As University of Texas freshmen attended their first lectures last week, figuring out how to get to class and where to grab their grub, the atmosphere on campus remained raw and in some quarters riven over how to address a troubling institutional history. After the summer of 2020, when the murder of George Floyd spurred students and other members of the UT community to press university officials to do more to confront racist chapters in the school’s history, administrators agreed to rename some buildings and erect new monuments on campus to honor the contributions of Black UT alumni, and pledged to create a more inclusive environment—even as they stopped short of scotching a fight song with racist roots.

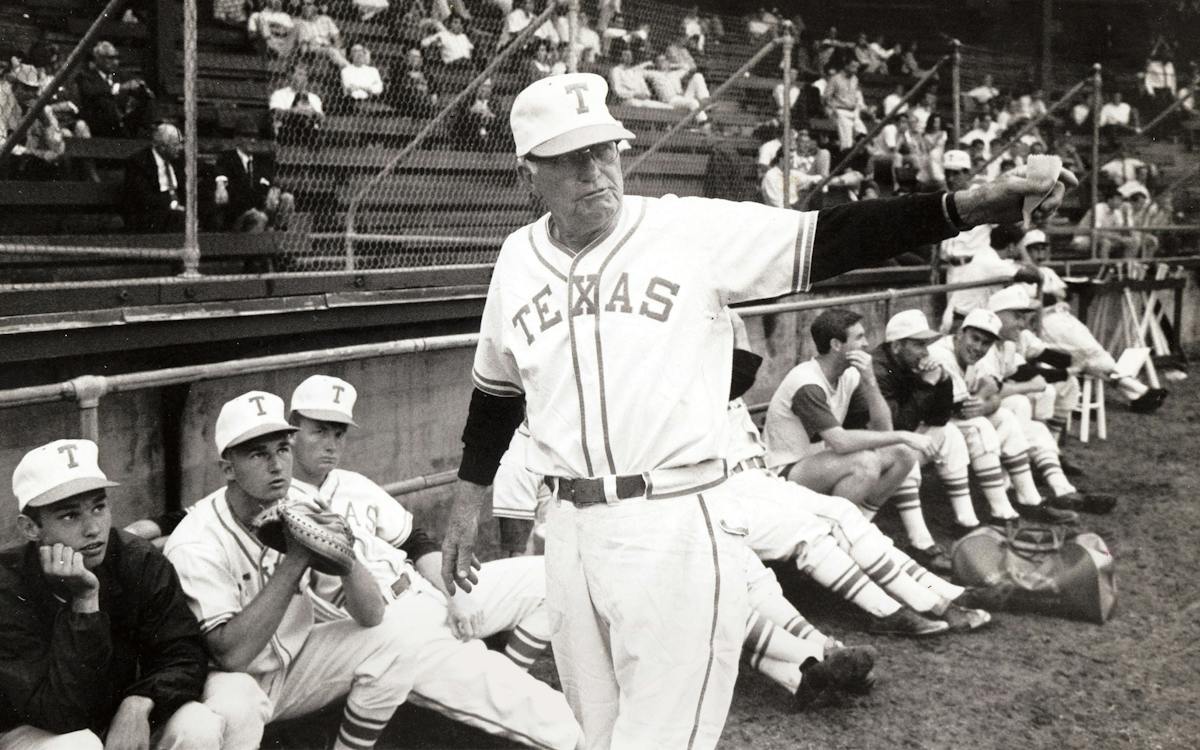

One structure left untouched in that round of reform was baseball stadium Disch-Falk Field, named in part for Bibb Falk. Born in Austin around the turn of the twentieth century, Falk starred as a pitcher on the UT team after World War I. Following a twelve-year career in the majors, where he played left field for the Chicago White Sox and the Cleveland Indians, Falk returned to UT in 1940 to coach the Longhorn squad. By the time he retired in 1967, his teams had won twenty conference titles and two national championships.

Those teams included no Black players.

According to an internal memo from 1959, obtained by Texas Monthly, Falk, along with other famed UT coaches, opposed integrating the school’s sports programs—a full five years after the U.S. Supreme Court declared school segregation unconstitutional in its Brown v. Board of Education decision. Falk “definitely doesn’t want any Negro players,” dean of student services H.Y. McCown wrote to university president Logan Wilson that November. “He says they will not fit into his set-up.”

The memo, stamped “Confidential,” is part of a folder labeled “Negro Students” in the UT Dean of Students Records—an archive that now occupies 42 linear feet of library boxes at the school’s Briscoe Center for American History.

Influenced by the fear of budget cuts from segregationist state lawmakers, by donors who threatened to withhold money if they saw Black athletes representing the university on the field, and by their own attitudes, high-ranking UT officials did what they could to stymie integration. Even as the school was forced to admit Black students, administrators preserved segregated dorms, prevented Black students from acting alongside white classmates in undergraduate theater productions, and blocked Black students from participating in varsity sports.

