngkin had a letter in which Hines’s attorney, Emil Sargent, had approved this far different settlement. Sargent told Texas Monthly that he couldn’t account for the discrepancy but that “the agreement that was read in court was the agreement that we made.” Regardless, it didn’t matter; Texas case law had established that the terms Youngkin put into the court record could not be disregarded.

In January 2016 the Tenth Court of Appeals, in Waco, upheld Judge Bryan’s ruling, confirming the Foster heirs’ ownership of their tract. But Hoppess wasn’t done with the case. That spring, Hines and the other Alex Scott heirs hired him to pursue a fraud suit against Capps, Buetta, and Rajena. Hoppess had teamed up with an experienced Bryan attorney named Jay Goss, who knew Youngkin and Capps well. The pair eventually decided to add Youngkin as a defendant too. It was an unusual move—attorneys are not generally considered liable for misdeeds committed by their clients. In this case, however, Hoppess argued that Youngkin’s role in brokering the duplicitous settlement had placed him squarely in the middle of a conspiracy to defraud Hines. It raised the stakes considerably for Youngkin, who would now personally be liable for any judgment in the suit.

Hoppess opened a second line of attack on behalf of the Alex Scott heirs, asking a new judge to set aside Judge Langley’s 2010 ruling. If successful, this new filing, known as a bill of review, would remove Capps’s claim on the Alex Scott tract. But it had the potential to do much more; victory would undermine Capps’s claims on other portions of Petersburg Settlement, which could affect other cases, such as Lawrence Smith’s. The fraud and bill-of-review filings would also allow Hoppess to conduct discovery—obtaining records from Capps related to the suit—and to take depositions. It was a declaration of war.

Youngkin immediately sought to have himself removed as a defendant in the fraud case, but his luck at the courthouse seemed to have shifted. The trial judge ruled against him, as did the Tenth Court of Appeals, which found that Hines’s allegations against Youngkin were plausible. Youngkin appealed the ruling to the Supreme Court of Texas. After stalling for months, Youngkin and Capps finally turned over most of the discovery materials Hoppess had requested. Goss then flew to Oakland to depose Rajena Scott, in November 2017. The result was a rare inside view into how Youngkin and Capps do what they do.

Youngkin represented Rajena at the deposition; it was, as Goss would establish, the first time he had ever met his client in person. (Buetta did not testify; she by then had dementia, and Rajena, who was in her late sixties, was her caretaker.) Under questioning by Goss, Rajena admitted that she had never been to the property she had filed suit over. As one of dozens of known heirs, her mother’s undivided interest in the tract was tiny. Though she was born in Bryan, Rajena had been raised in California from an early age and had visited Texas only once, when she was a teenager. She was remarkably unfamiliar with the details of the litigation filed on her behalf.

It had all begun with a call from Youngkin. He told Rajena her mother was being sued by Brazos County for unpaid taxes for land that belonged to the family of Buetta’s deceased husband. Then he offered her a deal: if she and her mother would agree to hire Youngkin, he would file a Chapter 29 lawsuit on their behalf against the other heirs. Buetta and Rajena lived modestly and did not have the money to pay Youngkin or the $9,800 tax payment that the suit would require. That didn’t matter, Youngkin told them. His client, Curtis Capps, would put up the necessary funds if they agreed to deed over to Capps every acre they received as a result of any court judgment, for which they would be paid. Unable to file the Chapter 29 suit himself—since he was not an owner of the delinquent property—Capps had essentially hired Buetta and Rajena to do so on his behalf.

In his deposition, taken in December 2018, Capps said he had agreed to give them $3,000 for each acre they acquired through the suit. Yet the contract they signed with Youngkin didn’t actually specify how much they would get—that part was just an oral agreement. Rajena testified that she and her mother had received what Capps and Youngkin promised, but she never stated how much she understood that to be.

