States

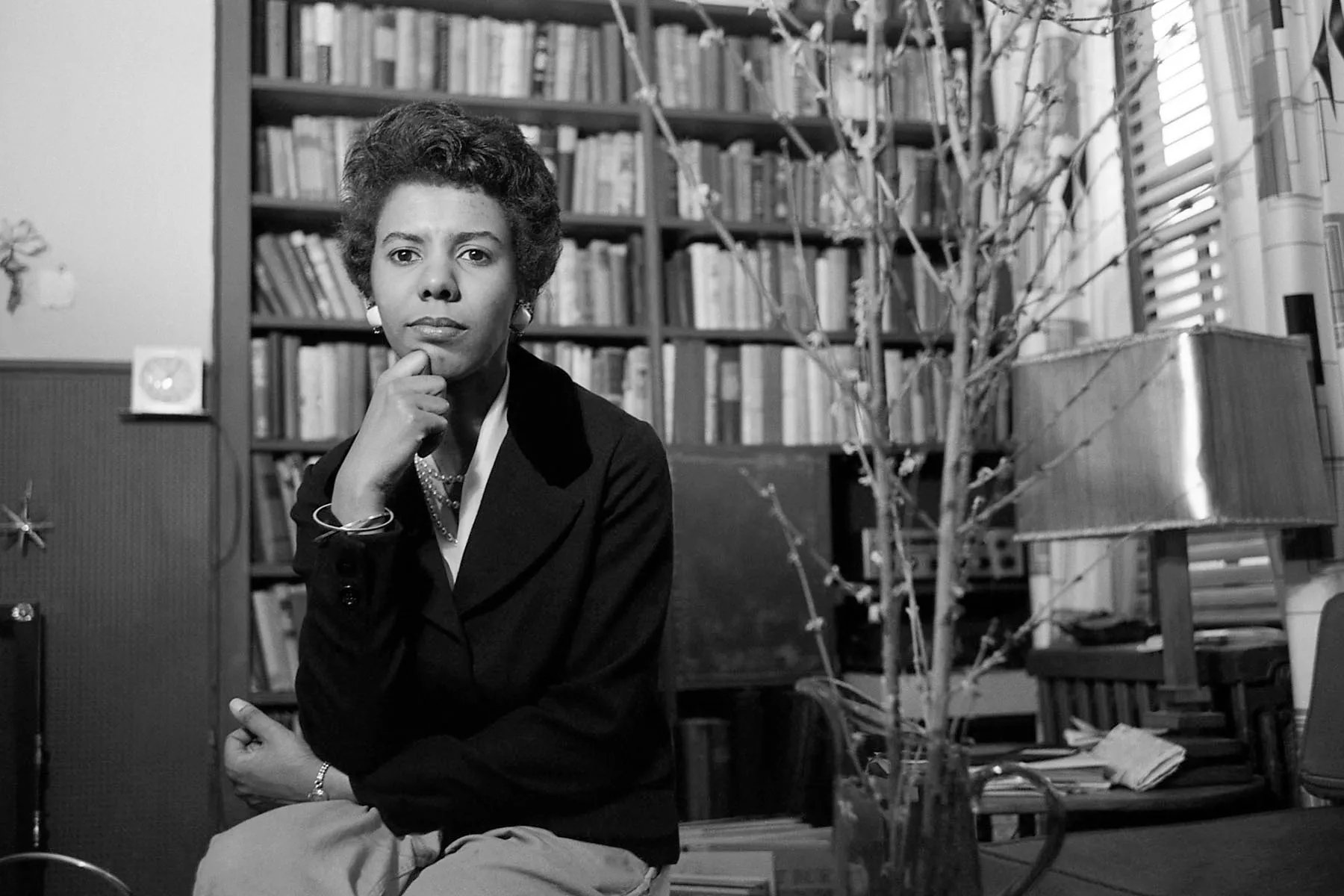

Lorraine Hansberry’s Family Seeks Reparations For Land Seized By Chicago’s Racist Policies

Chicago’s Racist Policies:

“A Raisin in the Sun” arched on Broadway in 1959, depicting a packed Chicago apartment where bigotry crushed Black families’ ambitions. Lorraine Hansberry was the first Black woman to write a Broadway play. However, underlying this theatrical milestone was a more profound struggle that reflected racism in her life and the environment that fuelled her celebrated work.

Lorraine’s “A Raisin in the Sun” follows the Youngers, a five-person family living in a small kitchenette apartment in Chicago’s Black Belt. Racial injustice stifles their hopes that a $10,000 life insurance premium from their dead dad may improve their living conditions.

While the drama was making history on Broadway, Lorraine and five family members fought a separate struggle. They sued Chicago, then-Mayor Richard J. Daley, and other authorities for $1 million 1958. They claimed that the city’s “unreasonable and capricious mass inspections” and state power abuse had taken their family’s property. Unfortunately, the result of this landmark 1958 case is unknown.