“The notion that he was on the wrong side of history and opposed desegregation wouldn’t have surprised me at all, given the climate of the day,” said Kirk Bohls, a longtime sports columnist at the Austin American-Statesman who has interviewed Falk. “He was a crusty old redneck, a tough bird who was a product of the times, sometimes unfortunately. He was often described as a world-class cusser and tough as nails, and sadly declined to break down any racial barriers.” The memo is a “smoking gun kind of document—but it’s also not that surprising,” added Edmund T. Gordon, an associate professor of African and African Diaspora Studies who leads racial geography tours on campus.

In the memo, McCown describes how Falk, football coach Darrell Royal, basketball coach Harold Bradley, and track and field coach Clyde Littlefield felt, at the time, about the prospect of coaching mixed-race rosters. Less than a month earlier, student association president Frank Cooksey had sent a letter to UT administrators urging them to integrate the school’s sports programs. “Last Saturday a Negro football player from the University of Oklahoma made 135 yards rushing against the University of Texas football team,” Cooksey, who later became mayor of Austin, wrote. “I dare say that the coaches on the Longhorn staff would be quite ready to accept the services of any one who could play football as well as Mr. Prentice Gautt did on Saturday afternoon.”

Perhaps not. The memo shows that Falk and the other famed Longhorns coaches, whose names grace university arenas and sporting events, preferred to remain far behind the curve of racial progress. According to McCown, Royal, who had previously coached an integrated squad at the University of Washington, said having Black athletes on the UT team would “create problems.”

“White players particularly resented Negro boys coming in their room and lounging on their beds,” the memo continues. “Darrell was quite pronounced in not wanting any Negroes on his team until other Southwest Conference teams admit them and until the housing problem is solved or conditions change.” Time and again, throughout the late fifties and sixties, Royal and coaches at other Southwest Conference schools argued that they preferred to postpone integrating their football teams until others in the conference did.

It was an effective stalling tactic—and it turned out to be disingenuous: even after Southern Methodist University made Jerry LeVias the conference’s first Black scholarship football player in 1966, it took another four years before Julius Whittier broke the color barrier and joined the UT football team. (Royal’s record on race takes a small book to parse—he was still coach when the team integrated and some Black players credit him with installing a mentorship program with Black professionals in Austin; Royal, who also served as athletic director, stated that LBJ, with whom the coach developed a close friendship, made him rethink how he could use his position to improve equality.)

“All coaches expressed the same concern over housing and recruitment,” McCown wrote. “Both at home and on the road, we would have housing problems. The coaches wouldn’t want to have their players housed in different places. On the other hand, it would be unthinkable to assign a Negro and white student as roommates. If we were the only Southwest Conference team with Negroes it would be ruinous in recruiting. We would be labelled Negro lovers and competing coaches would tell a prospect: ‘If you go to Texas, you will have to room with a Negro.’ No East Texas boy would come here.” UT football didn’t recruit its first Black scholarship player for another eleven years. And no Black athlete received a baseball scholarship to UT until 1977, a decade after Falk had retired as coach.

Falk died in Austin in 1989 and was posthumously named to the College Baseball Hall of Fame. Last year, the university baseball team honored Andre Robertson, the second baseman whose steady bat and sterling defensive play made him the Longhorns’ first Black scholarship player. (Robertson has joked that he opted for baseball instead of football after he saw Earl Campbell in the weight room.) Robertson played five seasons with the New York Yankees, threw out the first pitch at UT’s 2020 alumni game, and was later recognized on the Longhorn Network’s “History Makers” series.

There appears to be no discussion about removing Falk’s name from the baseball stadium. Asked via email whether UT president Jay Hartzell thinks the coach’s name should come off the building, university spokesman J.B. Bird did not offer a response.

Some educators have argued against applying today’s values to figures like Royal and Falk, preferring instead to preserve the names of problematic figures on buildings and add explanations that describe their shortcomings and accomplishments. In the summer of 2020, in an open letter to the UT community, Hartzell explained his decision to keep the names on some campus structures while adding plaques that would give context. Hartzell cited “the opportunities we have to use the stories surrounding these individuals and symbols to educate, to learn, and ultimately, to move us closer together as a community.”

Gordon, the UT professor, said that despite the renaming of a building last year that had honored a math professor who refused to teach Black students, UT’s campus remains “chock-full” of buildings that honor Confederate figures and segregationists. “The place is replete with this kind of symbology,” he said. “One of the things the UT president has said is there needs to be a robust process of contextualization.” For example, Gordon said, at Darrell K Royal–Texas Memorial Stadium, there should be an acknowledgement that Royal, “among his many fabulous traits, whatever those may be, was involved in the maintenance of racial segregation for athletics after the university itself had desegregated.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login