A list of payments Hoppess obtained during discovery revealed that Capps had given the pair only roughly $28,000 in total. The deeds he received were worth hundreds of thousands. (“They got bamboozled by Capps, just like everybody else,” Harris-Wiggins said later.) When the subject came up in Capps’s deposition, he was unapologetic. Goss asked if there were any other payments his team might have missed. “Possibly a minute amount here and there,” Capps replied, “when [Rajena] was calling and begging for some money to buy groceries.”

Capps also affected a lack of familiarity with the details of the lawsuit. Youngkin handled all of that, he told Goss. (“That’s what I pay him for; I’m going to do what he tells me to do,” Capps later told Texas Monthly.) Goss and Hoppess had noticed something peculiar in the list of payments Capps had submitted. There were payments to Buetta and Rajena, payments of court fees, payments for back taxes, payments to an appellate attorney—but no payments of attorney fees to Youngkin. Under questioning by Goss, Capps testified that the pair had never discussed Youngkin’s compensation for his work on the case, which by now had likely come to hundreds of hours—tens of thousands of dollars’ worth.

Clearly, after decades of working together, the two had an arrangement. It helped explain in part why Capps could afford to pursue litigation that lasted for years while many of his opponents could not—he didn’t have to pay his attorney until the case bore fruit. But Capps was vague about how exactly Youngkin would be compensated. He insisted that he and Youngkin had not agreed to split the title for the tracts in Petersburg Settlement or to divide the proceeds when the land was eventually resold. (Although appraisal district records reviewed by Texas Monthly suggest that they did share title to land they acquired in the eighties, in the early years of their partnership.) Capps’s evasiveness was understandable: if Youngkin benefited from the alleged fraud beyond his normal legal fees, he too might be liable.

In fact, one payment Capps had made suggested that Youngkin had benefited from the Petersburg Settlement scheme. Records provided in discovery revealed that Capps had given Youngkin $26,000. Capps told Goss the money was half of a bonus check he received when he leased the mineral rights to some of the Petersburg Settlement land he had acquired from Buetta and Rajena. Hoppess decided it was the smoking gun he needed to prove that Youngkin belonged in the fraud case. Unfortunately for Hoppess it had come too late—the state Supreme Court had already decided, in April 2018, that he couldn’t sue Youngkin.

Unless a lawyer can be shown to have benefited personally from a fraud perpetrated by his client, the justices ruled, his or her actions in court on behalf of a client could not expose them to liability. Hoppess believed that because he hadn’t been able to establish that fact in his Supreme Court brief, he’d let Youngkin wriggle free.

VIII.

As Hoppess and Goss made progress, Capps responded by taking the gloves off. In the fall of 2017, not long before Rajena’s deposition, Deborah Harris-Wiggins paid a visit to the family land. When she turned off the county road from which Petersburg Settlement could be reached and headed up the dirt lane that led to her property, she encountered a new gate blocking her way.

For generations her family had used the private road for access, just as her fellow owners had. But Capps had purchased the tract nearest the county road, which meant all the other landowners would have to cross his property to get to their own. Because there was no other way into Petersburg Settlement, Capps had effectively landlocked them. He placed “no trespassing” signs on the gate, along with a game camera, allowing him to record who came and went.

In response, Harris-Wiggins had private property signs of her own made, a few of which she gave to her then-husband Donnell to hang up when he and a friend went fishing in a pond on the Foster tract. Shortly after his visit, Donnell called her from jail; he and his friend had been picked up on a warrant. The charge was trespassing, and the complainant was Capps. Hoppess and Goss hired a criminal defense attorney who got the charges dismissed, but the next time Harris-Wiggins’s family visited the land, the gate was locked.

Hoppess went back to Judge Bryan’s court in the fall of 2018 and won an injunction against Capps’s denial of access and general harassment of Hoppess’s clients. Hoppess cut the lock off the gate himself, but within a year it was back on; Capps had appealed Bryan’s injunction to the Tenth Court of Appeals—the third time the panel had been asked to weigh in on this case—and the justices had ruled that Hoppess hadn’t sufficiently proved that his clients had a right to cross Capps’s property to reach their own. Hoppess went back to work on a brief that he thought would satisfy the court.