The Call For Reparations And Legacy Restoration

Today, Lorraine’s sister Mamie Hansberry and her grandniece Taye Hansberry ardently advocate for restitution. Beyond financial compensation for lost possessions, they want to reclaim their patriarch’s heritage. Lorraine’s father, Carl Hansberry Sr., worked hard to accumulate a fortune so his daughter could follow her creative goals in New York. He left a prosperous real estate company when he died in 1946. However, urban renewal and eminent domain regulations, which they think were racially biased, undermined their family’s riches in later decades.

Taye Hansberry effectively emphasizes self-reliance: “Nothing was provided. It took effort. Do we not get the American dream like everyone else?” The charity “Where is My Land.” supports the Hansberry family’s fight for justice. The nonprofit, founded by Kavon Ward, returned Bruce’s Beach to the Bruce family in Manhattan Beach, California. In the 1920s, municipal authorities falsely condemned and seized the Black family’s land.

A Growing National Movement For Reparations

An increasing number of Americans are calling for reparations for the Hansberry family. Evanston, Illinois, was the first U.S. city to provide housing restitution to Black people. A $5 million lump-sum payout is being considered in San Francisco. Task forces in Memphis, Boston, and New York are exploring how reparations may repair the harm caused by slavery and its legacy.

The Hansberrys’ reparations argument focuses on systemic racism’s effects on exclusionary measures during Chicago’s urban reconstruction. By 1935, when Black communities were overflowing from the Great Migration, Carl Hansberry Sr. owned at least ten homes on Chicago’s South Side.

Millions of Black Americans left the South for northern cities like Chicago during the Great Migration to find better living conditions, jobs, and safety from racial violence. Carl Hansberry Sr., a Mississippi-born real estate dealer, saw the housing crisis, racial segregation, and restrictive covenants throughout this period.

The Hansberry family’s campaign for reparations isn’t just about money; it’s about rewriting their family’s history and correcting the inaccurate portrayal of Carl Hansberry Sr. as a slumlord.

He fought harsh rules and racial discrimination in court as a civil rights activist. His family wants to honor Carl Hansberry Sr.’s commitment to economic development and fair opportunity for Black people while fighting racial injustices.

Read Also: Most Black Americans Perceive Racist Or Negative Depictions In News Media

The Roots Of Urban Renewal And Displacement

A nationwide urban redevelopment effort eroded the Hansberry family’s riches, not only in Chicago. Urban renewal was intended to rebuild decaying urban neighborhoods, but it had far-reaching effects on Black communities nationwide.

The 1954 Federal Housing Act mandated historical preservation, building code enforcement, and family relocation, setting the groundwork for urban revitalization. The problem was that building code enforcement routinely levied five-figure penalties. Hansberry paid $22,122 in fines for 12 properties in 1960. Bank loans for repair costs were difficult, requiring households to pay for them.

The Hansberry family faced 42 city-filed municipal court proceedings while renovating and revitalizing houses. Critics said urban regeneration was a deceptive word since it didn’t improve living circumstances for the individuals it displaced. However, many Black families were marginalized and forced into public housing while their neighborhoods were destroyed.

Challenges Faced By Families Amid Urban Renewal

Chicago practiced “Negro removal.” after Carl Hansberry Sr.’s 1946 death. A wave of municipal and federal laws displaced 50,000 households and 18,000 people between 1948 and 1963.

Chicago pioneered ideas and techniques that were ultimately accepted into federal law, establishing the countrywide urban regeneration program, according to historian Arnold Hirsch. This operation allowed the city to use eminent domain to take homes, demolish and eliminate slums, and relocate impacted residents. The Hansberry family’s experiences show how this harsh urban renewal program affected them.

However, these rules affected more than just the Hansberry family. Many Chicago Black families faced similar issues. Racism forced millions of Black Chicagoans into the Black Belt, a small region of the city. They couldn’t purchase or rent outside this region and had to pay higher rates for inferior property.

During the Great Migration, many families moved to Chicago for improved living circumstances but faced discrimination, redlining, housing segregation, and other systematic racism. Racially discriminatory legislation hindered their pursuit of the American ideal.

Carl Hansberry Sr.’s Legacy Of Advocacy And Resistance

Carl Hansberry Sr.’s impact goes beyond real estate entrepreneurship. He tirelessly opposed discriminatory laws and regulations as a civil rights activist. In 1937, he bought a property in Woodlawn, a primarily White area. An angry crowd gathered outside the Hansberry residence to oppose the transfer. Collective opposition led to a Supreme Court lawsuit.

This case reached the Supreme Court, where the Hansberry family won on a technicality. Despite not explicitly challenging racially discriminatory covenants, it invalidated the Woodlawn covenant, allowing Black Chicagoans to develop eastward. According to a 1940 Chicago Defender story, this decision gave them 500 more dwellings.

Carl Hansberry Sr. fought racial discrimination as well as limited housing. In 1938, he sued the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway for charging African Americans first-class tickets while sending them to third-class vehicles. His efforts highlighted Black traveler prejudice, even though the lawsuit was dismissed. Hansberry Sr. wrote a “Know Your Rights” brochure to inform Black travelers.

Carl Hansberry Sr. advanced Black rights and empowerment via litigation, businesses, and economic activities. His family is resolved to honor his legacy as a fiery advocate and businessman as they fight racial injustices and seek restitution.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login