The case was now occupying far more of Hoppess’s time than he had ever anticipated, but the more he learned about how Capps and Youngkin operated, the more determined he was to pursue it to the end. By now almost everyone in Bryan’s tight-knit legal community had heard about the ongoing war over Petersburg Settlement. At a funeral for a friend in Bryan, Hoppess was approached by an old law partner of Bill Youngkin’s. “I want you to never quit on this one,” he said. “Don’t you ever let him off the hook.”

Then in May 2019 Hoppess got the breakthrough his team had been waiting years for. A judge ruled in his favor on the bill of review, finally setting aside the flawed 2010 verdict that had caused so much trouble for so many people. The new ruling rendered all the deeds Buetta and Rajena Scott received from the Chapter 29 suit invalid. Capps’s appeal was rejected by the Tenth Court of Appeals in the summer of 2020, and the original Chapter 29 suit was dismissed.

Since then, the situation has entered a stalemate of sorts. Slowed by the pandemic, Hoppess’s attempts to reopen the private road to his clients’ land have yet to bear fruit. There was no need to go to trial on the fraud case, as far as Hoppess was concerned; since Capps no longer had a claim on the Alex Scott tract, Billy Hines had in effect been made whole. For their part, Capps and Youngkin consider Capps’s deed for the Scott tract, along with the others he received from Buetta and Rajena, still good. (It’s possible yet more litigation will be required to settle the question.)

“I think their plan is to outlive me,” said Hoppess, who turned 85 last spring. “That’s how they think they are going to win.”

IX.

Curtis Capps likes to conduct business at Bill Youngkin’s workplace, which these days is in an old-fashioned storefront with painted windows in downtown Bryan. That’s where he gave Texas Monthly an hour-and-a-half-long interview in August. Youngkin did not attend because he was in the hospital undergoing a heart procedure. Capps sat in the small, modestly appointed space festooned with memorabilia from Texas A&M, where the two men met more than fifty years ago. Leaning against one wall was an enlarged map of Petersburg Settlement, the land that had once supported the children of a former slave and had now become Capps’s great white whale.

“Sounds like you’re trying to paint me a picture of a bad guy, who’s got a lot of money and just runs over everybody,” he said. To him, the acquisition of heirs’ property was not a moral issue; it was just good business.

“Typically that’s where you can get a better buy on a piece of land,” he explained. “I buy stuff where the title is messed up and try to cure that title to the point that it can be resold, hopefully for a profit. . . . It’s not wrong, not at all.” Capps insisted that he didn’t set out to target Black landowners, though he conceded it had often worked out that way in practice. “It’s because they don’t do anything to maintain their property. They just let it go.”

Capps couldn’t remember how many heirs’ cases he and Youngkin had done over the years (“Oh gosh, I couldn’t even guess to give you a number”), but he was sure he’d never had one blow up on him like Petersburg Settlement did. When it came to discussing the details of the fight, Capps was by turns defensive and garrulous. He suggested the Chapter 29 suit that started it all wasn’t his idea (“It wasn’t me!”) and declined to say exactly why he chose Buetta and Rajena Scott to file it. (“Just lucky I guess.”) He said Youngkin would never have conspired to keep heirs from being notified about the case. (“He’s a damn liar, whoever said that.”) When it came to the question of whether or not he had paid Buetta and Rajena what he promised, he was no more interested in discussing the subject than he had been in his deposition with Jay Goss. (“I don’t recall.” “If I paid twenty-five [thousand], I probably paid too much.”)

Capps brought along his appellate attorney, Ty Clevenger, a 53-year-old former A&M student body president who has made a name for himself as something of a legal bomb thrower. (He accused Karl Hoppess of “dirty lawyering” in an appellate brief and over the years has filed bar grievances against the likes of former U.S. attorney general Loretta Lynch, former FBI director James Comey, and Hillary Clinton.) It was Hoppess who was stalling any resolution to the dispute, Clevenger insisted, not Capps. “Karl Hoppess and Jay Goss will concoct any half-baked lawsuit they can think of and go file it to jam this up,” he said. With respect to the fraud case, Clevenger said, “If Billy Hines wanted to sue somebody, he should have sued his own attorney.”

If Petersburg Settlement began as a brass ring for Capps, by now he seemed to think of it as an albatross. By his own accounting, he has invested more than $400,000 in the fight, mostly for appellate fees, back taxes, and settlements with various heirs. He still owns a number of parcels (such as the Anna Hackney tract) that he acquired through judgments or purchases from heirs, but without possessing the entirety of Petersburg Settlement, their value is limited. Still, he couldn’t help sounding a boastful note about the deal he almost landed. “There’s nothing comparable in that part of the world that’s for sale like that,” he said. “If there’s anything like that, I’m not aware of it.”

He still insisted that his title work—his reading of the puzzle of Petersburg Settlement’s ownership history—was correct. But to him the ongoing dispute wasn’t really about that anymore. “In my mind, right or wrong, it’s nothing to do with title,” he said. He hinted darkly at “ulterior motives” at work—in the court rulings against him, in Hoppess’s age-defying indefatigability, in the organization of the Black community against his efforts. “If you find out let me know, because everything that was done by my side was done by the facts and by the law.”

Capps’s purchasing of undivided interests and use of forced partitions, through which he acquired entire tracts, was indeed legal. And the courts have affirmed his right to lock Deborah Harris-Wiggins and her family, along with other Petersburg heirs, out of their land. But those who say their property was wrongfully taken from them are quick to question the legality of some of the tactics employed by Capps and Youngkin, such as the failure to notify all known heirs and the unfulfilled terms of the Billy Hines settlement.

In a subsequent interview, Youngkin denied defrauding Hines or trying to hide lawsuits from heirs who should have been notified by letter. He cast his work on Petersburg Settlement and other heirs’ property cases as a useful service—at least to those who didn’t lose their interests to his clients. “When you have a piece of property that goes for a hundred and twenty-five years and nothing is done, and it’s landlocked property, it is basically worthless unless somebody comes in and spends the time, the effort, and the money to clean it up and clear [the title] up,” he said. “I think what happened here was a lot of hard work and an awful good business decision.”

Hoppess, who has invested a considerable amount of his own money helping Harris-Wiggins and her family pay legal fees, loves his work assisting in their crusade. “There are too many that have been abused,” he said of Black landowners in the Brazos Valley. “You have to understand that it didn’t end in 1865. I can’t tell you why it didn’t end, but it didn’t. It just keeps going.” He’s inspired by the grit of Harris-Wiggins and her relatives. “It’s a group of highly educated women who got tired of being pushed around,” he said. “Capps got ahold of them, and he got the hell he never expected.”

Harris-Wiggins, for her part, calls Hoppess “our savior” and “our rock.” The family initially paid Hoppess and Goss by collecting a levy on each of the heirs—64 at last count—who had joined the suit. But the proliferation of cases and the lengthy appellate process have meant the bill has now grown so large that the heirs will have to pay their attorneys with the only resource they have available—a percentage of the land itself. “Some of our family is ready to give up,” Harris-Wiggins said. “They say, ‘It’s been ten years, we can’t do this anymore, nothing is happening.’ ”

Several heirs, including Harris-Wiggins’s aunt Nettie, who first spotted the lawsuit in the Bryan–College Station Eagle, have died as the litigation has dragged on. In Harris-Wiggins’s mind, the fight is for her mother, who is now the last living sibling of her generation. Barred from their land by Capps’s gate, the family has found new locations to gather for the past several years of annual reunions. But it is not the same, Harris-Wiggins said. “Everything in this world can be replaced except the land.”

In July of this year, Youngkin approached Hoppess with an unexpected offer—a cash settlement from Capps in exchange for all the land held by Hoppess’s clients. To Hoppess, the offer, which Harris-Wiggins and her family rejected, was an admission from his longtime adversary that he was never going to sue his way to ownership of Petersburg Settlement. “I think he has finally given up on the idea,” he said. Just how the Petersburg Settlement saga would end, however, he couldn’t say.

Capps’s efforts elsewhere in the Brazos Valley may have been slowed by the heirs’ property reform Senator Royce West pushed through the state legislature in 2017. Similar reforms, all based on model legislation created by Thomas Mitchell, then a Texas A&M law professor, have now been passed in 23 states. Mitchell, who won a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” for his work, has arguably done more than any other person to push heirs’ property into the spotlight. Now at Boston College, Mitchell told Texas Monthly it’s still too early to assess the reform’s effectiveness in Texas. Even if heirs want to take advantage of the new law, he said, Texas lacks the kind of robust nonprofit legal services for heirs’ property owners that have made a difference in other Southern states, particularly Georgia and South Carolina.

Lawrence Smith testified at a hearing for West’s bill, after an advocacy group in Austin learned about what had happened with his family’s land. But the new law will have no effect on his case, which predated its passage. The ruling on the bill of review left Lawrence’s land in legal limbo. Capps’s suit against the Anna Hackney heirs was predicated on the Petersburg Settlement deeds he had obtained from Buetta and Rajena in 2010, and those deeds may now be worthless. But Capps can still point to the 2013 judgment awarding him the Anna Hackney tract, which has yet to be contested by Lawrence or his fellow heirs.

Even the appraisal district, which had transferred the land to Capps’s name in 2017, seemed at a loss about its legal status. After an inquiry from Texas Monthly, officials put the tract back in Lawrence’s family’s name, and he received the property tax bill as he always had before. The district’s official maps, meanwhile, still show Capps as the owner.

Such confusion redounds to Capps’s benefit. Realtors Lawrence has spoken to have declined to represent him because of the cloud on his title. Lawrence put his energy into a petition, collecting signatures from others who’d like an official review of all heirs’ property suits that have come before Brazos County courts. His list is now up to more than one hundred names. “I’m trying to get a story out there big enough to where some rich person up the ladder is gonna see it and do something about this,” he said.

X.

Though no grave marker has been found, Pastor George Brooks is rumored to have been buried near a sycamore tree behind his church in Millican, the same church Lawrence attended as a child. Lawrence’s father purchased the lot when the church closed in 1968, and Lawrence still owns it, though the church building is long gone.

Amy Earhart, an associate professor at Texas A&M who teaches African American literature, is working to get a historical marker erected on the site to memorialize the Millican Massacre. Bryan is a town obsessed with history—from Stephen F. Austin’s “Old 300” colonists who settled the area to the Camino Real, the Spanish trade route that passed just north of town. But few seem interested in this story. “This history is contained within the Black community,” she said. “It’s largely unknown in the white community.”

In the process of applying for the marker, Lawrence discovered that the official map maintained by the appraisal district does not show the half-acre lot where the church once stood, even though he has the deed his father procured for the land. When Lawrence tried to straighten out the mistake, the appraisal district told him, in effect, that no church ever existed on that site.

“It’s like we’re invisible,” his nephew Brad said.

Curtis Capps seemed to agree with this assessment, at least in one instance. After he acquired his stake in Petersburg Settlement, he discovered the local power company had negotiated unfavorable easement terms with the previous owners, treating them, as he put it, “differently from their neighboring landowners who were white.” He gave notice that a white man now owned the property in the best way he knew how—he had Bill Youngkin sue Bryan Texas Utilities.

One day last summer, Lawrence spotted Capps at an H-E-B in Bryan. They exchanged a nod in passing, but Lawrence didn’t want to provoke a confrontation. Then he thought better of it.

“Hey, let me ask you something,” he said, turning back to Capps. “How am I supposed to get to my land?” Lawrence could see by Capps’s reaction that he hadn’t recognized him.

“And what land is that?” Capps asked.

“Petersburg Settlement,” he said. “The Anna Hackney tract.”

“Anna Hackney?” Capps replied. “Oh, I own all of that.”

Correction: This article originally misstated Lawrence Smith’s age in 2012.

This article appeared in the November 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Dispossessed.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Longreads

- College Station

- Bryan

You must be logged in to post a comment Login